JH

JHSomeone once said that writing about music is like dancing about architecture. But while I’m sure music critics have their own challenges, I suspect they have an easier time explaining what they do than we watch writers, who fetishize the arcane minutiae of an anachronistic art. But I’ve learned to respond to questions about my chosen subject matter by simply unscrewing the case back of a mechanical watch to reveal the magic within. How can one not marvel at this miracle of micro-engineering that keeps time with an accuracy that is the equivalent of a bullet hitting a one-inch by one-inch target a mile away? All by means of tiny springs and gears. Combine this with the fact that a watch is one piece of gear that can be a constant companion through all life’s adventures, from weddings to triathlons to job interviews. I’m often asked how I got started loving watches and so here is a short history of my own evolution as a watch nerd.

I’m from a railroad family. A long gone, thrice-removed cousin was one of the founders of the Northern Pacific Railroad, my grandfather was a foreman on the Soo Line and my father drove spikes for a summer job. Despite the fact that the closest I ever got was playing with an electric train set, I somehow was deemed worthy enough to inherit railroad-issue Hamilton pocketwatches from both grandfathers. And while both pieces showed the patina from regular use and are not terribly collectible, they were enough to plant a seed in me that blossomed into a full-blown love for all things horological.

In 1986, when I was 16, an admittedly nerdy teen-aged Walter Mitty, I wandered past a jewelry store display in a shopping mall. There, perched on a stand was a burly steel dive watch, a Seiko with a blue and red turning bezel, bold dial and thick rubber strap. I was smitten. Strapping this watch on my wrist would surely imbue me with instant adventure cred and a sex appeal that was sorely lacking with my puny Armitron. I found the courage to inquire about said timepiece and the salesperson told me this one didn’t need a battery. He wound it up and I saw the seconds hand smoothly sweep around the dial. I had to have it, no matter what the cost. Well, it turned out to be $80, a steep amount for an unemployed teenager but after a summer of painting houses and cutting lawns, I had enough to buy that Seiko. Never mind that it kept terrible time, I felt like Neptune himself with that watch on, and I rarely took it off. Alas, the sex appeal never materialized but now my love of watches was deeper still.

There, perched on a stand was a burly steel dive watch, a Seiko with a blue and red turning bezel, bold dial and thick rubber strap. I was smitten. Strapping this watch on my wrist would surely imbue me with instant adventure cred and a sex appeal that was sorely lacking with my puny Armitron.

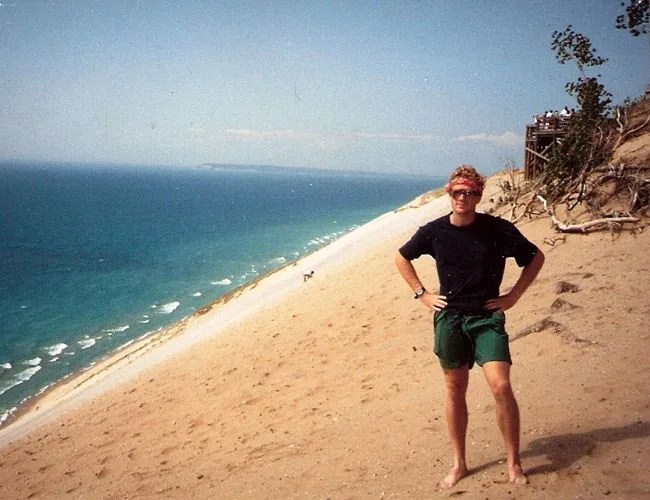

By the late ‘90s, the Seiko was long gone, sold in a weak moment, the first of what would be many regrettable timepiece heartbreaks. I was working part-time in outdoor shops and the rugged lifestyle being sold there, combined with weekends spent running, biking, paddling and camping led me to a logical love for the new genre of so-called “wrist-top computers,” specifically those sold by the Finnish brand, Suunto. I got a pro deal on a bright orange X6, which tracked altitude, weather systems and had a compass and countless alarms. But the best thing about this watch was that it could be connected to a computer with a serial cable (remember those?) and you could download all your data. Needless to say, the Suunto ravenously consumed batteries but at least they were user-replaceable and I wore that watch everywhere for years. I even got married in it, at the foot of a glacier in Alaska and it accompanied me on climbs of 14,000-foot Colorado peaks and on a bike trip across the mountains of Sri Lanka.