The complicated 18th-century pendulum clock was in a blackened state of disrepair and deemed unfixable by Sotheby’s auction house. Known as the Pendule Sympathique, it was a showcase of the legendary watchmaking genius of Abraham-Louis Breguet, produced by his own hand in the late 1700s and incorporating astounding mechanical features and craftsmanship. But time had treated it roughly.

It was a monumental challenge, but in 1990, several years before establishing his eponymous watch brand, watchmaker Michel Parmigiani managed to successfully and beautifully restore the clock. This was a significant achievement, and just one example of the horological wonders to which he’s given a second life.

Despite the watch industry’s constant talk of history and tradition, the field of restoration is often overlooked. It’s a discipline that takes watchmaking and associated skills to another level, often requiring watchmakers to act as detectives in order to reverse-engineer missing or damaged elements. Sometimes, they even have to make the tools needed to recreate components from scratch, mine centuries-old hand-written archives for clues, and rediscover lost crafts and techniques, all while staying as true to the original item as possible. Restoration is where many of the most respected names at the highest level of modern watchmaking got their start.

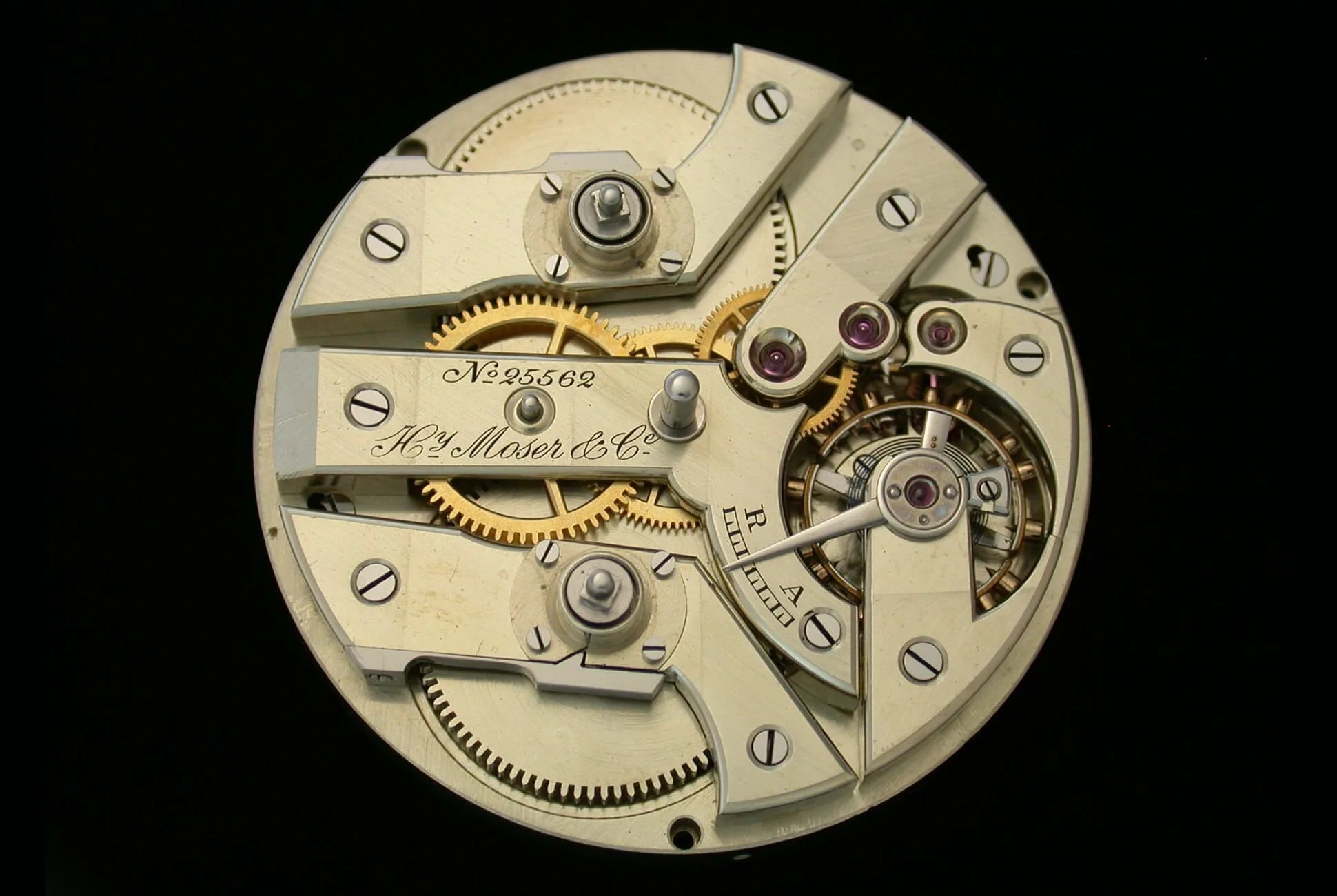

The Parmigiani watchmakers in Fleurier, Switzerland, recently showed Gear Patrol an example of an incredibly thin, restored pocket watch from around 1840 along with pictures of its pre-restoration state. It had been missing a critical component: the balance wheel. Like forensic horologists, they were able to determine the size of the original balance wheel based on the patterns of oxidation left on the metal beneath where it had been. It now not only functions, but gleams, in all the intricate, engraved glory its long deceased creator intended.

When rare historical objects like bejeweled automatons, Fabergé eggs, or ultra-thin pocket watches need to be restored, the workshops of Parmigiani is where many of them go. It’s even where the Patek Philippe Museum often turns for its restoration needs. This part of Parmigiani’s business quietly continues alongside the modern brand making wristwatches directly influenced by restoration projects and the unique horological features uncovered in the process. Below are some notable examples of mechanical marvels that help illustrate the world of restoration, Parmigiani’s specialized expertise, and the surprising creativity of the era these exotic items exemplify.

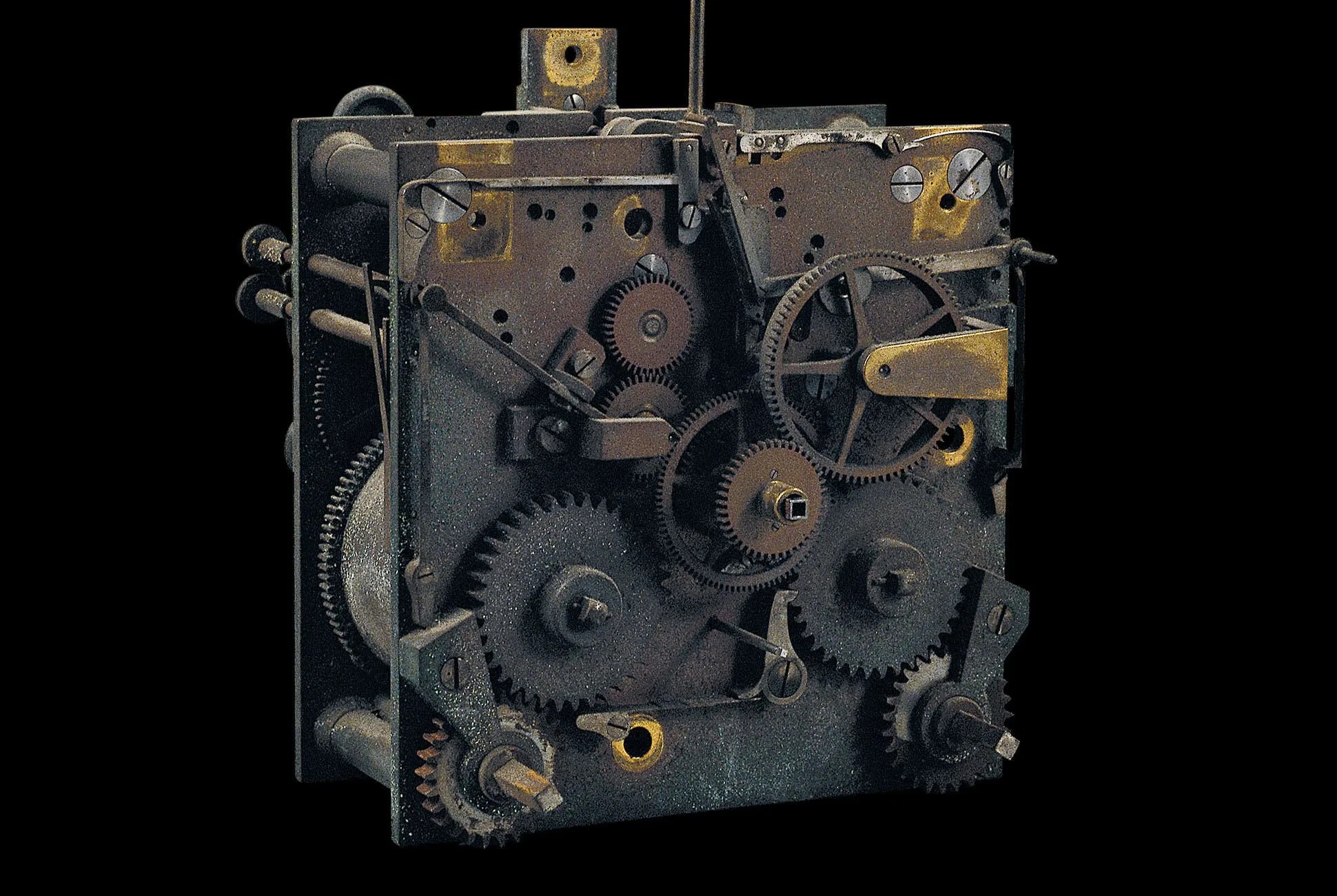

Breguet Pendule Sympathique

3 photos

The Breguet Pendule Sympathique mentioned above was a landmark piece for Michel Parmigiani, but it’s also an unusual and impressive creation in its own right, unlike anything else in existence today. More than a pendulum clock, it incorporates an upper dock that holds a companion pocket watch. In this ingenious system, the pocket watch needs merely to be docked and the mechanism will automatically wind it and synch its time to the clock’s. And all this came centuries before your phone’s charging dock or watch winders for automatic watches.

In comparison to this unique feature, the clock’s chiming mechanism and extensive decoration almost seem standard, but are in reality startlingly complex. The clock’s exterior is decked in red tortoiseshell with pewter and gilt brass inlay. Breguet is believed to have made only around a dozen such clocks, and this particular one was made for the Duc D’Orléans for a price of 10,000 18th-century francs. In 2012, it sold at auction for $6.8 million.