19 photos

We left Geneva early, before sunrise, and the two-hour ride was serene, the only sounds the hiss of the tires on wet pavement and the muted hum of the Mercedes V8. The views out the window were breathtaking: a fresh dusting of snow coated the pine forests and steep hillsides we whisked past. Our destination was the tiny Alpine hamlet of Villeret, a town of 1,000 people nestled in the Jura mountains. As we entered the village, the big car pulled to a stop in front of a nondescript building on the roadside. This was the historic Minerva watch manufacture, now part of Montblanc, a brand more often associated with writing instruments than those that keep time. Stepping into the building was like stepping back in time to an era when small factories in these isolated mountain towns made a few watches a year.

MORE TIMEKEEPING PHOTO ESSAYS Live From Geneva: SIHH 2014 | Inside the Hamilton Watch Factory, 1936 | Sailing with Officine Panerai

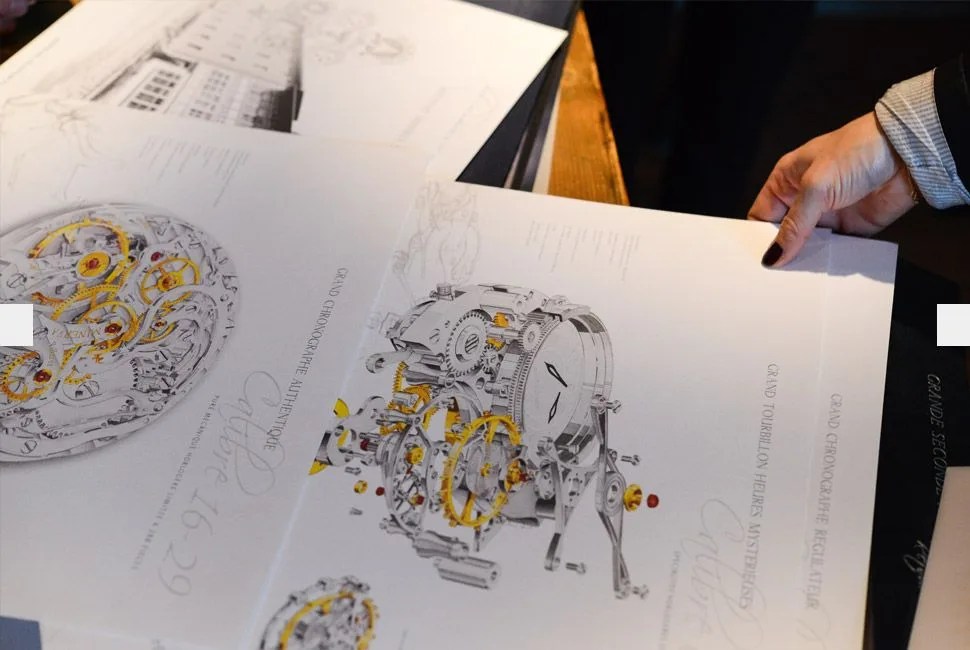

The history of Minerva — continuously in business since 1858 — is one of the longest in watchmaking. While the company name is not well known to most, among watch enthusiasts it is spoken of with reverence. It was once one of the preeminent builders of stopwatches and chronographs, under its own name and as a provider of movements to other, more prestigious brands. Minerva’s revolutionary 1/100th of a second stopwatch and split seconds functionality helped make it the choice as timekeeper for the 1936 Olympic Winter Games in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, and its chronographs were used by militaries on both sides of World War II. The movements were easily identified by their Y-shaped chronograph bridge and telltale arrow decoration as well as their smooth column-wheel-actuated functioning. With the advent of the so-called “Quartz Crisis” in the 1970s, Minerva fell into irrelevance and near collapse.

Montblanc started selling watches in the 1990s. The brand was already known for its leather goods and its precision writing instruments and wanted to leverage that reputation for craftsmanship in timepieces. In 2001 it bought the Minerva name and factory — and also gained newfound respect as the steward of a storied brand. Montblanc’s taken great care of the manufacture ever since.

This is a place of smells — lubricating oils, chemicals and that familiar scent of an old house, musty but comforting.

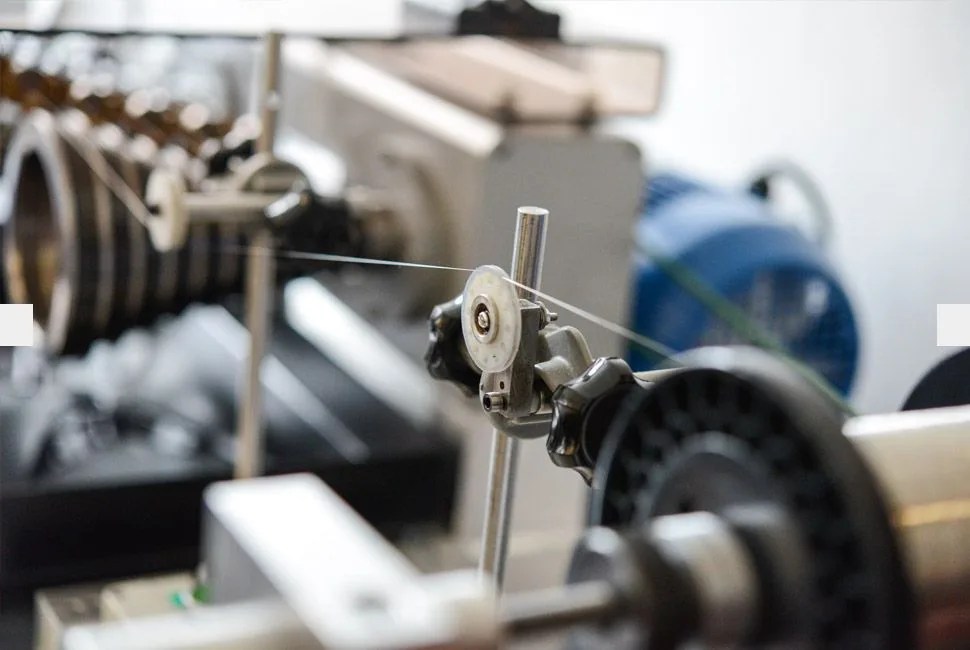

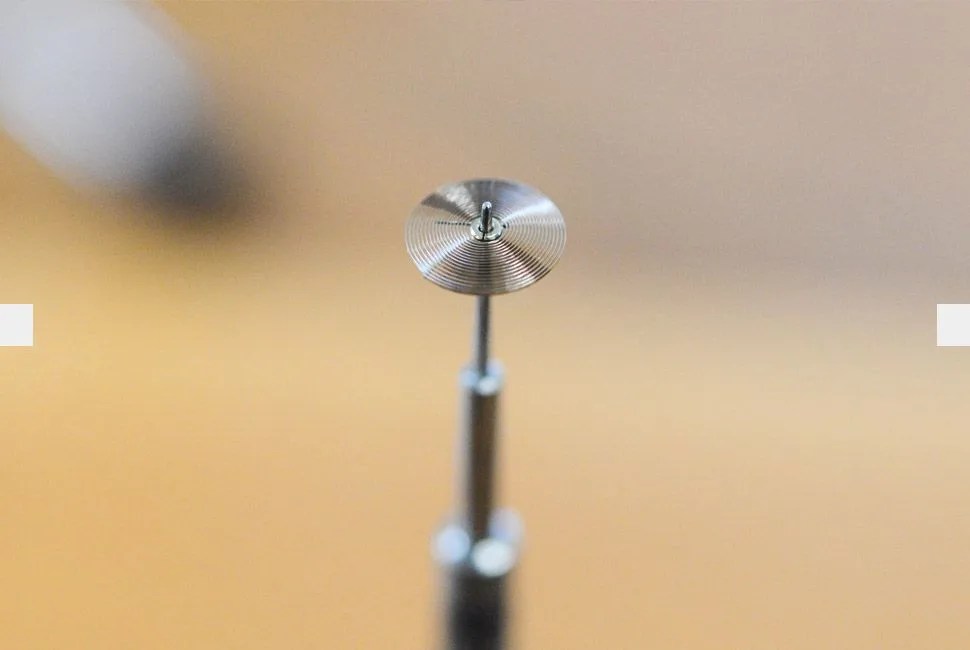

While Montblanc builds most of its timepieces (and indeed some truly exquisite ones) in its Le Locle factory 30 minutes up the valley, Villeret is kept for producing only the most special ones. Indeed, the factory still employs just 35 people and turns out only a few hundred watches per year. The work here is largely manual, from shaping components to decoration to assembly and testing. It is also one of the handful of watch companies that make their own hairsprings in the traditional way, a point of pride for Montblanc. What machines are here date from the 1940s and are meticulously maintained, with parts sometimes being custom-made onsite. This is a place of smells — lubricating oils, chemicals and that familiar scent of an old house, musty but comforting.

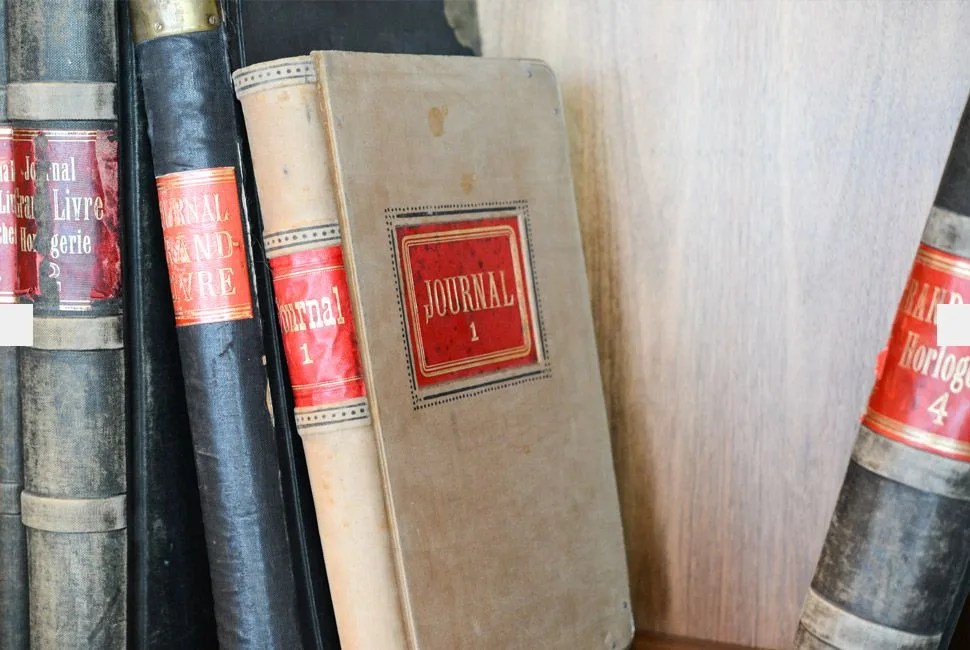

Before our tour we spent time in the library, where the shelves still hold oversized ledgers bearing handwritten notes about components bought and sold in St. Imier, Neuchatel and as far away as Geneva. A tall watchmaker’s cabinet, its wood worn from a century of use, stood in the corner, a drawer casually open to reveal a sheaf of unused Minerva dials, each individually wrapped in paper and looking ready to be fitted into a new chronograph. How tempting to slip a piece of history into a pocket when no one was looking. But in the end, we didn’t, instead opting to take only photos from this magical place that time forgot, and then remembered again.