Olympus’s new OM-D EM-1 ($1,400, body only) is way ahead of its time. Effectively an upgraded version of the already-capable E-M5, the E-M1 is an excellent shooter across the board, albeit one that can’t quite find its place in the market. We say: stay different, E-M1.

Though Micro Four Thirds cameras in the past have been small and aimed squarely at the consumer market, in the E-M1 Olympus has elevated the category to the pro level and increased both size and build quality. Our quick hands-on proved that the EM-1’s autofocus was the star of the show, having been greatly improved over the version in the E-M5; phase detection and contrast detection AF systems were quick and accurate in all sorts of light. Other notable improvements include a massive and vibrant electronic viewfinder, which hangs tough with many found on full-frame DSLRs, and a new 16MP sensor and image processor.

Does Size Matter?

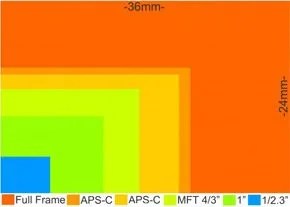

Sensor size in digital cameras is a hotly debated issue that most people have a hard time articulating. Simply, the sensor is the part of the camera that records the image and translates incoming light into data that can be read by a camera.

Of two differently sized sensors with the same resolution, the bigger sensor will devote more area of the sensor per pixel and allow for better dynamic range, less noise and better low-light performance. Bigger sensors also tend to allow for shallower depth of field and higher resolution photos. The downsides to going big? Expect to pay more and carry a bigger camera.

Several highlights of the E-M5 have been enhanced slightly on the new flagship, like improved freeze-proofing of the weather sealing and a 5-axis in-body stabilization that automatically detects things like panning shots; of course, Olympus’s fleet of lenses continues to get better. All of these details are concealed inside a new magnesium-alloy body with a bigger, more comfortable grip. Though it has the reassuring heft of a DSLR, in size it’s still relatively minute — comparable to a Canon Rebel SL1.