24 photos

Strains of piano and voice drift through the walls of the Frank Music Company, New York City’s last remaining sheet music store, five blocks south of Central Park and ten stories straight up. Outside it is frigid and pouring snow, but in here 15 or so people warm the room with their body heat; in the musty air of the store’s cramped front area, it feels more like 50. The music filtering through the walls comes from the practice rooms that fill out the rest of the building’s 10th floor, an oasis of song in Midtown Manhattan. At the front desk, owner Heidi Rogers tells a joke about four violists and a lawyer to the waiting customers.

MORE MUSIC: Old Town Music Hall and its Mighty Wurlitzer Organ | Best Albums of 2014 | Photo Essay: Firefly Music Festival

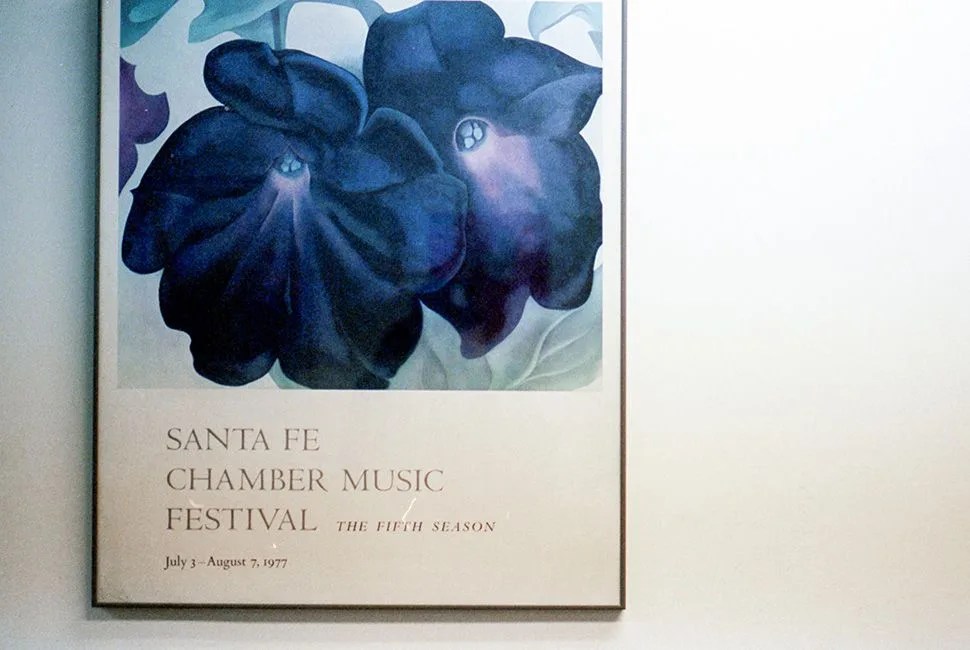

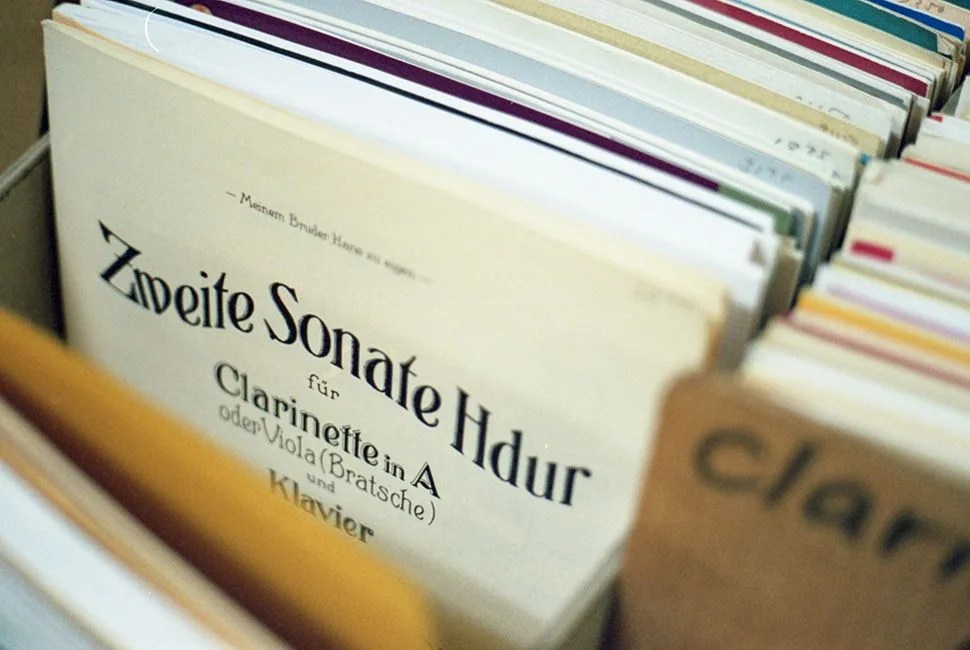

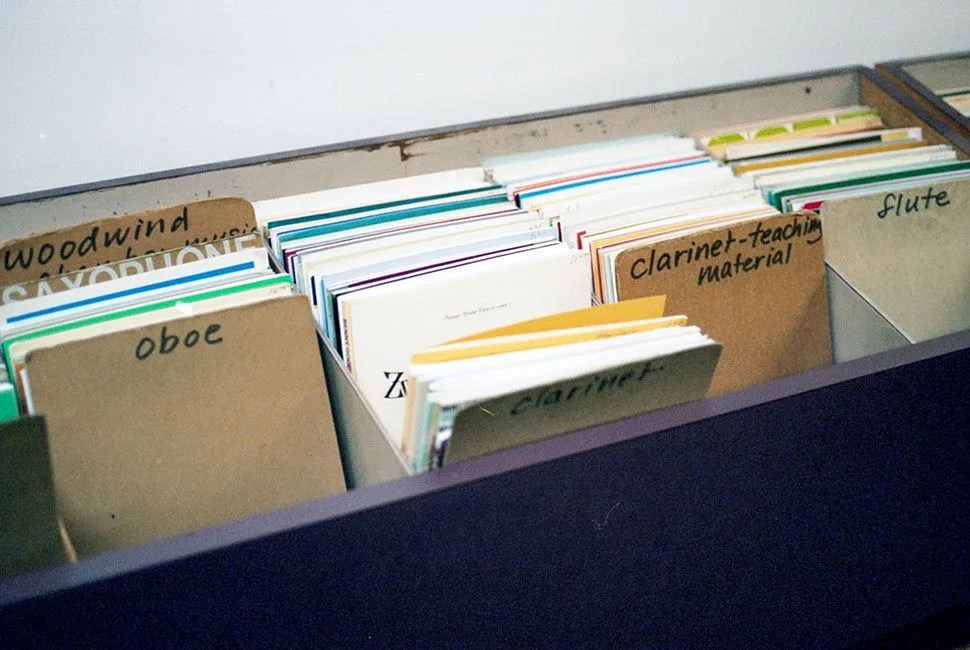

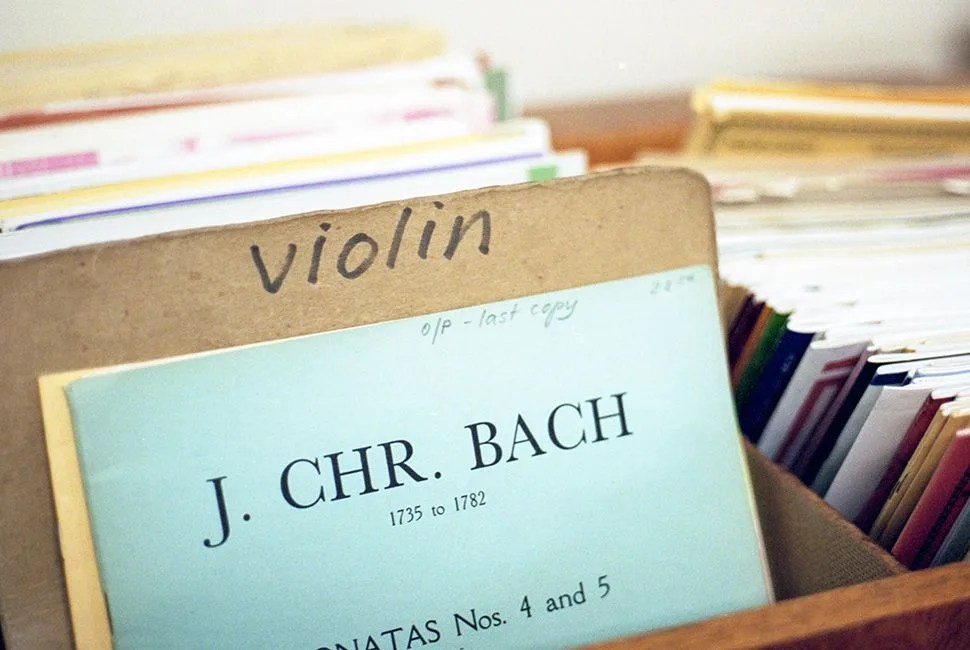

The front door, belled, rings every minute or so with a newcomer. They’ve have been showing up in droves since they heard the news. In the store’s small front vestibule, rows of boxes at hip height have been filled with music, separated by instrument. There is a poster of Itzhak Perlman, the famous violinist, on the wall. A corkboard with cards for flute, voice, piano and cello lessons and two of New York’s concert piano tuners hangs near the door. There are reminders everywhere, in posters and handwritten pleas, that photocopying music is a copyright infringement and is ethically and legally wrong.

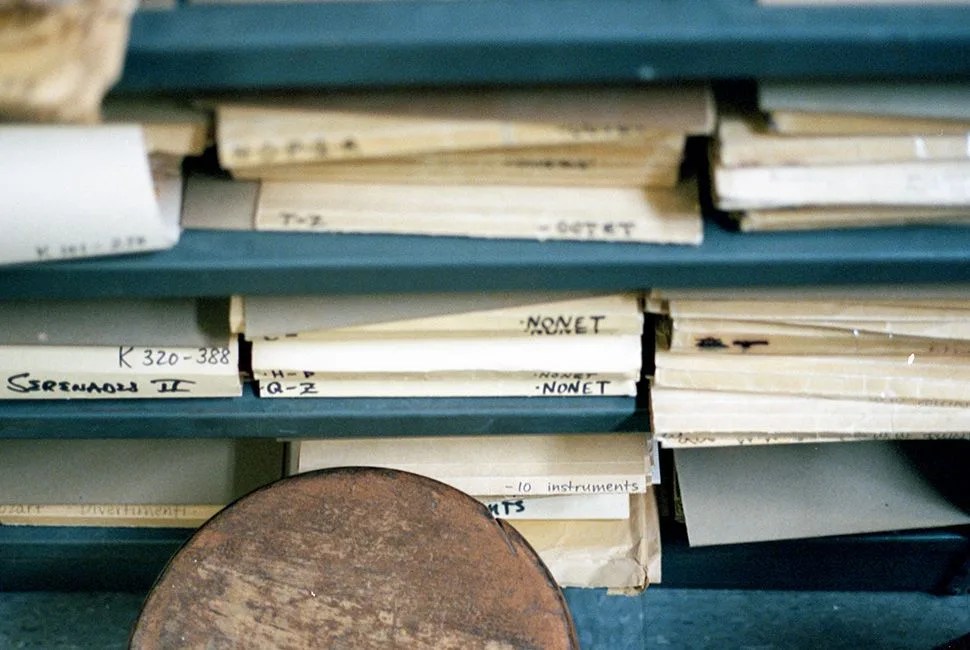

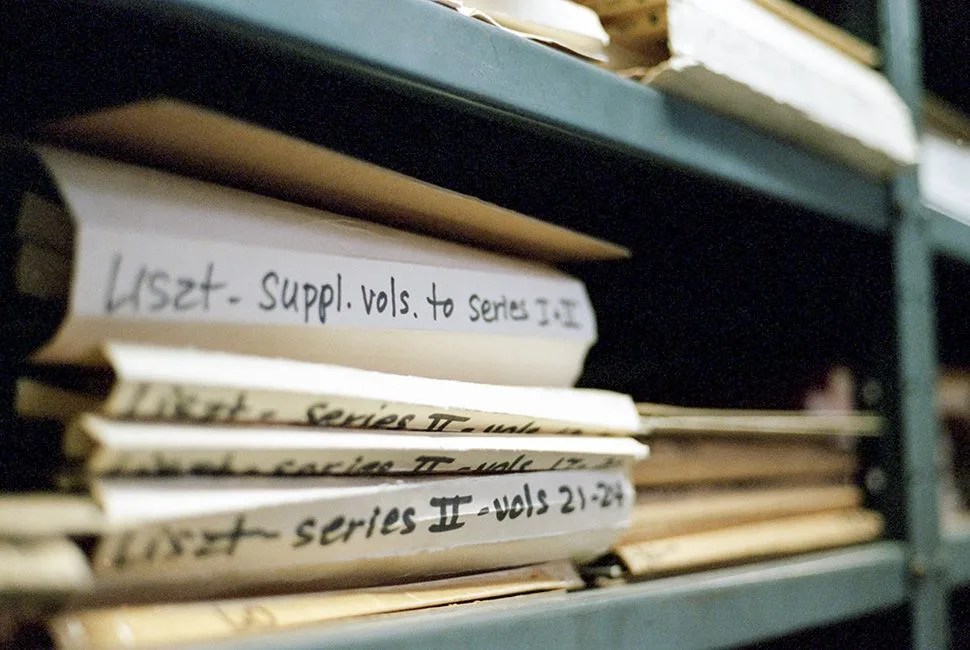

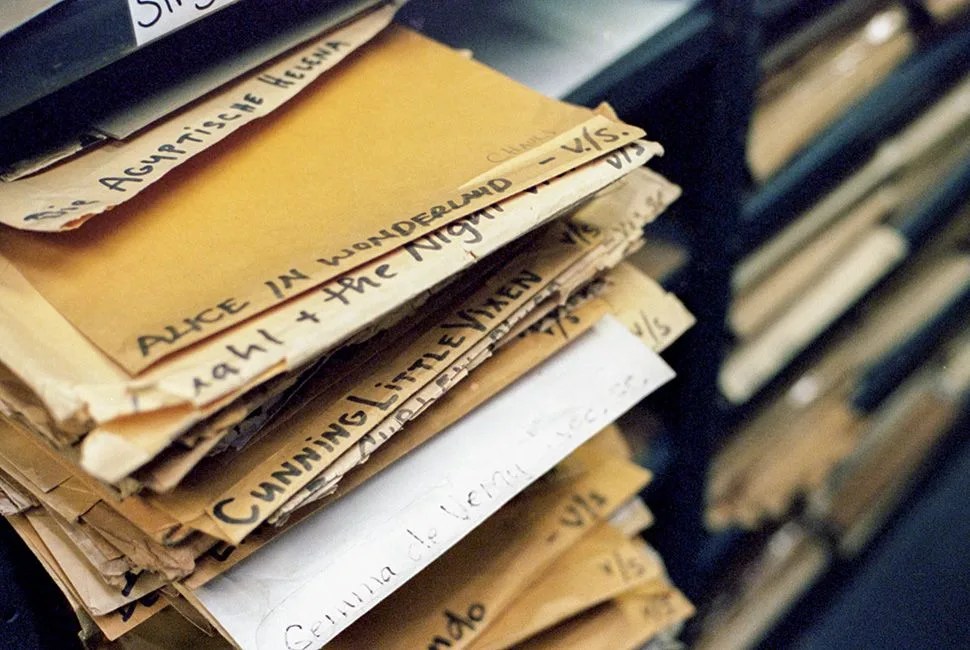

The second saddest mark of Heidi and Co’s failed campaign against photocopying, music pirating and the rise of music-buying online — that is, the store’s closure after 37 years of operation — looms eight feet tall behind the front counter where Heidi is chitchatting with customers. There, an ancient metal shelving unit stands packed with manilla folders marked in sharpie ink: Dvorjak. Beethoven. Mozart. Haydn. Britten. Shostakovich. Gershwin. Behind that metal shelving unit is another filled with many more names, then another. The loaded giants define the back section of the store, a comfortable, messy archive of the history of music, dotted with leather armchairs and old computers and printers, signs of long-lived business residence. The number of composers great and small in this tiny room, let alone individual pieces of music, boggles the mind. With the store’s closure, most of the music has been bought by an anonymous donor to be donated to the Colburn School, a music conservatory in Los Angeles. It will be around a long time, in one form or another, carrying on the legacy of these composers to future generations of musicians. Just not here.

“I’ve waited on 70 people today, which is more people than I’ve seen in five years,” Heidi explains to the waiting crowd. She sighs.

The saddest mark of the failed campaign, though, is Heidi Rogers, whose second-to-last day in her store is coming to a close. She’s owned the place since 1978, when she was 26. Hers is a tired sadness, buoyed constantly by a bright and easy sense of humor. Her customers aren’t made nervous or uncomfortable because she isn’t trying to hide it. She is sharing it with them.