3 photos

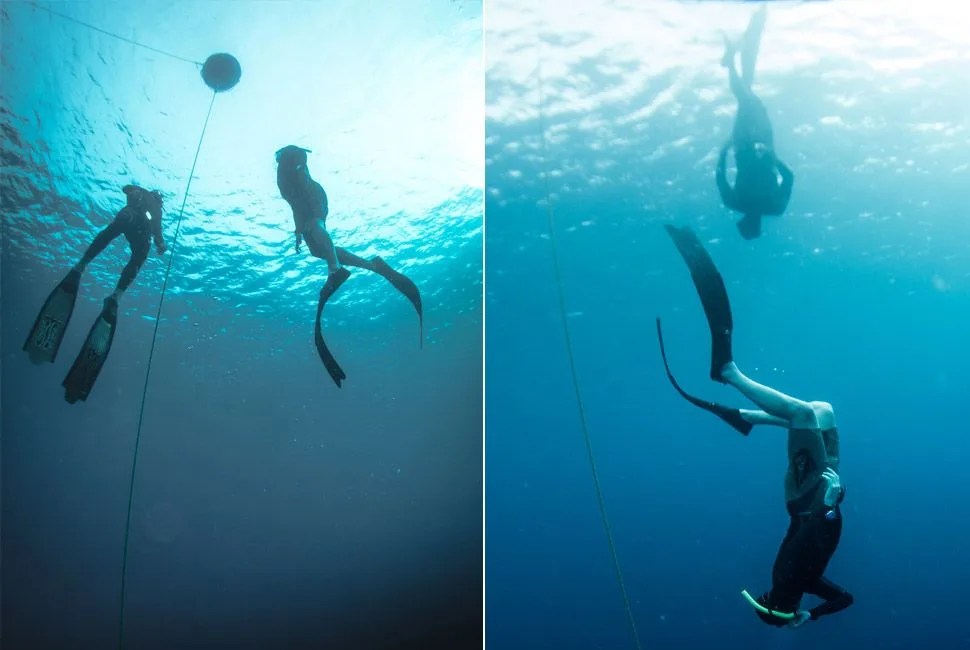

The pain in my right ear was excruciating. Another foot deeper and I was certain my eardrum would rupture. I shook my head and flipped upright, gave a single kick and felt myself rise, slowly at first. The pain subsided as the water pressure decreased, and I was able to enjoy the serenity of the scene: an endless canvas of blue sliced in two by the yellow rope right in front of my mask. Then, out of nowhere, a man appeared, his eyes wide, fingers looped in the universal diver’s “OK?” symbol. I nodded and pointed to my troubled ear and continued to kick, my speed increasing as my lungs re-inflated and my buoyancy increased. Now my diaphragm started to convulse, an autonomic response indicating I needed to breathe. I was prepared for this and relaxed through the sensation, allowing physics to do its work. A few moments later, I broke the surface, exhaled sharply and sucked in a breath. Across the red safety buoy, Carlos also broke the surface and, hardly breathless — as if he’d been snorkeling in a pool — said, “How was that?”

This was my fourth trip to Bonaire, an island in the southern Caribbean. I hadn’t returned for its starkly arid interior or historical Dutch town, nor for the iguana stew, but for the diving. Indeed, Bonaire is perhaps the finest place in the world for underwater sport, a fact reinforced by the planeloads of divers that land here daily from Europe and the Americas. Every battered pickup truck on the road has a license plate that reads “Diver’s Paradise”.

Most of the people who come to Bonaire are SCUBA divers, hauling heavy bags of gear—buoyancy vests and regulators. But on this visit, I decided to try something different: freediving. No tanks, just a breath of air. I wanted to experience the transcendent silence and freedom freedivers talk about. And though the minimalist form of diving has been practiced by humans for centuries and isn’t a complicated sport, I wanted some help. The best man to learn freediving from is in Bonaire, and I was about to get a one-on-one lesson from him.

No tanks. Just a breath of air.

That would be Carlos Coste, a professional freediver who’s set numerous world records in several of the arcane disciplines of this niche sport. He was the first person to break the 100-meter mark in Free Immersion (no propulsion, only pulling on a rope) and has held world titles and depth records in the Variable Weight and Constant Weight disciplines. In 2010, he swam 150 meters through Mexico’s Dos Ojos cenote, a flooded cave, setting a world record for the longest underwater swim on one breath in open water. If you don’t recognize Coste from his freediving accomplishments, he’s also a face for the ORIS watch company, who has honored him with three special edition dive watches since 2006. Though he still competes (he recently set the North American record for Constant Weight with a dive to 61 meters), Coste has recently set up a training center in Bonaire to impart some of his skills to anyone interested, from vacation snorkelers to aspiring competitors.

Coste greeted me at his home in a quiet gated community near Bonaire’s only airport. With his imposing height, close-cropped hair and chiseled physique, he would be intimidating if he wasn’t such a nice guy with a quick smile. He led me through the house to a breezy outdoor veranda, where he spread out two mats and proceeded to walk me through some basic yoga postures and breathing exercises to limber up my body and my lungs. While I’ve never been a fan of yoga, it has natural ties to freediving; success in the latter depends largely on relaxation, flexibility and extremely full lungs. Coste taught me the importance of “belly breathing”, filling the lungs first from the diaphragm and then the chest to maximize the capacity. Though it’s not the way most people breathe after infancy, once I learned the technique, I was surprised at how much air I was able to suck in.