Imagine a world where virtually all mainstream auto manufacturing companies use Ford engines. Chevrolet, Chrysler, Toyota, Nissan, Audi, Volkswagen, Kia, Honda, Mazda, Hyundai, BMW — all of them source their motors from Ford. Only a few high-end brands with extremely deep pockets and long traditions, like Mercedes, Bentley, Ferrari, and Rolls Royce, make their own power plants. The rest, Ford’s competitors, buy engines from Ford and put their own names on the valve covers.

WEIGHING IN: Why Do Watches Cost So Much? | The Cigar, Simply | The Side Effects of Learning Thricely | Running From Responsibility

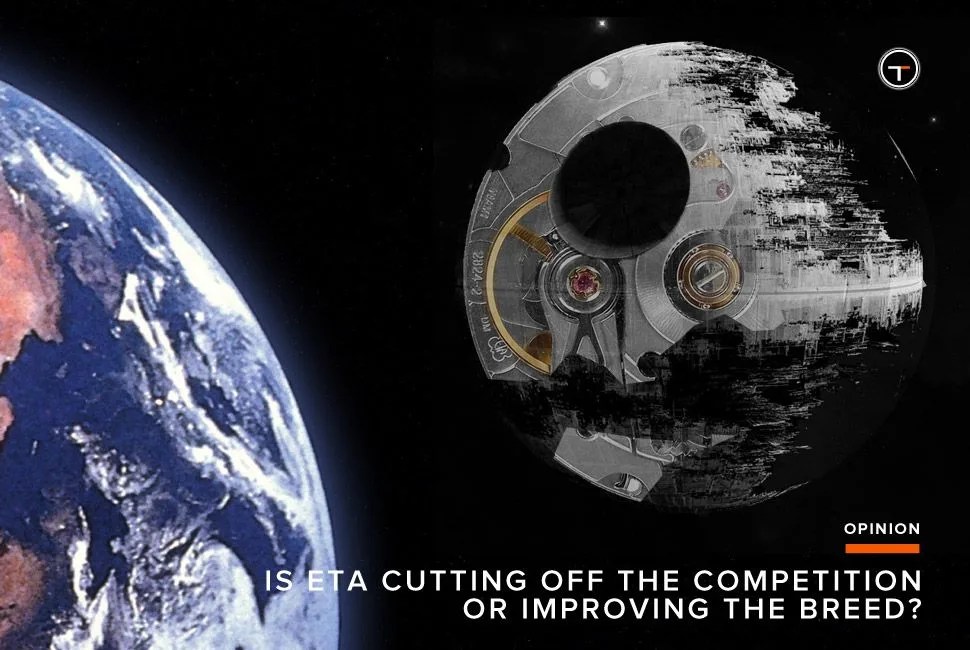

This scenario is roughly true in modern wristwatch manufacturing. Swiss watch movement maker ETA supplies much of the horological world with movements and ébauches (partial movements in need of finishing). Some brands simply plug in the ETA engines and carry on. Others tune them to their own specifications before labeling them as their own. In fact, for reasons we won’t discuss in this article, this situation played a large part in the salvation of the Swiss mechanical watch industry.

Then in 2002 Nicholas Hayek, then chairman of The Swatch Group (ETA’s parent company), announced that ETA would soon begin tapering back the supply of ébauches to the world of Swiss watchmaking beyond their sister brands (Omega, Blancpain, Breguet, Longines, Rado, Tissot, Hamilton, Swatch, and several more). Effectively, the Swatch Group decided to stop selling to the competition, albeit gradually.

Brands would be stronger and healthier for having their own in-house movements — or they would die.

Within the watch community, this caused an uproar nearly akin to the quartz crisis of the 1970s. The majority of Swiss watch brands used ETA movements, and they feared for their economic lives. In 2003 the Swiss Competition Commission launched an investigation — and the pissing match started in earnest. ETA claimed they would wean their customers gradually, giving them time to find other suppliers or develop their own in-house movements. At the same time, they claimed that this was a move aimed at ultimately strengthening the Swiss watch industry. Competition would be improved. Brands would be stronger and healthier for having their own in-house movements — or they would die.

In 2005 the Commission ruled that ETA was in breach of Swiss law as it pertains to cartels. ETA was ordered to continue supplying ébauches to current customers at levels based on then-current supply levels and to gradually reduce numbers over a period of years. This ruling was extended in 2012, with supplies to be reduced gradually until 2019 (2023 for Nivarox products, the temperature-change resistant hairsprings upon which balance wheels are suspended).