Kanye West is a master of hype and king of promotion. At his Madison Square Garden event on February 11, a sold-out crowd witnessed the third season of his Yeezy clothing line and a cavalcade of celebrities before hearing 10 songs from his new album The Life of Pablo, directly from his laptop. Building up to the premiere, West blew up his Twitter feed, hinting at various collaborations, arguing with Wiz Khalifa about wavy music and repeatedly changing the album’s title. But the frenzy is over. The album is out for streaming on Tidal: 18 tracks that clock in at just under an hour and feature a roster of guest artists from Rihanna and Kendrick Lamar to Frank Ocean and the Weeknd.

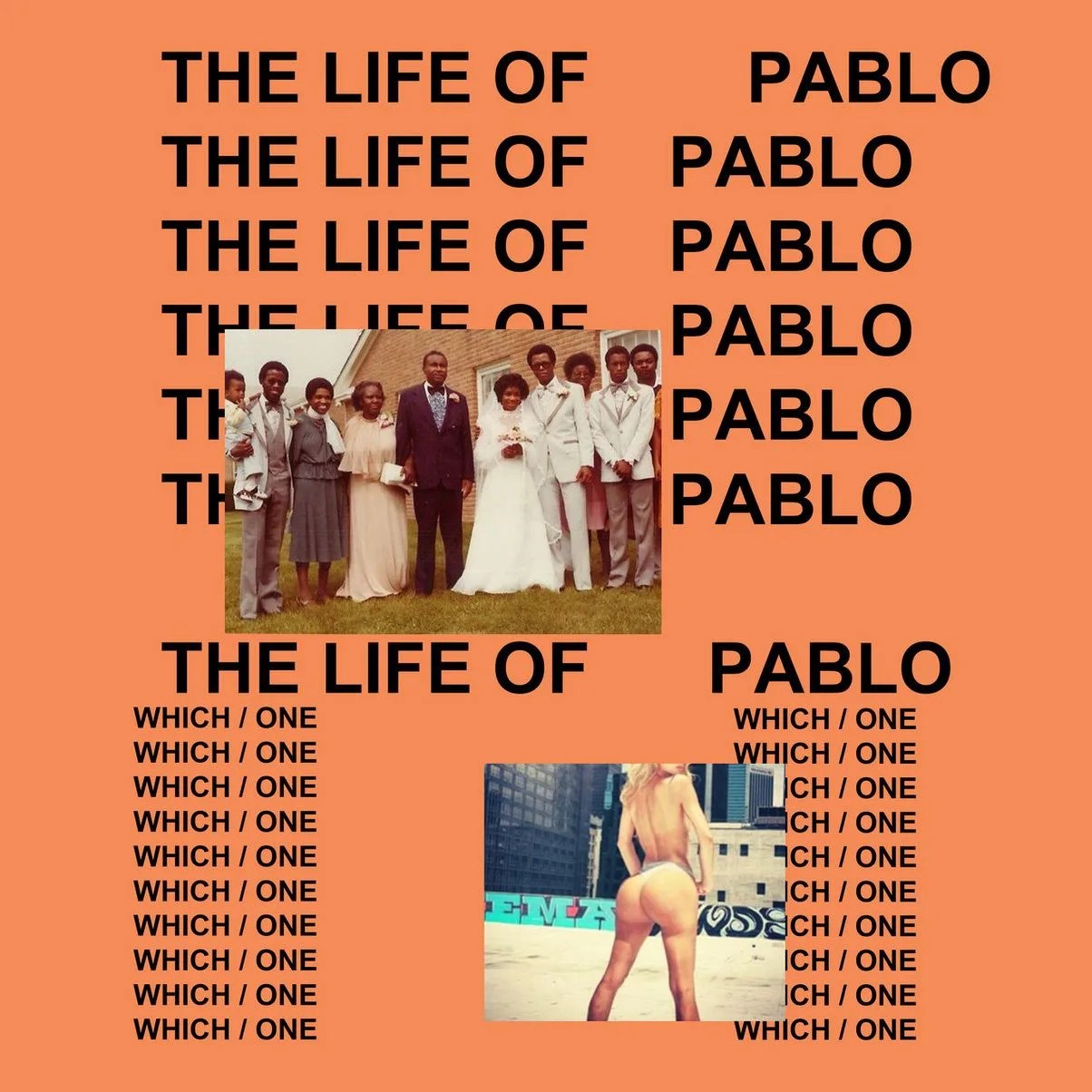

The hype-crazed West runs wild on the album, of course. But he’s tempered by another side. The album’s cover directly asks the question, “Which one?” — referring to either drug lord Pablo Escobar or iconoclastic 20th-century painter Pablo Picasso. This question resonates through the release, as strength and brutality counter with introspection and esoteric choices. Lyrics range from the sacred to the profane, and elements of gospel and electronica intermingle. Life of Pablo is a study in opposing forces, a postmodern approach to tension and resolution. Individual tracks sound, at times, disjointed, but the album as a whole achieves a cohesive balance of the real West.

Two forces at play throughout the release are the mind and the body — deep messages versus dick messages. The opening track, “Ultralight Beam,” deals with a relatable struggle; through the chorus a choir sings, “I’m trying to keep my faith, but I’m looking for more / Somewhere I can feel safe, and end my holy war.” But in the following track, “Father Stretch My Hands Pt.1,” West adds an element of stark crassness with a verse that begins, “Now if I fuck this model, and she just bleached her asshole / And I get bleach on my T-shirt, I’ma feel like an asshole.” The hyper-sexual lines reinforce the macho persona West has crafted for the media: he’s a kingpin and the lord of his domain. West uses “Famous” to assert the same persona when he raps, “I feel like me and Taylor might still have sex / Why? I made that bitch famous.” But later in the album, West slows down in “FML,” saying, “I’ve been thinking, about my vision / Pour out my feelings, revealing the layers to my soul.” This lyrical incongruity is not new to West’s music, though in The Life of Pablo, West distills the opposing elements of his persona into different tracks.

The songs, though dealing with opposites, work together to paint an aural picture of their creator with more clarity than ever before.

Contrasting musical elements are juxtaposed throughout the release, in a gritty cut-and-drop fashion, tying together elements of different African American musical styles. In “Low Lights,” lyrics soar over sparse, jazzy piano chords. But in a moment that could be nostalgic and cloying, he inserts a squelchy bass line and cameos one of early rap music’s keystone sounds. In the album’s hip-hop grail, “No More Parties in L.A.,” West trades verses with Kendrick Lamar against an interweaving backdrop. Yet the reimagined G-funk track starts with sampled lines from Junie Morrison’s 1976 funk tune “Suzie Thundertussy.” Though a gospel choir is included in the bookend tracks, swelling organ chords, calling to mind the flickering memory of a church, open the album, and pulsing house, Chicago’s own brand of dance music, brings it to a close. West compiles a century of music into one album, sometimes drastically cutting to a sample, other times layering a specific sound into the texture of a piece.

West makes frequent use of another classic instrument, lauded by legendary musicians from Miles Davis to Claude Debussy: silence. His use of space on the Life of Pablo from its outset — the measured organ chords of the first track, separated by short breaths of silence — can be jarring, but over the the course of the album it adds a sense of openness. In “FML,” an antiphonal intro pits West’s verse against short synth hits, the moments of quiet building the piece’s momentum. Endings and transitions in the album are abrupt at times, like changing channels on the TV. This is not without purpose, and many transitional moments happen towards the end of songs, creating a quasi-Golden Mean within the piece. The scat singing in “Famous,” the trap drums in “Freestyle 4” and the beat cutting out in “Fade” all happen at this moment, the ideal place for action in a piece of music.

The songs, though dealing with opposites, work together to paint an aural picture of their creator with more clarity than ever before. Amid the album’s lyrical peaks and valleys, the testosterone and ego in hip-hop are countered with existential thoughts — and the dichotomy points to what it means to be an artist in the genre right now, where pushing the genre forward must be tempered by a respect for the past. Most importantly, The Life of Pablo proves that Kanye — despite the Twitter rants, the “I’ma let you finish” faux pas, the bold unscripted statements — has the restraint of a genius to pair with the mania.