In 2013, a surprising figure was dropped on the watch industry: Japanese watch sales had topped $2 billion, a number untouched since the late 1990s. This boom is due in part to changing perceptions of what Japanese watches bring to the table. The best case study in this shift is the world’s largest watchmaker of the past 30 years, Citizen.

When I speak with many younger or first-time watch buyers, I find that some are seeking out vintage watches (a daunting proposition unless you’re purchasing from well-vetted shops like HODINKEE and Analog/Shift); some are into unique upstarts like Nomos, Uniform Wares and Autodromo; some are on the hunt for ultimate classics like the Speedmaster. But many also seek out the sheer value-to-function ratio of a Citizen Promaster or a Seiko 5. Spend enough time with a Swiss watchmaker and they’ll agree that these watches are excellently made for their price.

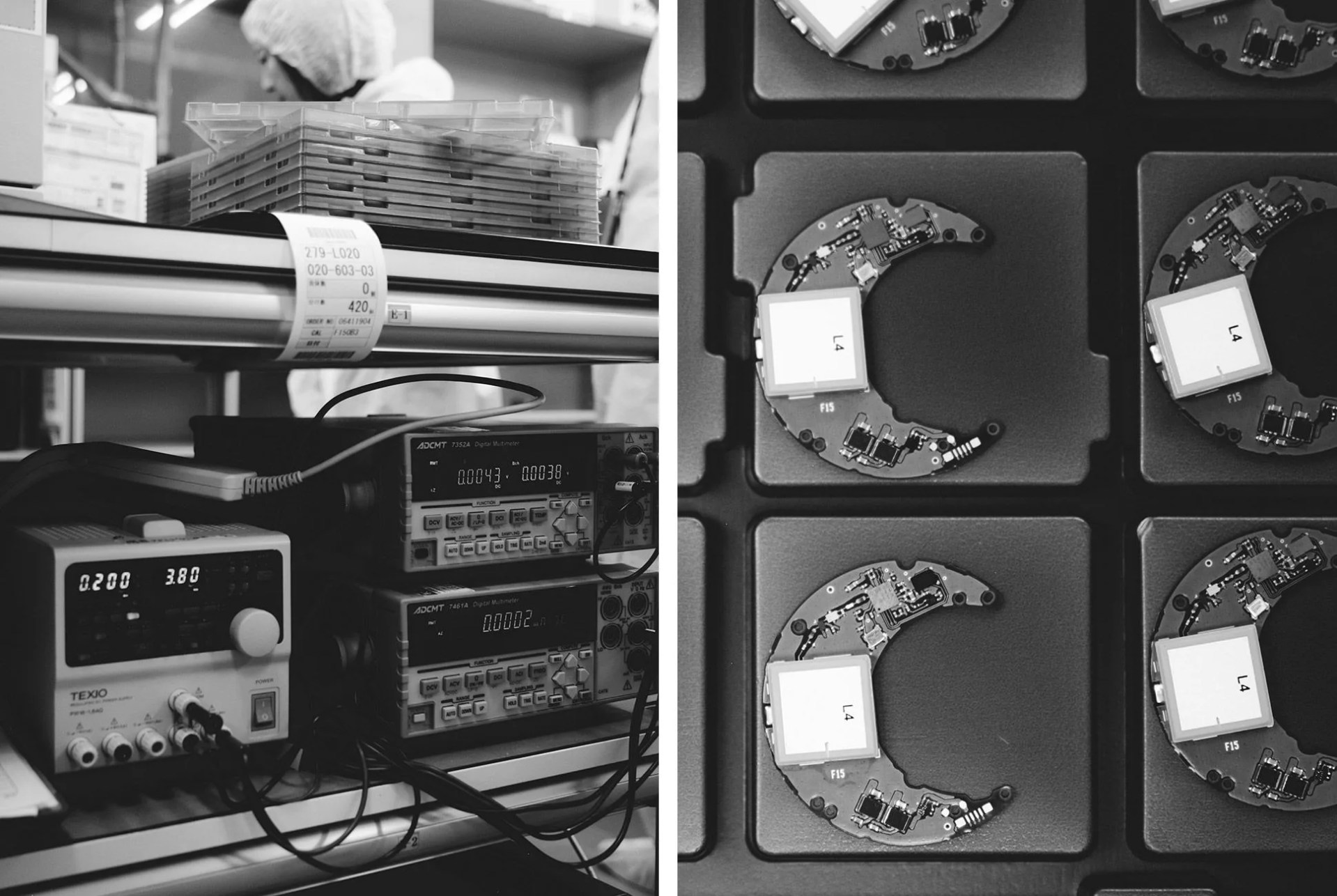

But Japanese watchmaking isn’t just quartz movements and value anymore. Take, for example, the Citizen Eco-Drive One, released at this year’s Baselworld. An impossibly thin analog watch, its case is only 2.98mm thick; the movement inside measures just 1.00mm. To accomplish this, Citizen had to make a bezel out of cermet, a composite of ceramic and metal. Despite the thinness, Citizen was able to advance its own Eco-Drive technology. The One can run up to 10 months on a single charge and is water resistant to 30 meters.

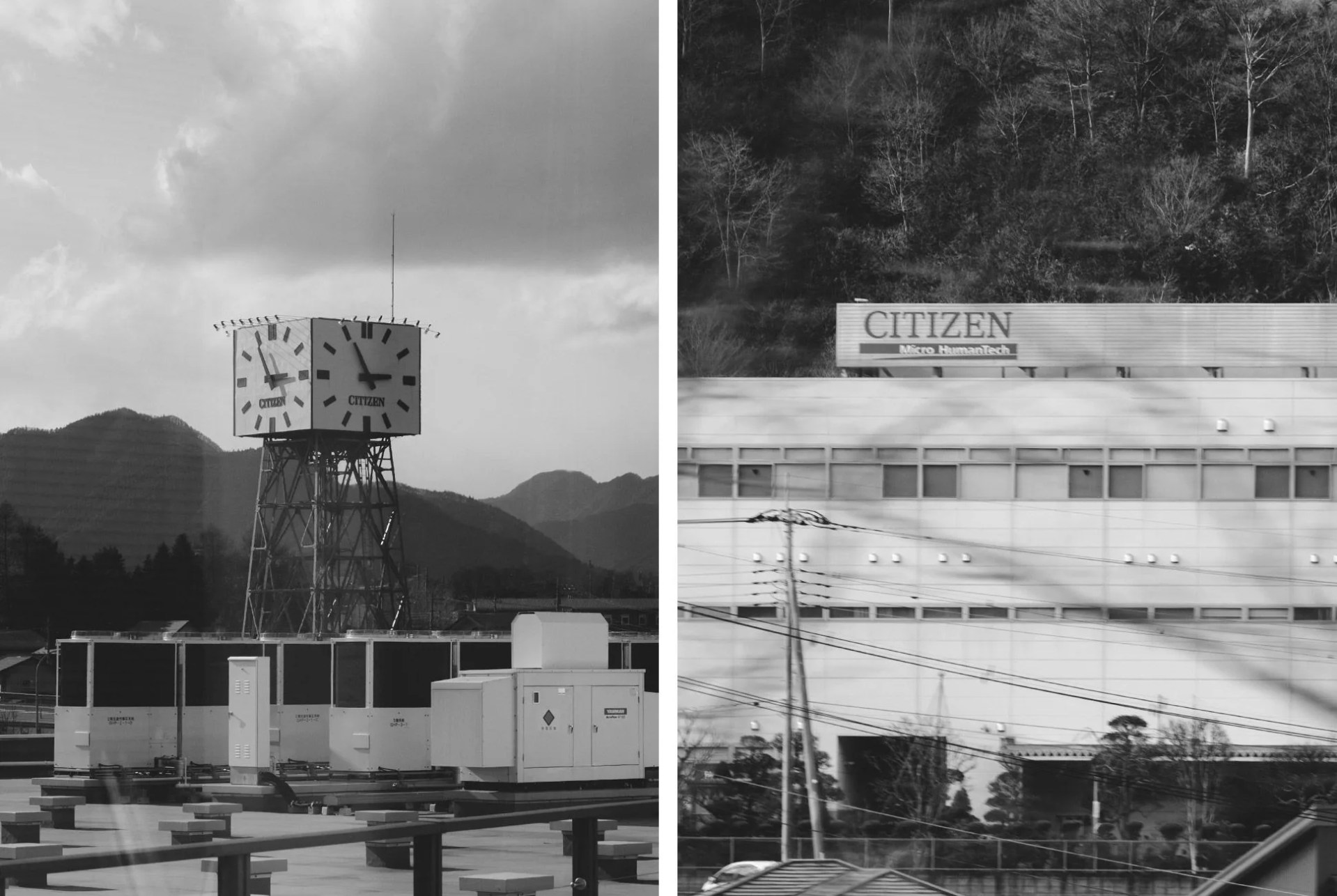

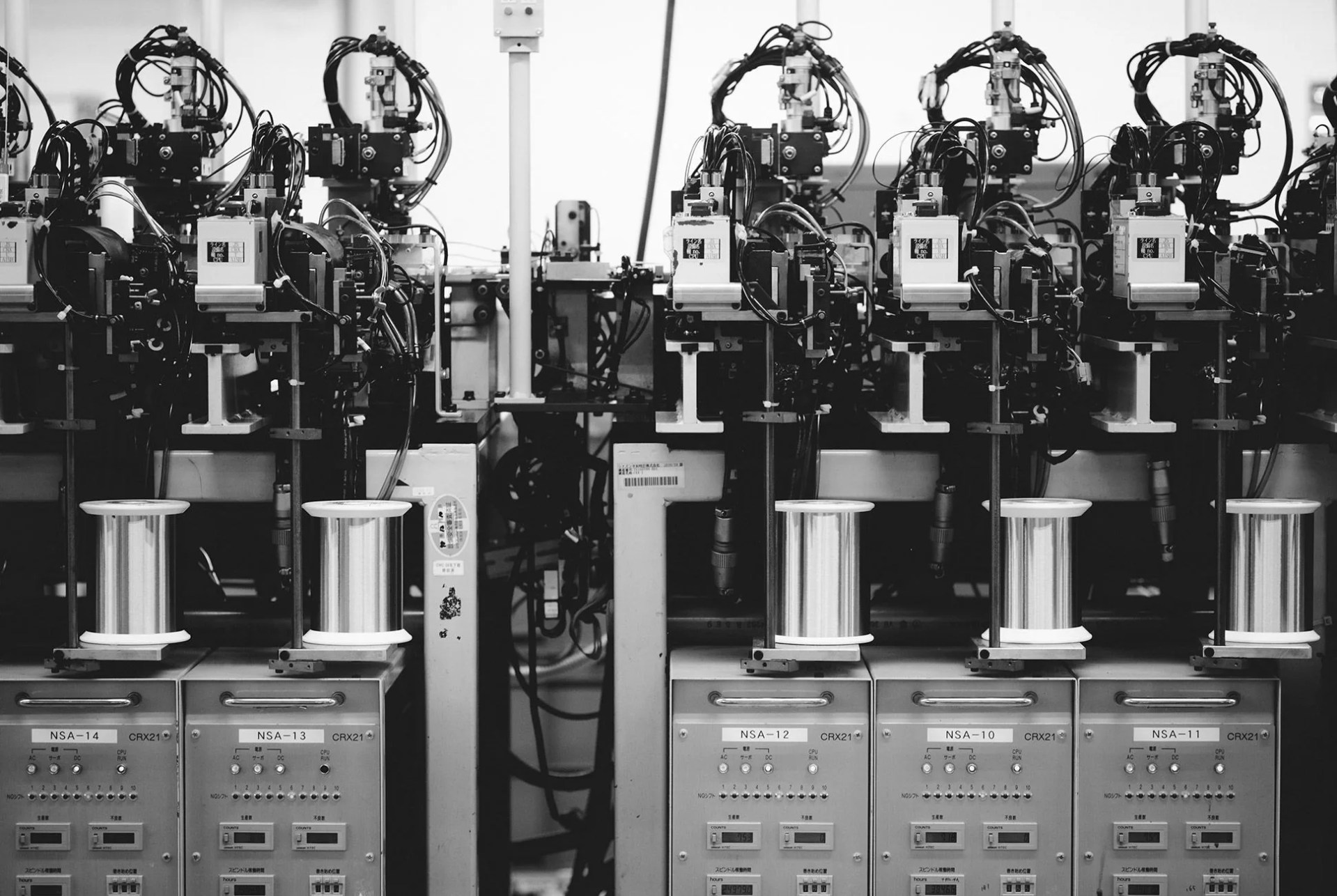

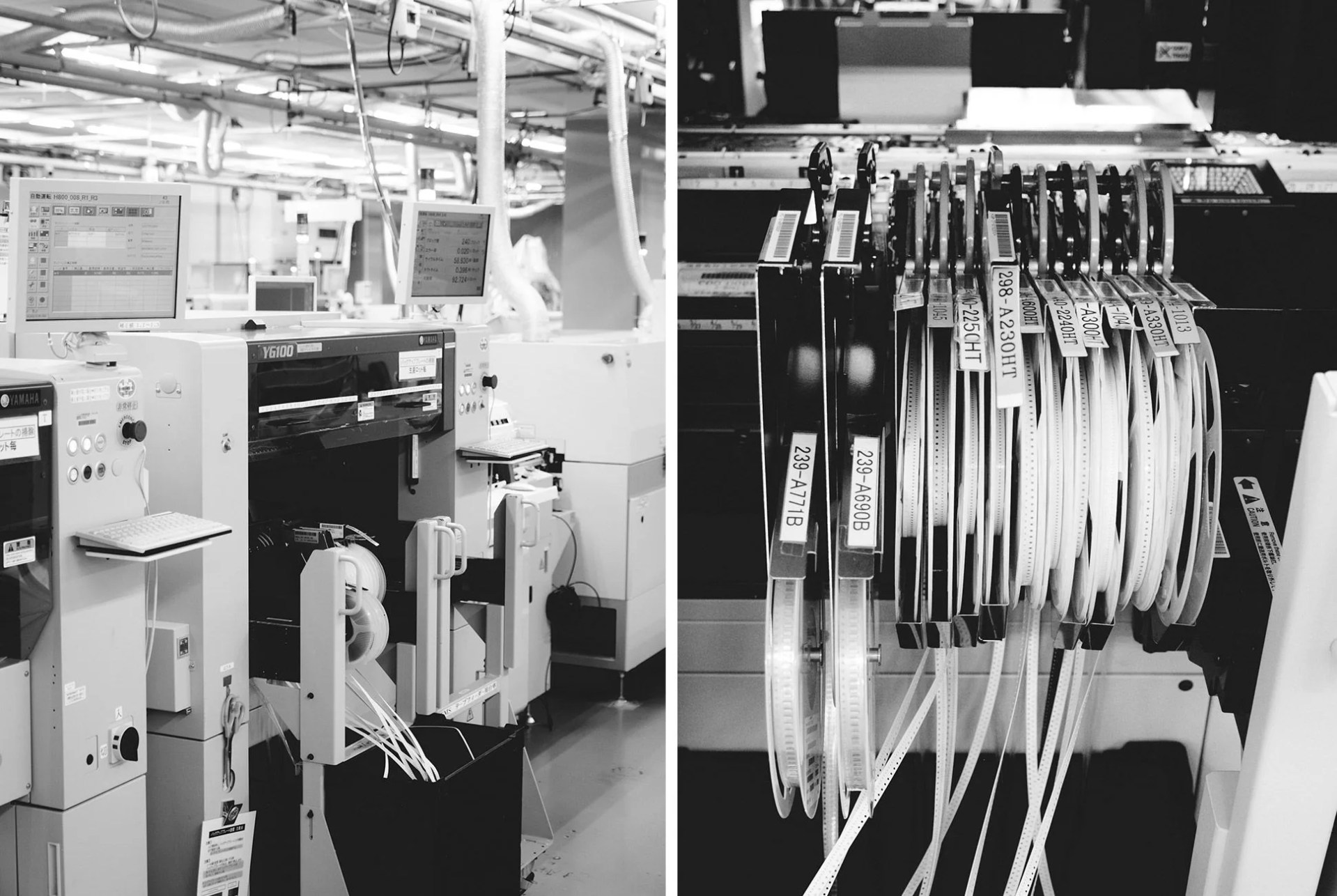

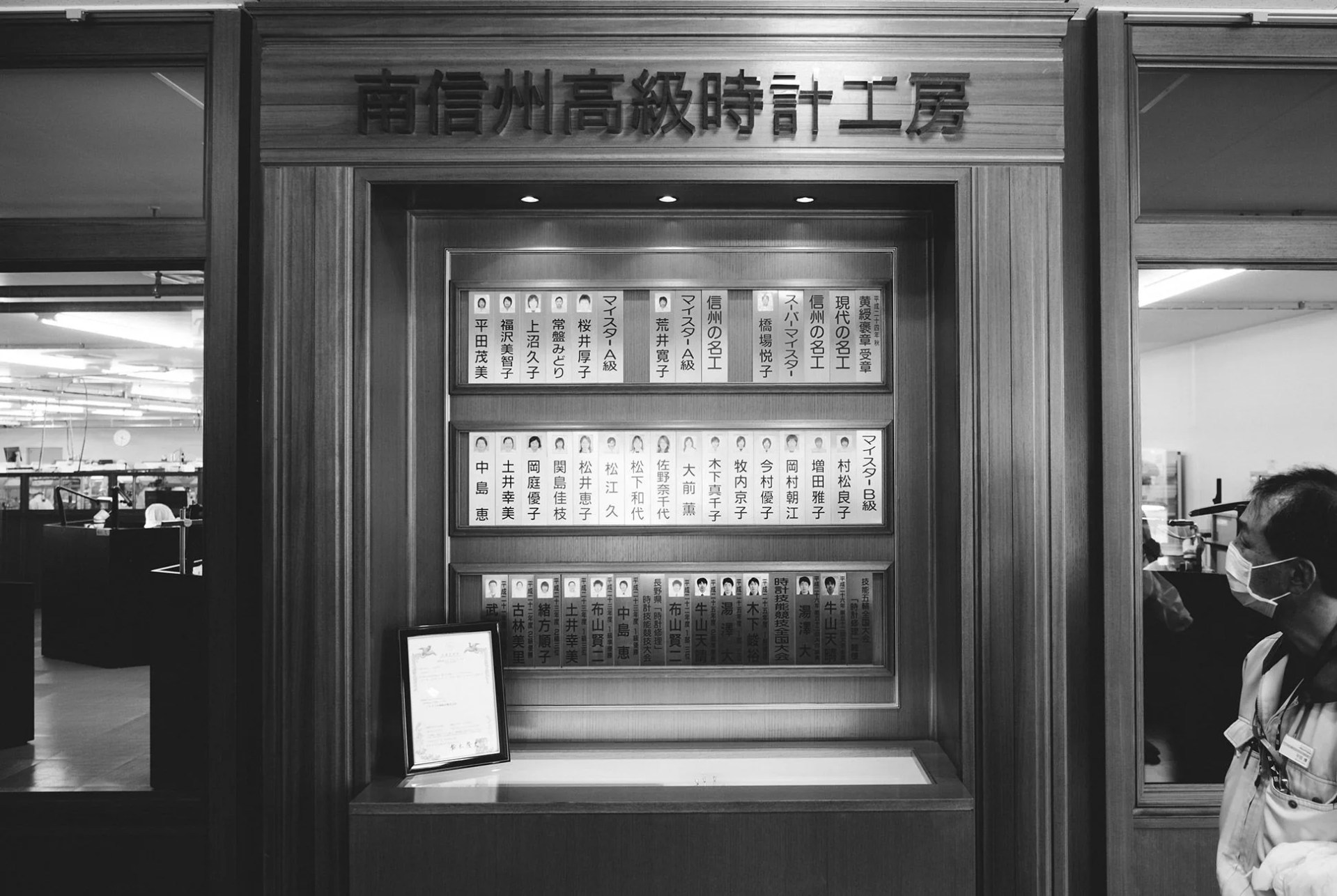

Citizen is, perhaps unsurprisingly, tight-lipped about how they accomplish the feats of the Eco-Drive One and their other watches. But earlier this year I was able to peek behind the curtain to glimpse their vast operation across Japan, which employs 20,000 people. There, the men and women behind Citizen’s dominance are evolving what a high-end timepiece can be.