At the most basic level, all camera lenses can be sorted into two groups: zooms and primes. Zoom lenses do just what you think, twist a ring (or hit a button) and they zoom in or out, changing how much of the scene you see. Prime lenses, on the other hand, are fixed, unable to zoom in or out, and just display one set level of magnification.

You might be thinking “Well, it sounds like I should just get a zoom lens for the added flexibility,” but that would be false. Or at least mostly false. To be sure, some zooms rule, lenses like Canon’s 28-70 f/2 and Nikon’s 70-200 f/2.8 are wonders of optical engineering, but they’re also absurdly expensive, absurdly heavy and absurdly big.

Prime lenses, on the other hand, are relatively simple. There are no complex helicoids and significantly fewer glass elements, so this means that primes can be cheaper, lighter, and better — all at the same time. To get 50mm at f/2 with that Canon zoom above will cost you $3,000, to get 50mm at f/2 with a Canon prime will cost you $150. The image quality will be basically indistinguishable. That’s insane.

To avoid getting further worked up about how great of a deal prime lenses are, I’ll summarize: the absolute best quality-per-dollar investment you can make into any camera system is a prime lens, but which one?

A Quick Primer on “35mm Equivalent”

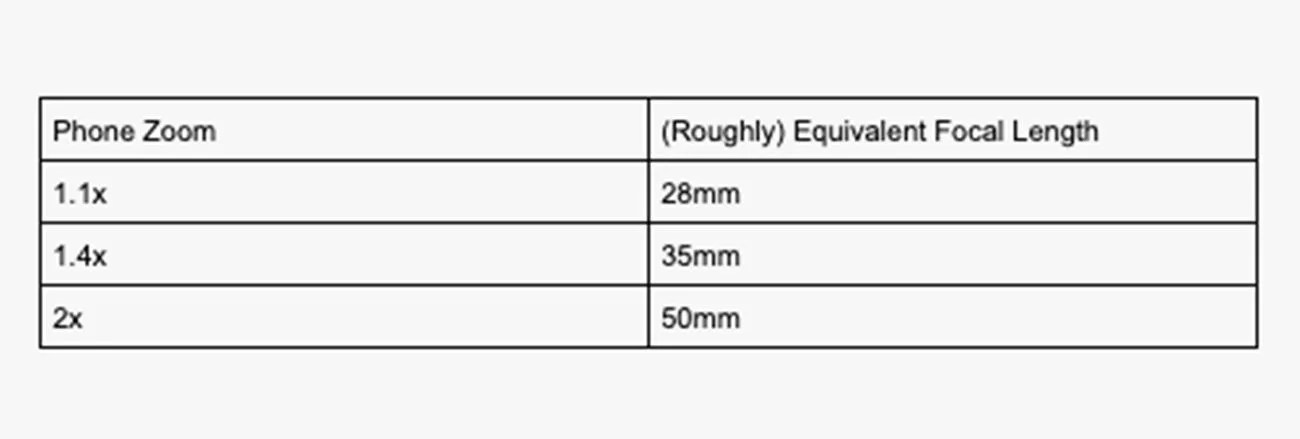

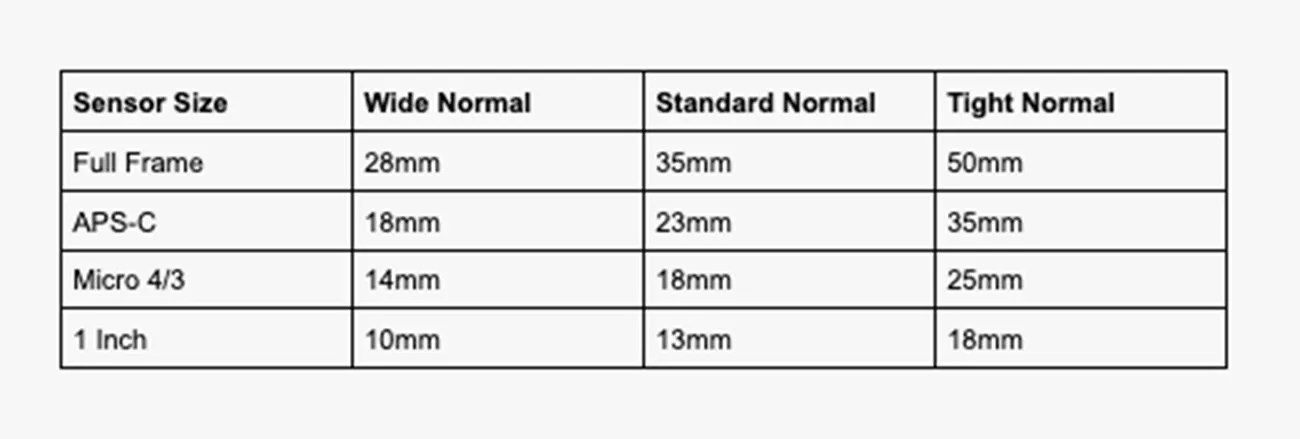

The idea of “35mm” or “full frame” equivalent is needlessly confusing and annoying, but it’s really the only way to talk about similar shooting experiences over cameras with different sensor sizes. You’ll sometimes see this referred to as “crop factor”. So, a quick table of lenses that will provide (nearly) the same shooting experience, depending on your camera’s sensor size:

Courtesy

Courtesy