Welcome to Watches You Should Know, a column highlighting important or little-known watches with interesting backstories and unexpected influence. This week: the Harrison H4 Marine Chronometer “Sea Watch.”

In fourteen hundred and ninety-two, Columbus sailed the ocean blue … but he didn’t have a clue where — or more importantly, how far — he was going. He just aimed ’er west and told the boys to floor it. He was headed to India, he thought, but he ended up in the West Indies; that’s how the Lesser Antilles got their popular name. Columbus had no idea how far west India lay, or how long it would take to get there. He just trusted they wouldn’t fall off the edge of the world — where there be dragons, you know.

The Problem of Navigating on the Open Seas in the 18th Century

The problem of longitude — where you are on the planet, east-west speaking — was the thorniest puzzle of the day, or really, of the 18th century. The standard method of navigating southwest from Great Britain to where the riches of the New World lay was really to go south to the correct latitude, which one could easily determine by observing the North Star, then head west until the guy in the crow’s nest yelled, “Land Ho!” Not really efficient.

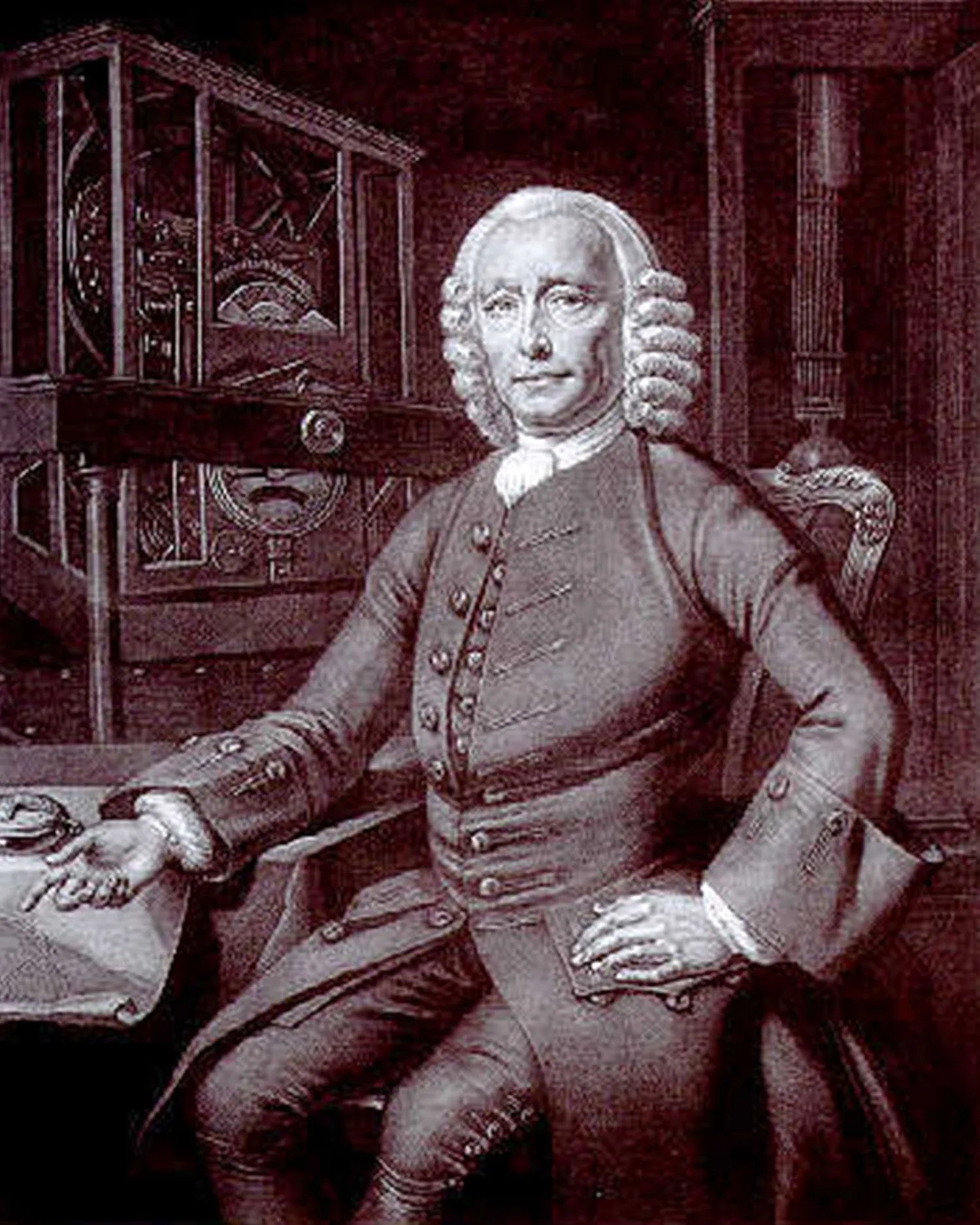

Thus, in 1714, the British government offered the huge prize of £20,000 (very roughly $7.5 million today) to anyone who could solve the longitude problem once and for all. The competition was to be overseen by a newly created Board of Longitude.

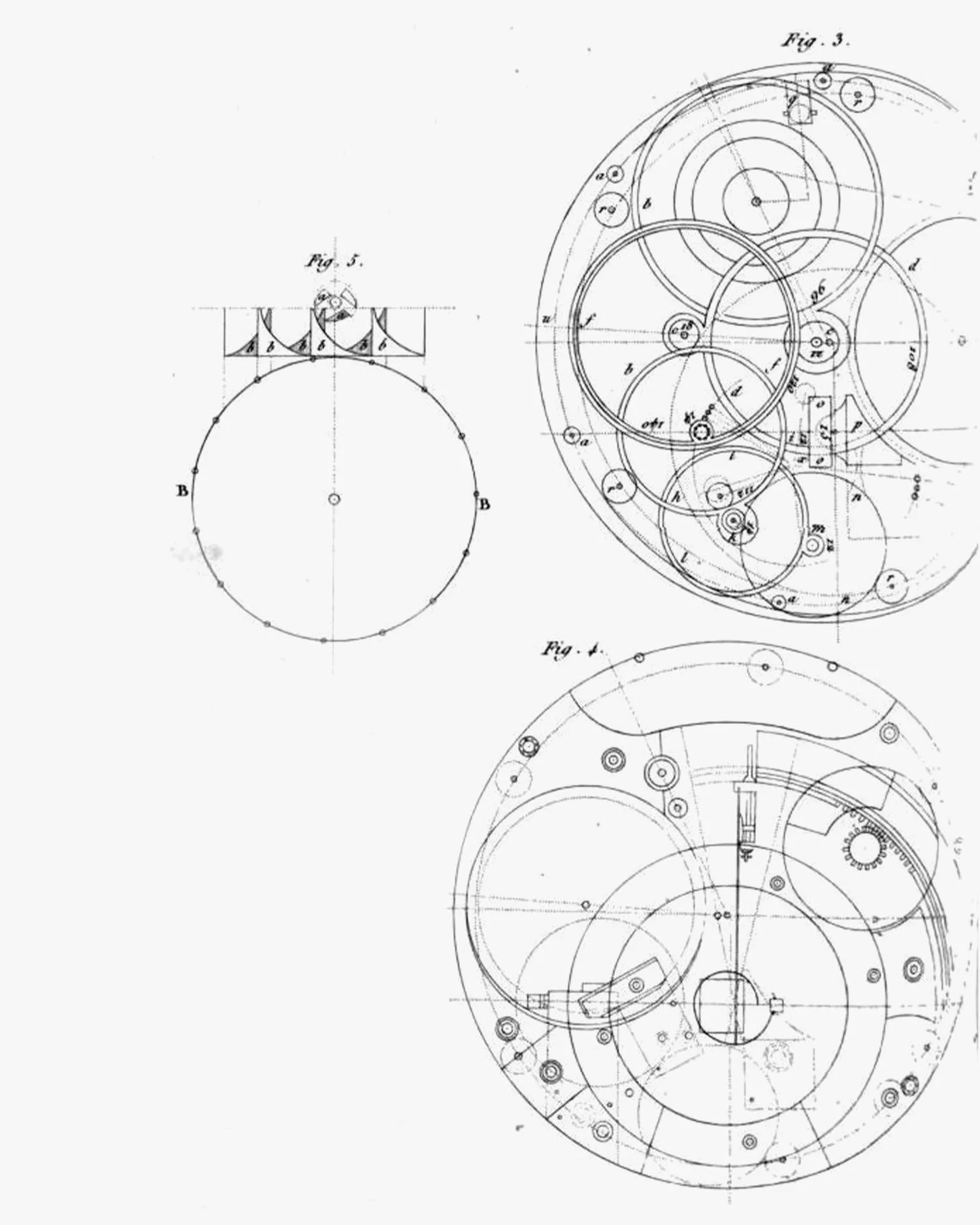

All manner of approaches appeared: lunar tables, complex equations based on the sightings of the planets and many more. The real solution, everybody knew, was to know the precise time where you were on the open ocean and also know the precise time at home. Then it was a simple calculation to figure out how far west — or east — you were. You could do this by sighting the sun at high noon where you were, and if you had a good enough clock for the time back home, you could compare the two and, with some simple mathematics, determine your position.