Welcome to Watches You Should Know, a biweekly column highlighting important or little-known watches with interesting backstories and unexpected influence. This week: the Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso.

It’s 1930 and you’re a British Army officer in India. What do you do to wile away your spare time? Why, you play polo of course. But the sport of kings is a little tough on any piece of timekeeping equipment that might be strapped to your wrist.

Enter César De Trey, an executive of the soon-to-be-established company “Specialites Horlogeres,” which would subsequently evolve into Jaeger-LeCoultre a few years later. In 1930, De Trey was in India on business, attending a polo match in his spare time. He was approached by a player who held up his broken watch and asked (or challenged — history is unclear) De Trey to make a watch that could withstand the rigors of the polo grounds. (Why players didn’t simply leave their wristwatches in the locker room, history did not record.)

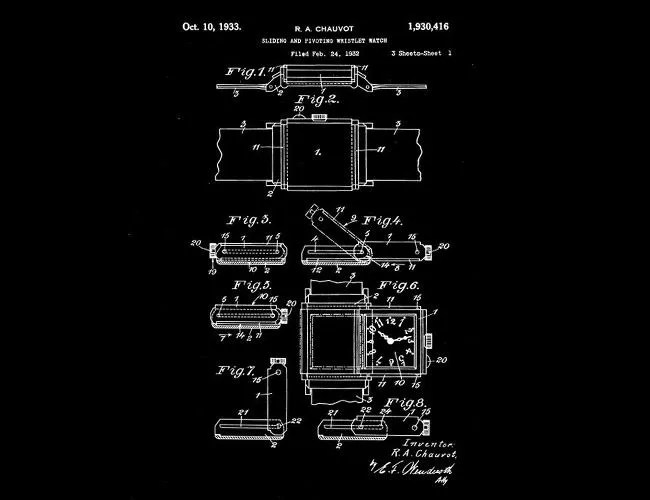

Back home in Switzerland, De Trey thought about the problem and discussed it with his friend Jacques-David LeCoultre and the French firm Jaeger S.A. The work was entrusted to Jaeger, who then enlisted the services of French designer René-Alfred Chauvot. Chauvot developed and patented a case mechanism that allowed the watch to be flipped over while on the wrist. Thus, the Reverso was born, and wristwatches all over the polo fields of India were protected from the strikes of errant polo mallets and balls.

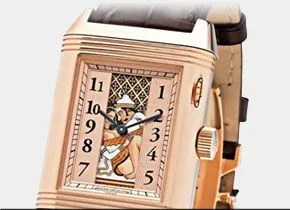

What this enterprising team of watch designers and makers had also unknowingly done was create an Art Deco icon the form of which would not be altered significantly from 1931 to today. To be sure, over the years the Reverso has seen countless versions, alleged patent squabbles, clones and wannabes from both sides of the Atlantic, a brief suspension of production, and perhaps even a flirtation with quartz. The use of quartz movements was ultimately decided against, even though the majority of the JLC line was quartz powered in those days (early 1980s).

Production remained low during World War II and in the subsequent decades, and the watch briefly fell out of production in the 1970s. Legend has it that the Italian JLC distributor Giorgio Corvo, who was also a connoisseur and collector, discovered a small cache of cases during a visit to the JLC manufacture in Switzerland in 1972. He persuaded the company to sell him all 200 cases, had them fitted with mechanical movements and took them back to Italy, where all 200 watches sold within a few weeks. The legend, which JLC has never confirmed, adds that Corvo was instrumental in convincing the manufacture to resist the quartz temptation and use only mechanical movements in the Reverso.

Reverso à éclipses