Let’s get one thing out of the way: a chronometer is different than a chronograph, though one can also be the other. We’ve heard the terms confused one too many times, and while we’ll forgive past sins, it’s time to know the difference once and for all. Read on.

The term chronometer comes from two Greek words, and roughly means “time measurer.” The word first came into use in the early 18th century with specific reference to timepieces designed for navigational use onboard ships. In those days — before LORAN, radar and GPS — getting a ship around the world, much less around a rocky peninsula, was a challenge to mariners. Two parameters are necessary to determine your exact whereabouts on the globe: latitude and longitude. Latitude, your position relative to the Poles, can be determined by the angle of the sun relative to where your boat is bobbing; that was discovered and used by sailors relatively early on.

To be marked as a chronometer shows a company’s commitment to accuracy.

The other parameter, longitude, is a bit trickier. So tricky, in fact, that a lack of accurate measurement caused ships to regularly miss their targets by hundreds, even thousands of miles — if they didn’t founder on rocks or break up on hidden reefs first. The British government took this problem very seriously, recognizing that a nation that could travel the seas with confidence would have a much easier time ruling the world. So they put up a large sum of reward money in a contest known as the Longitude Prize in 1714 to develop a means of reliably determining a ship’s precise location east to west.

While some contestants opted to use the stars as a guide, the use of an accurate timepiece, a chronometer, was more widely accepted as the real solution. By knowing the exact time at home port and by taking a “sun shot” at high noon using a sextant, a mariner could determine how many longitude lines of the globe he had crossed and thus determine his position. In 1761, 47 years after the British government offered their reward, the famed watchmaker John Harrison finally produced a reliable chronometer that would be accurate even through the temperature changes and rolling swells onboard a sailing vessel. He was awarded the prize (£14,315), the British Empire swelled, and the first true chronometer was born.

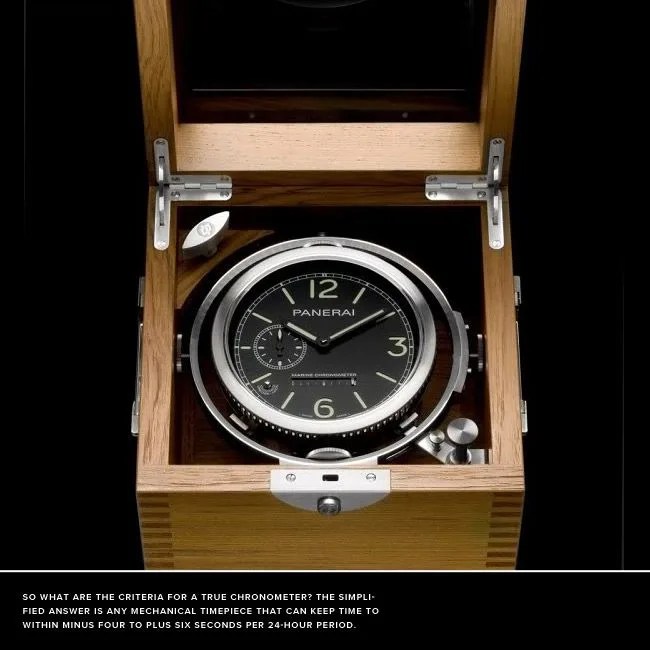

Though the term chronometer was first used for marine navigational clocks, it was soon applied to any timepiece that met specific criteria for accuracy. The old adage, “a broken clock is right twice a day” helps illustrate the difference between precision and accuracy. Precision is the ability of a timepiece to be correct at any one moment. Accuracy is that timepiece’s ability to be precise day in and day out. This is no easy feat, given the malicious forces of gravity, temperature, magnetism and friction, which prey on the delicate mechanism inside a watch. It is also what makes earning the label “chronometer” so prestigious, even 250 years after Mr. Harrison’s timepiece debuted.