From Issue Four of Gear Patrol Magazine.

Discounted domestic shipping + 15% off in the GP store for new subscribers.

On the banks of the East River sat an industrial park with the charm of an elephant graveyard — remote and vacant, inhabited only by dilapidated warehouses, the skeleton of a once-thriving ecosystem. In this park, during the Second World War, 70,000 men and women built the most impressive battleships in the world. When the war ended, however, so did the need for warships. And as the Manhattan skyscrapers across the river continued to stretch higher, the Brooklyn Navy Yard withered in their shadows.

The 300-acre industrial park was decommissioned in 1966, and over the next few decades the city tried unsuccessfully to breathe new life into the area. Then, in 2009, the Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation (BNYDC), a nonprofit initiative, set out to make the Yard an eco-friendly industrial park — a national model for green technology and sustainability.

The Yard is now in the midst of a $700 million redevelopment. Non-shipbuilding businesses are moving into renovated historic buildings alongside gleaming new ones. There’s a movie production studio, Steiner Studios; a chocolate maker, Mast Brothers; a military armor and apparel company, Crye Precision; and a coffee roaster, Brooklyn Roasting Company. All are joining in with the revitalization plan, and some have already moved in. One neighbor to these tenants is a groundbreaking tech venture, New Lab — an innovative 84,000-square-foot space dedicated to helping tech companies manufacture hardware.

Long gone are the shipbuilding machines; it’s now filled with glass offices, colorful lounges, exotic plants, communal worktables and prototyping workshops.

The New Lab vision started in 2011, when David Belt first visited Navy Yard Building 128. The building had been abandoned for the previous 20 years and was in complete disarray — structure covered in rust and missing large swaths of the roof. “The idea that we could save it and make it something really special was important to me,” Belt said. “This was the center of state-of-the-art manufacturing when it was built. But what is state-of-the-art manufacturing today?”

The short answer: tech.

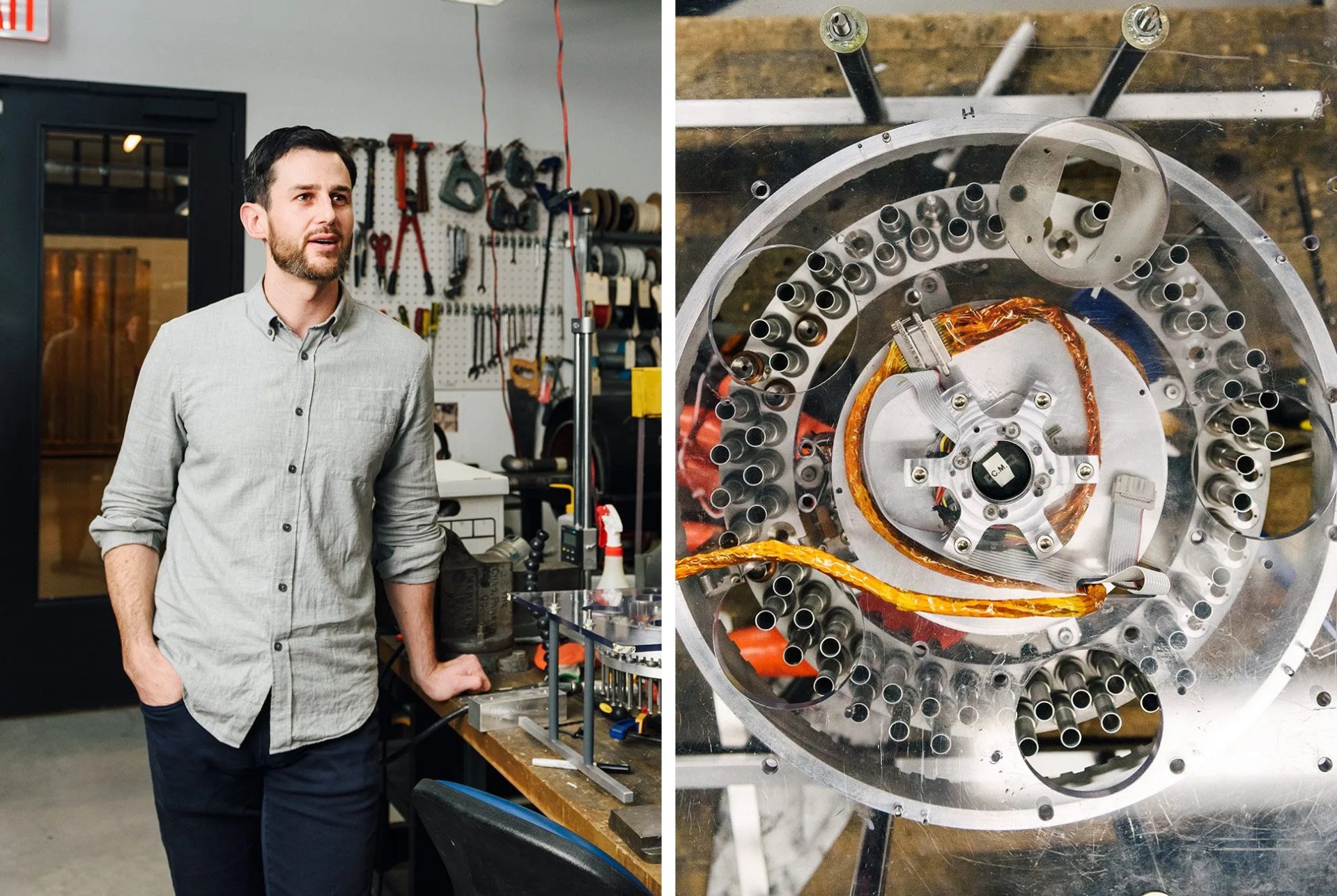

New Lab officially opened in the summer of 2016. The space is designed to help companies working on advanced technologies (robotics, AI, connected devices, energy and nanotechnology) by giving them access to millions of dollars’ worth of prototyping equipment, such as 3D printers, laser cutters, CNC milling machines and fully stocked wood and metal shops. Similar resources can be found at universities, as with MIT’s Media Lab, or at corporations, like BMW’s iVentures. But New Lab’s mix of independent companies makes it the only tech center of its kind in America.

Inside, the building retains the grandiose, industrial feel of its 1902 provenance. Nine thousand tons of steel course throughout the space’s cathedral-like trusswork with suspended bridges and gigantic cranes as doorways. Long gone are the shipbuilding machines; it’s now filled with glass offices, colorful lounges, exotic plants, communal worktables and prototyping workshops. “We didn’t want it to look like a typical tech space,” Belt said. “We decided that we didn’t know what the future was going to look like, but we did know what it looked like in 1973. That early-seventies optimism played a big role in the colors we picked, the furniture vernacular and the way we used the steel and glass.”

4 photos

New Lab functions like a shared workspace, but it’s a far cry from a WeWork. All the companies working at New Lab have a product with some funding. “They are not brand-new startups,” Belt said. “We’re not an incubator.” There’s a stringent application process; less than 20 percent of applicants are accepted.

As of February 2017, New Lab had over 70 companies and a total workforce of just under 400 people, with room for 500 total. The Navy Yard as a whole is projected to employ well over 300 businesses and a workforce of more than 10,000. Tech is a major part of this growth. “As a New Yorker, I feel like we play a role in tech that Silicon Valley can’t play — a very humanistic role,” Belt said. “We have diversity, density and issues around a whole bunch of urban problems that they just don’t have. So I really wanted to see a place like this in New York.”

On New Lab’s second floor, in a spacious corner office with a brick facade and a punching bag hanging from the ceiling, there’s StrongArm Technologies. The company builds passive exoskeletons — dubbed ErgoSkeletons — designed to protect industrial workers from lumbar (lower back) injuries. For a visual, picture a dialed-back version of what Matt Damon wears in Elysium. When a worker lifts something heavy, the ErgoSkeleton redistributes weight away from weak muscles to the legs and core, and the hardware can help teach workers proper body mechanics. “There’s a massive challenge with two-hundred fifty billion dollars in direct and indirect costs spent every year on worker-related injuries,” said Matthew Norcia, CMO of StrongArm Technologies. “Ninety billion of that is directly related to back injury. And for whatever reason, it’s never really been effectively addressed.”

StrongArm Technologies also builds connected sensors that, when working in tandem with a proprietary machine-learning algorithm and software, track and evaluate workers’ movement. The sensors deliver haptic feedback (a buzz) when they identify factors that will likely contribute to injury. “So, you’re wearing a device and you’re on a forklift,” Norcia said. “I’m about to walk out from behind the wall. I’ll get buzzed and your forklift will get stopped so we can prevent collision. It’s pretty fucking cool.”

Working in New Lab comes with several benefits for StrongArm Technologies. “The most important thing is that any idea we come up with, we can build here — and build it quickly,” Norcia noted. “There’s a pretty extensive set of labs and great access to equipment and machinery that we would otherwise, as a startup, not be able to afford or access.”

Then there’s the collaboration benefit. “There’s a level of expertise here that you don’t necessarily find in another location,” Norcia said. For instance, material scientists from other companies in New Lab contributed to the construction of a harness strong enough to hold StrongArm Technology’s FUSE sensor. Considering that tens of thousands of industrial workers at TSA, UPS and FedEx could wear such a harness, improving their health while also making a big dent in the $50 billion spent annually by industrial companies to compensate lifting-related injuries, it’s a significant collaboration. Thanks to New Lab’s facilities and community, those kinds of developments are part of just another day on the job.

Waverly Labs‘ goal is to change the way people communicate, forever. After one of the most successful tech Indiegogo campaigns ever, raising over $4 million, the company is now gearing up to ship its maiden product, named Pilot, this summer. The product looks similar to completely wireless earbuds, like Samsung’s Gear IconX or Apple’s AirPods, but it’s more adept. In addition to streaming music, Pilot is the world’s first translating earpiece.

“The original idea was to be the traveling professional’s earpiece,” said Andrew Ochoa, CEO of Waverly Labs. “I can use it for wireless music streaming, but if I end up in a conversation with someone who speaks a different language, I can hand them an earpiece, set it into translation mode over the app, and we can converse.”

Out of the box, Pilot will translate latinate and romance languages like French, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish and English. Translation occurs when two people each wear a Pilot earpiece, and talk (the smartphone app can also be used as an “earpiece”). Waverly Labs will be updating the firmware as the company grows, adding other languages from regions in Asia, the Middle East and Africa, and hopefully offering total verbal translation — no second earpiece or app needed.

The two biggest challenges Pilot faces are speed (how quickly the earpieces translate the conversation) and accuracy (how acutely it translates what the person is saying). Any lag can kill the flow of conversation, and if it’s not accurate, it’s obviously not functional. Pilot’s firmware uses machine-learning techniques so the latency and accuracy — which Ochoa ensured was already good — will improve over time.

Waverly Labs launched its first prototype on Indiegogo in 2016, but it needed a lot of refining. New Lab was the perfect place for this progression to occur, because it allowed the company to rapidly fine-tune prototypes. “We try to come up with a new prototype every week. Whether it’s a change in design or fine tuning something as simple as millimeters of fit to make it comfortable in your ear,” Ochoa said. “Having a 3D-printing lab space or engineering lab space down there makes it a really powerful building to work in.”

Pilot earpieces are expected to start shipping in late summer 2017. Over 22,000 units have already been preordered. The earpieces will cost less than Bose’s QC35s and come in an AirPod-esque case to negate battery worries. And they have the potential to change travel, business and communication at large. Not bad for an earpiece.

Far from a startup, Honeybee Robotics is a 30-year-old company that builds custom robotic systems for NASA and the Department of Defense as well as for private companies. The company works on a wide range of projects — such as building minimally invasive laparoscopic surgical and neurosurgical robots, drills and other equipment for planetary exploration on Mars, Venus and the Moon, and miniature pipe-navigation robots to inspect natural gas transmission lines.

“We were looking for an industrial space where we could spread out and make a bunch of noise — there aren’t many spots like that in New York,” said John Abrashkin, head of marketing and business development. New Lab’s shared prototyping facilities were also a big draw. When they wanted to test the miniature pipe-navigation robot, Abrashkin explained, they ended up hand sculpting a 3D replica of the pipe section, casting it in concrete and then testing the robot. The testing progressed quickly thanks to New Lab’s manufacturing equipment.

Honeybee Robotics also makes full use of the collaborations possible between New Lab occupants. This can be as informal as people troubleshooting project conundrums over coffee, or as formal as subcontracting for engineering services or prototyping help. “It’s like this huge brain trust that you can tap into,” Abrashkin said. “Our engineering team here is about fifteen people. They’re really good at what they do, but we have big blind spots. So we can fill that with people who know what they’re doing here, and then, likewise, they can come and ask us about things that we have expertise in. It creates a big virtual community.”

As a company that has made tools and drills for the last three Mars Rovers, Honeybee Robotics brings its fair share of brain power to the equation. While they continue to learn from those around them, it never hurts for fresh tech blood to consult with a company whose products have landed on the moon.