There’s a reason you don’t hear the term “Asian watchmaking” often: watchmaking in the East, though powerful, is most easily grouped into Japanese, Chinese, and other country-focused categories. Studying these markets together is like lumping together British, Swiss, and German watchmaking — they have different histories, different priorities, and different meanings to the modern watch collector.

Yet there’s value in exploring the wide scene of watchmaking in Asia, if only because it’s understudied and under-appreciated. So let’s ask the question: what could we mean when we talk about these separate groups and their meaning to global watchmaking and watch ownership?

China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan are important production hubs — not just for low-end, mass-produced pieces, but for many parts that go into watches made by worldwide microbrands and, yes, your “Swiss-made” beauty, since that label means that only 60% of each timepiece must have been produced in Switzerland. Hong Kong, for instance, was second only to Switzerland for watch exports by value in 2017. China, its industry at different times hobbled and intensified by intense government control, leads exports based on number of units, and exported 688 million completed watches worldwide between 2013 and 2017.

Asian countries are not just producing watches — they’re buying them at historic rates. Both China and Hong Kong are monsters of the luxury watch market share. Together, according to the Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry, Asian countries accounted for 40% of the total Swiss luxury watches purchased worldwide in 2017 — more than $8 billion. With that sort of purchasing power, you better believe that the whims and taste of Asian buyers drive the market for the rest of us.

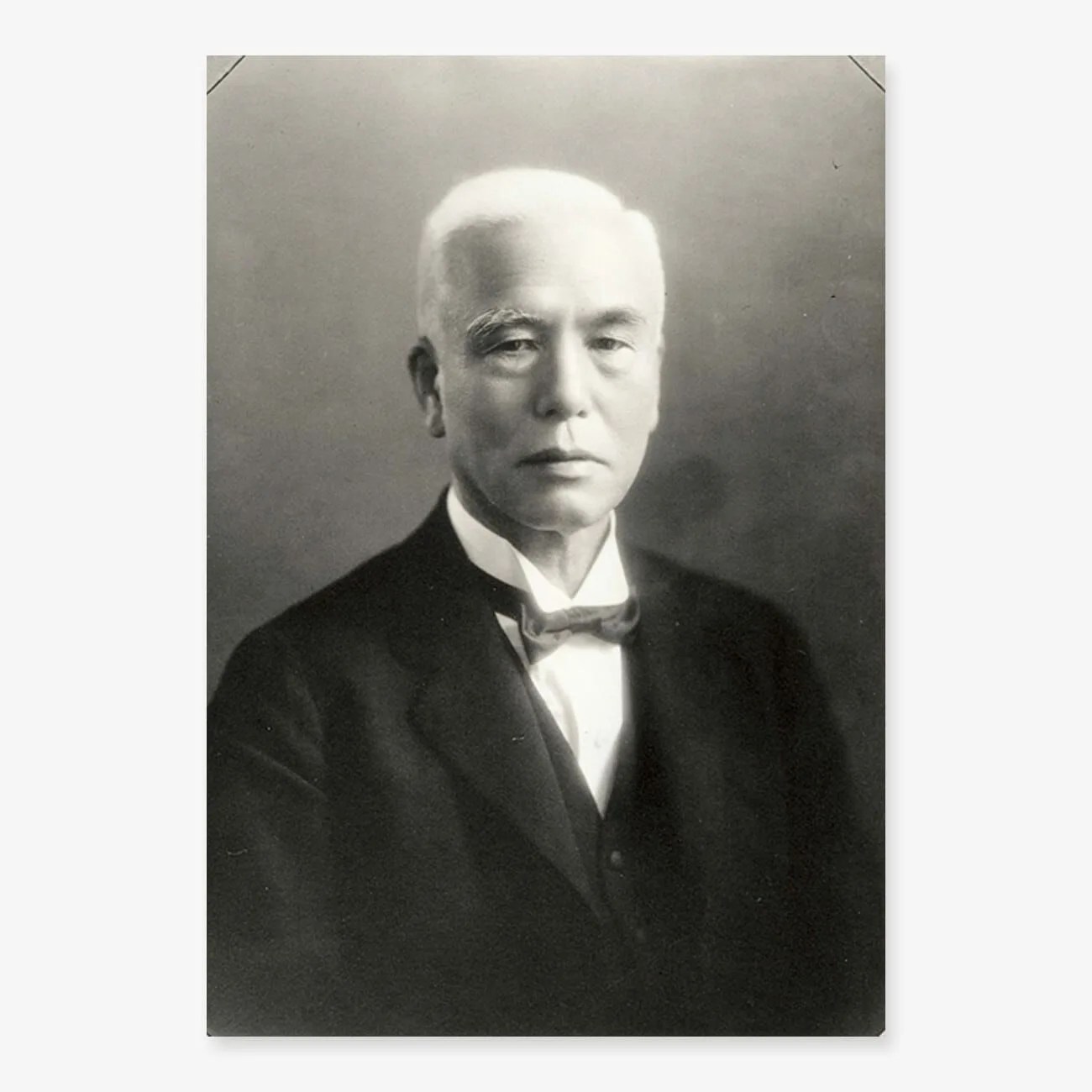

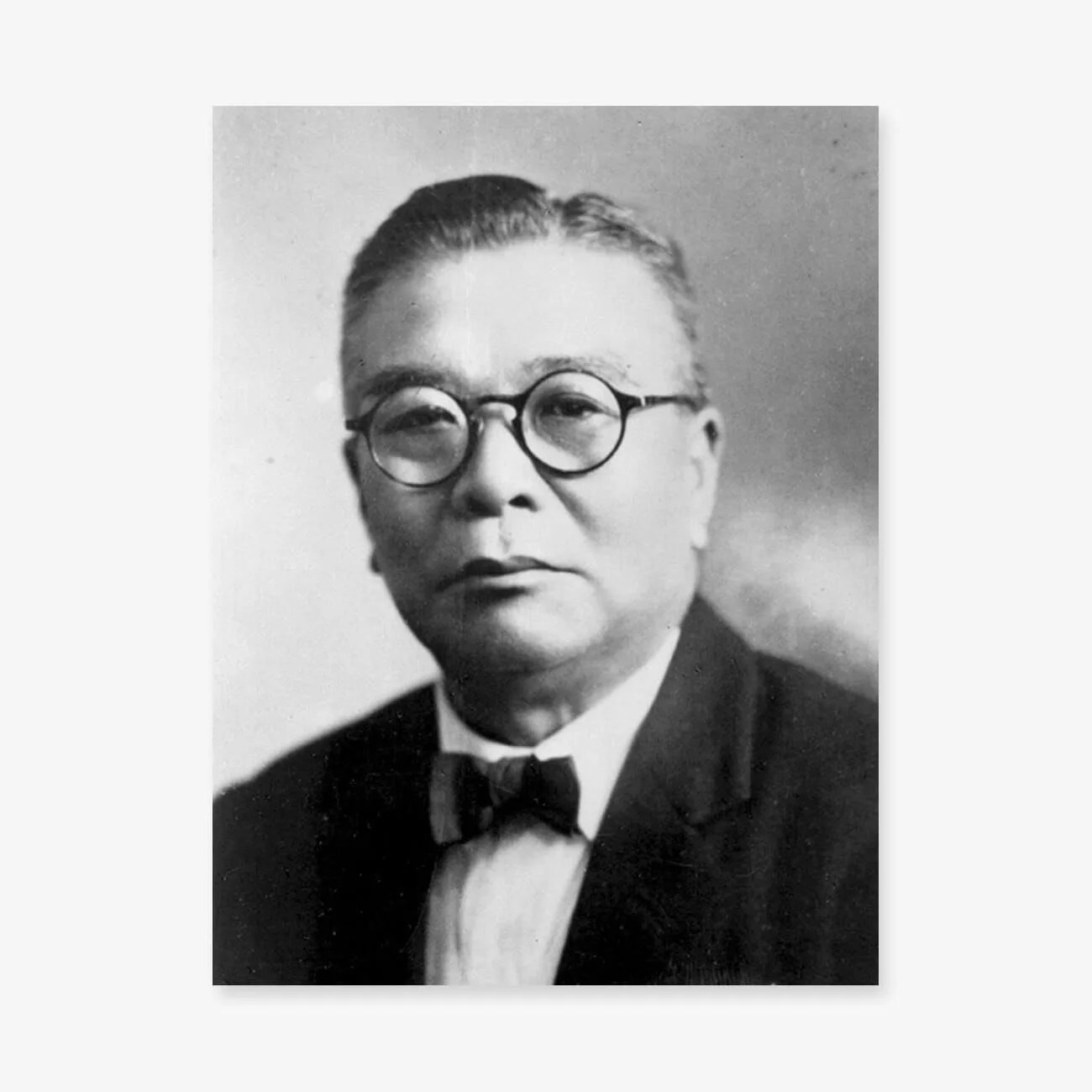

And then, of course, there’s the story of the East’s most iconic brands themselves. These center around Japan, whose history and modern prominence form the most important narrative for Western watch collectors. In the 1890s, Japanese watchmakers began building pocket watches with lever escapements; by the end of the Meiji era, in 1912, according to the Japan Clock & Watch Association, 20 factories turned out 3.8 million timepieces a year. Practically all Japanese watchmaking industry was destroyed during WWII, but in the 1950s and ‘60s, Japan determined it would become the “Switzerland of the East.”

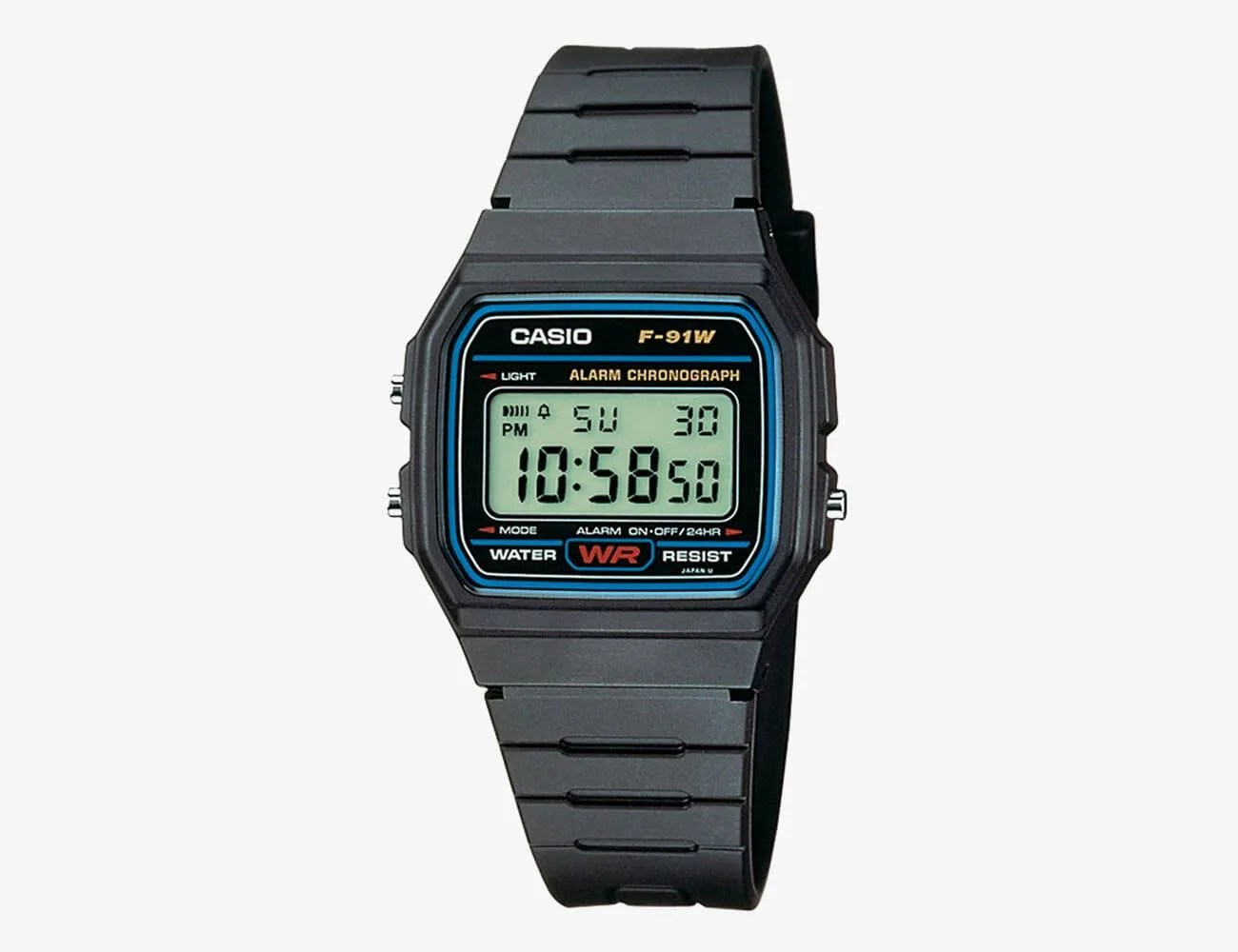

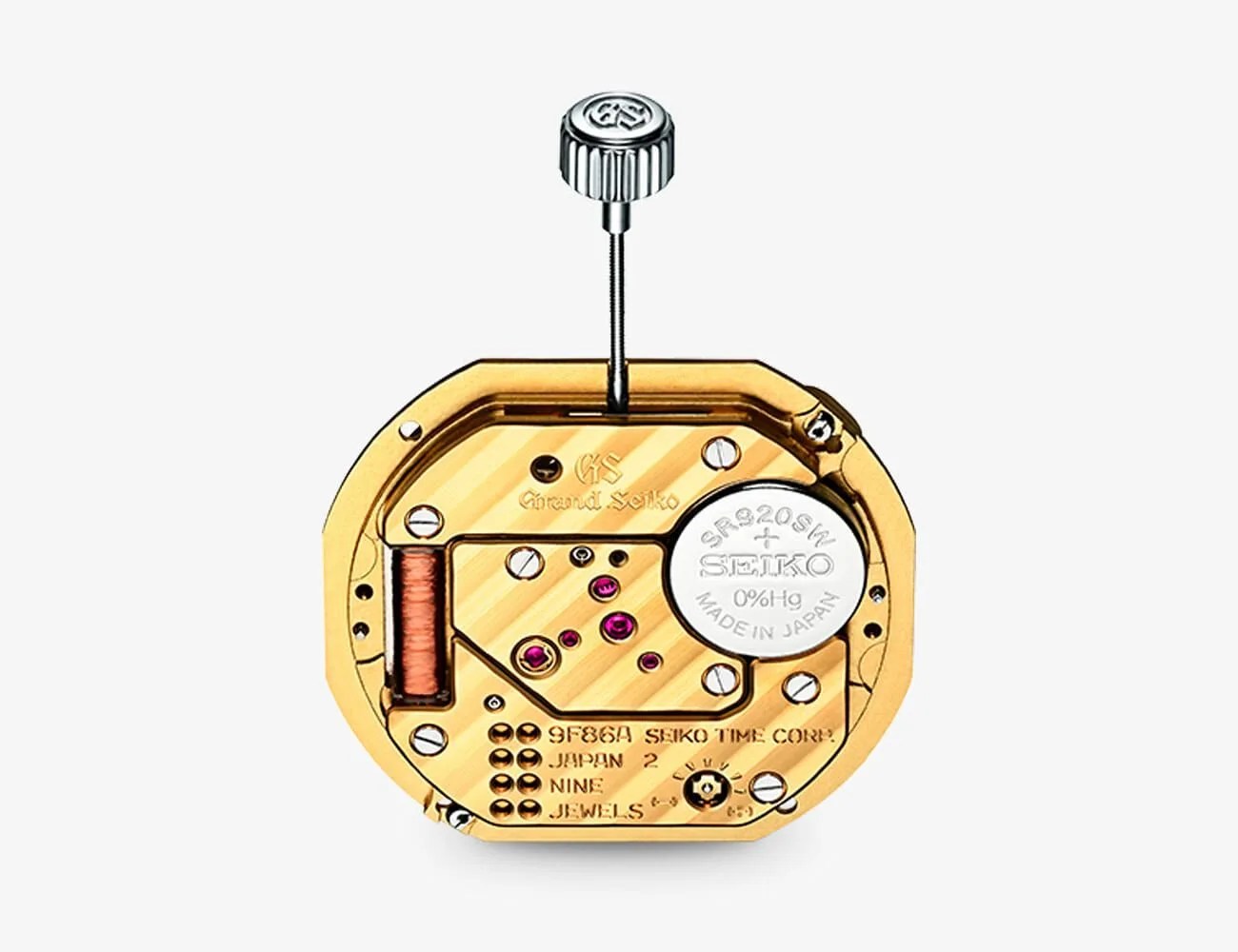

Production during the Korean War boomed in the 1950s, and by the 1960s and ‘70s, technological innovation and quality had made Japanese watchmaking famous worldwide. There might have been a “Quartz Crisis” in Europe, but not so in Japan, where the new technology drove innovation of all kinds (a small wonder, since the Japanese invented the quartz watch). Today, Japanese makers are some of the largest manufacturers of mechanical movements and of completed watches, and shipped some 65 million timepieces in 2017.

Though there are much deeper histories of these watchmaking feats, burgeoning markets, and industrial powerhouses, the best way to study such a wide swath of watchmaking is to look at the watches themselves. This is truly what differentiates Chinese, Japanese, and other Asian watchmaking from the Germans, the British, the Swiss, and the Americans. Asian brands have strived, and in many cases succeeded, to match quality from these markets; they’ve become some of the largest manufacturers of watches, and mechanical movements, in the entire world; they’ve shaken the watch world to its very core with a technological revolution, and steered the way we think about our favorite kinds of watches, from divers to dress watches.