3 photos

Boyle’s Law states that as the volume of a gas decreases, its pressure increases. It is a well-known law of physics expressed as PV = k. Watchmaking involves many laws of physics; Boyle’s is not usually among them. But it is precisely this principle that Oris, the independent watch brand from Holstein, Switzerland, exploited in its groundbreaking Aquis Depth Gauge diving watch. In doing so, Oris exploited another important principle: making high-quality watches that more people can afford.

While watches with depth gauges are nothing new, they typically measure depth by mechanical means: water pressure acts on a membrane that then drives a geared needle to display the corresponding depth. These watches are predictably complicated and expensive. Oris, guided by its company slogan, “real watches for real people,” set out to create a more affordable alternative. The Aquis Depth Gauge allows water through an orifice in its extra-thick crystal, which compresses air in a narrow channel around the outside of the dial. The interface between water and compressed air in the channel lines up on a scale to show current depth like seeing water in a drinking straw. It is remarkably accurate, uses no moving parts, and is also far more affordable than its depth sensing counterparts.

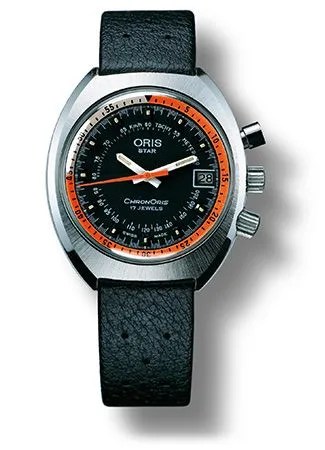

Oris was founded in 1904 on the principles of building watches for “the working man”. Contrary to the artisanal masterpieces being built by many other Swiss brands, Oris set out to make sturdy watches built on a large scale that could be sold affordably. Its watch factory near Holstein (the name “Oris” comes from a brook that flowed nearby) made use of the latest industrial techniques, while its designers sought to find simpler ways, compared to elaborate complications found in other brands’ timepieces, to add functions. One early example, for which Oris is now famous, is the “pointer date”, which used a central hand pointing to the date instead of the date being shown in a small window on the dial. A centrally mounted hand is a simpler solution than a date disc inside the watch — easier to build, more reliable and more affordable, traits it has in common with the Aquis Depth Gauge. Similarly, its striking orange-and-black Chronoris chronograph, introduced in 1970, featured only a central seconds sweep hand for timing events, while a rotating bezel was used for tracking elapsed minutes — another simple solution in lieu of a more complicated, and expensive, movement.

To many watch enthusiasts, a hallmark of a worthy brand is the use of purely “in-house” movements, those designed and manufactured under the company’s own roof and from the beginning, Oris was a leading manufacture that had over 400 unique calibres to its name. But then, as with so many other brands, it fell victim to the so-called Quartz Crisis in 1970 and was bought by the ASUAG holding company, which would later become the Swatch Group. Oris would languish under this umbrella until 1982, when the company itself, led by CEO Ulrich Herzog, bought its own independence. As part of the buyout agreement, Oris was required to buy all of its mechanical movements from ETA, the movement-making branch of the Swatch Group. Eschewing in-house development, Oris used outsourced ETA movements exclusively, adding its own complications and finishing them in house, rebuilding its reputation as an affordable yet high-quality Swiss marque despite not being a true manufacture.

In the past few years, Swatch Group, in a highly publicized move, announced that it would no longer sell ETA movements to brands outside of its own. This was a blow to many brands that relied on ETA, and an ironic one for Oris, given the stipulation of its 1982 buyout agreement which prevented it from returning to its manufacture status. It turned to Selitta, another third-party movement maker, for its base calibres, to which it would further adapt and refine itself. And in 2014, to commemorate its 110th year in business, Oris once again developed an in-house movement, the Calibre 110, a handwound powerhouse with a full 10 days of mainspring reserve when fully wound. While the Calibre 110 was a limited-edition movement, a year later, the serially produced Calibre 111, which added a date function, appeared. It was a milestone for Oris but also a return to its roots. And staying true to its company philosophy, the new ProPilot Calibre 111 costs less than $5,000, well below the price of most in-house movements.