Driving across the farm country of central Pennsylvania from Columbia to Mount Joy, I noticed that the highway signs listed mileage to exits in tenths of a mile instead of the usual quarter mile estimates I’d always seen. Was this a hint as to why this part of the United States was once such a cradle of American watchmaking — an obsession with precision, perhaps?

To the casual observer, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, with its tidy towns and the waft of manure from plowed fields on the spring breeze, is a far cry from the vaunted watchmaking regions of Europe. But there are similarities between this rolling farmland and the mountain valleys of Switzerland and Germany: a history of rural isolation, strong Puritan work ethic and cold winters.

A mechanical timepiece is truly a universe on your wrist, whether conceived in the workshops of mountain villages in the Jura or the farm country of central Pennsylvania.

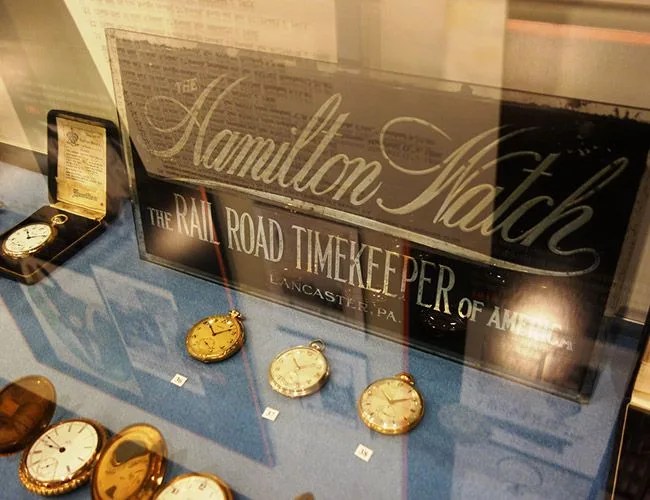

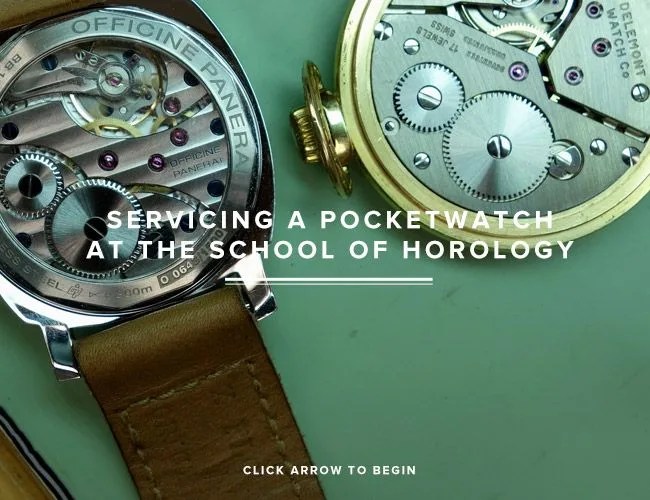

I flew in to Harrisburg International Airport one balmy weekend in April with two family heirlooms in my carry-on bag, both Hamilton pocketwatches I intended to bring back to their birthplace: Lancaster. They had belonged to my grandfathers, one on each side of the family tree. Both are railroad-issue timepieces, sturdy and accurate in their day, with lever-set movements, gold plated cases made somewhere in Illinois, and enamel dials. One, a calibre 924, was built prior to 1910 and was in rough shape, missing its hands and both its hairspring and mainspring, no doubt cannibalized sometime during the mid-century to repair another watch. This one belonged to my father’s father and spent countless years in the chest pocket of his coveralls while he worked as a line foreman for the Soo Line railroad. The last watchmaker’s signature scratched inside the caseback says “1948.”

The other Hamilton, a 1920s calibre 992, belonged to my mother’s grandfather and had seen considerably more pampering. The decorated case still shines, and a few twists of the crown starts the big balance wheel swinging its dutiful 18,000 beats per hour. If not for a small chip on its Montgomery dial, this one could have been made within the past decade rather than the Roaring ’20s.

Great Historical Hamiltons