It’s well established in watch lore that in the early ’80s, after accidentally destroying his mechanical watch, Casio’s head of watch design Kiku Ibe challenged himself and his team to build an indestructible watch that could, notably, withstand a 10-meter fall. Ibe’s team built some 200 prototypes and, literally, threw them out the window. What seems like a high-school physics project eventually birthed the original G-Shock, a plastic-cased digital watch that spawned one of the most iconic watch lines in timekeeping history.

Before the dawn of G-Shock, watches were a very small part of Casio’s electronic empire, but today, G-Shock is “the largest asset of Casio,” according to Senior Executive Managing Officer Yuichi Masuda. According to Casio, sales of G-Shock watches are at their highest, thanks to a shift in strategy. The brand no longer sells just humble, tough digital watches — rather, Casio has shifted to offering the classic G-Shock formula with higher-end materials and upgraded functions.

There’s a good reason for this: by Casio’s estimate, the wristwatch market comprises about 1 billion timepieces annually, and increasingly sports and smart wearables are cutting into that, by about 130 million units (again, according to Casio’s own research). Casio naturally wants a piece of this action, but acknowledges exactly where its strengths are; though the brand has created some full-on smartwatches (i.e., those that can run third-party apps), it intends to stick to sports and fitness-oriented wearables, rather than compete with the likes of Samsung and Apple.

What this means is that G-Shock is focusing on so-called “hybrid smartwatches,” traditional quartz watches imbued with smart technologies like Bluetooth connectivity, atomic timekeeping and activity tracking. Potentially, more features will come in the future like the re-addition of an improved heart rate monitoring system (Casio once featured heart rate monitoring on some watches back in the 1990s) and ways to extend battery life (Masuda mentioned a system that could use body heat to re-juice a watch battery).

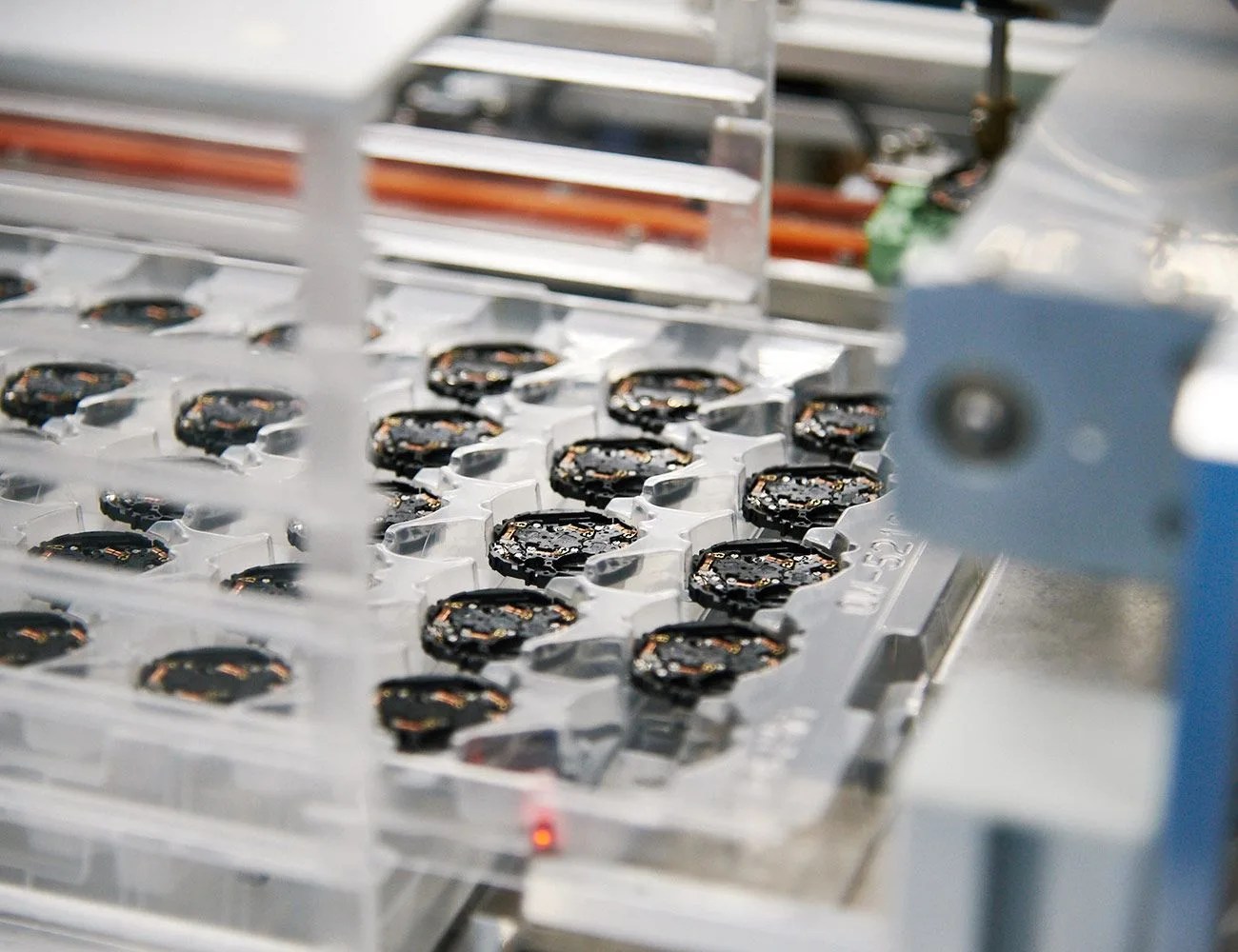

Factor in G-Shock’s increasing use of finished metals for its high-end products, and you have a version of G-Shock that looks much different than that of the ’80s and ’90s (hell, they didn’t even have a high-end line back then), even if the overall aesthetic and mission has remained the same. Similarly, G-Shock’s testing and production facilities have come a long way since the early days of tossing watches out an open window. In Japan, the G-Shock line has both a dedicated R&D facility in Hamura — a suburb about an hour west of Tokyo — and a movement production line in Yamagata Prefecture.