12 photos

Guitar builder Stephan Connor slowly walks along a secluded stretch of beach in southeastern Massachusetts — both his house and his workshop are located on Cape Cod. “There’s such an alien-like nature with the ocean,” he says, and his guitars reflect this curiosity with the sea — as well as his beach-combing hobby. Unique shells can be cut to decorate rosettes, bird bones exhibit ideal strength-to-weight ratios and scallop shapes inform new bracing patterns. “For me, I’m always thinking about guitars and new ideas to try out,” Connor says. “Going by the beach helps harmonize my soul.”

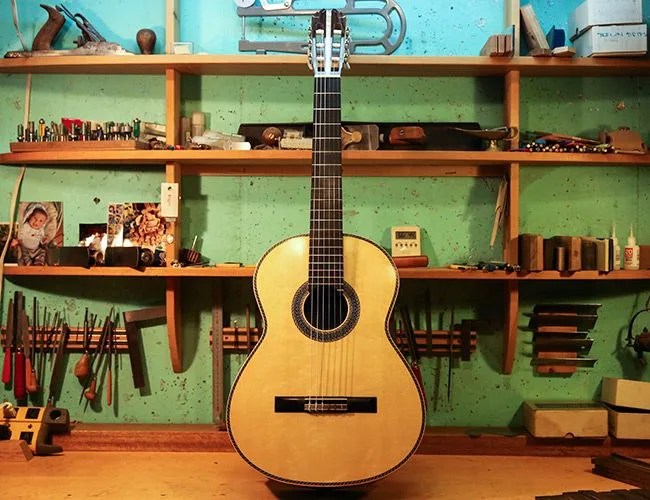

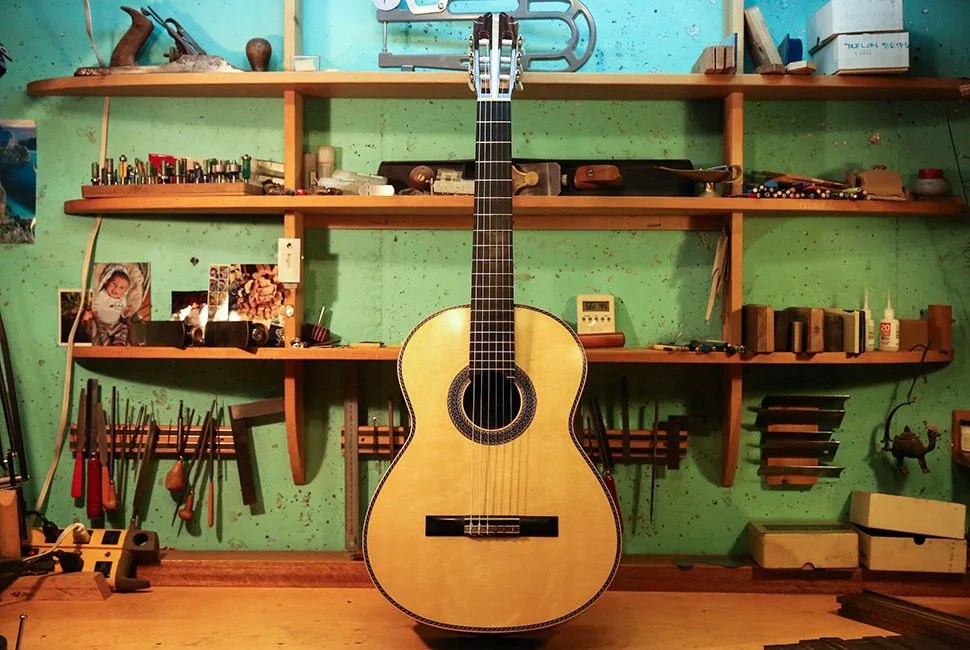

An early realization Connor had about cars later transferred to his guitar building: he loves German sports cars, and that love is centered around the precision of the performance engineering. But as the years passed, he yearned for more of a daily driver, with touches of flare and performance. His guitars, today, are similar to his automotive interests. They are beautiful, they have unrivaled playability, and they have a powerful yet nuanced sound. The instruments sound great un-amplified in small and mid-sized concert halls, and they have tonal subtleties that make them ideal for recording. Connor describes his house style as “an exuberant, punchy, rambunctious, strong sound,” and he focuses on “strong trebles, but with color and nuance,” so that melody lines in pieces of music will sing. His world-class instruments are played by the top classical virtuosi — the who’s-who of this sect.

They are beautiful, they have unrivaled playability, and they have a powerful yet nuanced sound.

Connor came to luthiery tangentially. He studied music history in college and his primary instrument was the guitar, but it was only after he was introduced to a guitar made by Manuel Velazquez that he realized the best classical guitars are actually made by individuals. In the following years, he went to woodworking school and, serendipitously, his hands seemed to take to it naturally. Connor notes, “There was a hand plane — I had never used one before — and I was like, ‘What’s this?’ But when I started using it, you’d think I’d found excalibur.”

For the first 50 guitars he made, Connor chose to survey the great makers of the past, trying to understand what made each special, hearing the sounds that reflected unique engineering equations. From the clear, disciplined sound of the German Hauser guitars to the flamboyant, boisterous qualities found in Spanish Ramirez instruments, Connor soaked up the great designs of the past while exploring aesthetic challenges like intricate binding and rosette work.

Not wanting to just reproduce historical copies, Connor’s modus operandi moved to experimentation in hopes of creating something valuable for the field. In 1993, after ruminating on ways for guitarists to better hear themselves, he drilled a hole in the side of a cheap guitar. The resulting instrument was better than he could’ve hoped: he had essentially created a personal monitor for the player (without a loss of sound quality). Around the same time, he also experimented with bracing patterns: traditional builders brace the soundboard of the guitar with a fan of five or seven braces, steel-string guitars are traditionally braced in an X-pattern and a popular Australian nylon-string builder was bracing in a lattice pattern made from graphite. Connor ended up with a three-by-three scalloped wooden X-brace. His 52nd instrument included both the iconoclastic sound port on the upper bout of the instrument and the new bracing pattern, a style of instrument he could continue to refine for the coming years.