The James Bond films are a 59-year, 25-film franchise that until relatively recently has been drowning in mediocrity. In an attempt to understand how such a study in averageness can breed a cultural phenomenon I’ve watched them all, watched them all again, watched the “edgy one” with George Lazenby, watched the new ones with Daniel Craig, even watched License to Kill twice — and License to Kill has all the intrigue and drama of Pauly Shore’s Bio-Dome.

I love the Bond franchise; I have ever since I first witnessed 007’s adventures on the big screen (it was Goldeneye — not the most auspicious start) and dove into the world of Aston Martin DB5s and shaken martinis. Then, this June I decided to finally read the books and explore the genesis of my favorite secret agent. Having just recently finished the 14-book series, all I can say is that it’s been a revelation and the James Bond we’ve been seeing on screen lately — moody, introspective, genuinely human — is getting closer and closer to Fleming’s original.

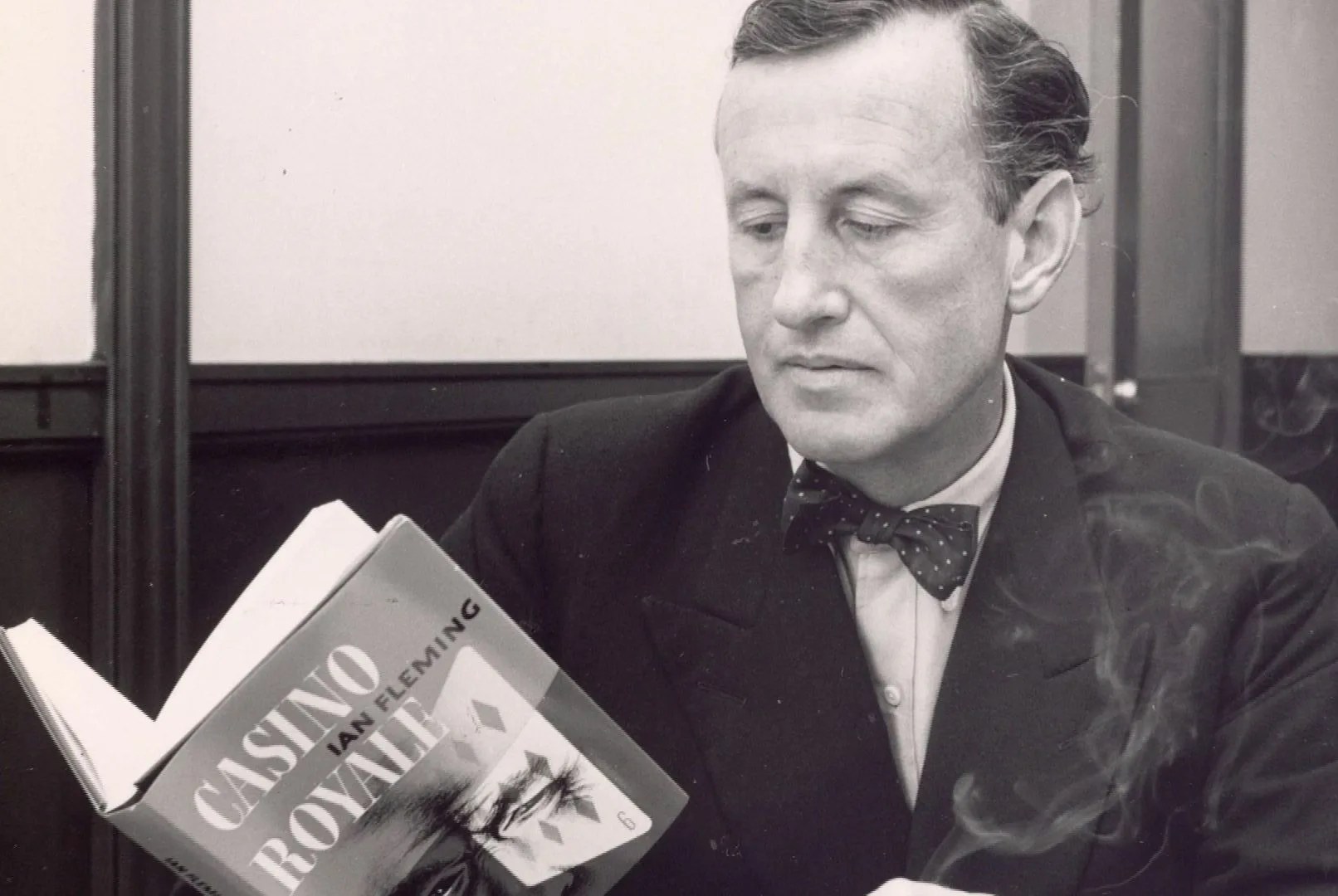

Astute readers will have realized that through a catchy title and compelling introduction you’ve been roped into another “The books are so much better than the movies” opinion piece — but this is a point worth making for those of you whose only experience with the British secret agent is through Connery, Moore, Craig or, god forbid, Brosnan. During his writing career, Ian Fleming produced 12 full-fledged Bond books beginning with Casino Royale in 1953 and ending with The Man With The Golden Gun, which was published in 1965, a year after Fleming succumbed to a heart attack. Along the way there were also two Bond short story collections (For Your Eyes Only and Octopussy and the Living Daylights), and he even took the time to pen Chitty Chitty Bang Bang for his only son.

It’s been a revelation and the James Bond we’ve been seeing on screen lately — moody, introspective, genuinely human — is getting closer and closer to Fleming’s original.

The books are incredible. Of course, From Russia With Love isn’t going to compete intellectually with The Brothers Karamazov, and it’s worth noting that, being a product of ’50s Britain, the books tend to have a not-subtle tinge of racism, misogyny and general insensitivity. But for what they are, for quick thrills and engrossing adventure, they’re unmatched. If there’s to be a Bond Dynasty (and at this point it’s safe to say there is), it would be a gross disservice to only remember Agent 007 from the films.

By way of illustration, in the opening of the one of the most critically acclaimed Bond films, 1964’s Goldfinger, Sean Connery infiltrates a Mexican drug laboratory using a grappling hook and a scuba mask inexplicably topped with a stuffed seagull. He then proceeds to set a bomb of plastic explosive, check his Rolex Submariner and change into a strapping white tux before the scene is set into chaos as the bomb explodes and Bond utters the phrase “At least they won’t be using heroin-flavored bananas to finance the revolution,” before killing another Mexican by throwing a space heater into a bathtub. We’re well outside the realm of subtlety here.