Without elevators, cities wouldn’t exist as they do today. And without safety elevators, most people would never get on one. The first safety elevator — which, in the event of the cable breaking, prevents the car from falling by automatically catching said cable — was engineered by an American named Elisha Otis, and despite the clairvoyant importance of his invention, it was a hard sell in the mid-1800s. The below excerpt, titled “‘All Safe, Ladies and Gentlemen, All Safe’: Mr Otis’s Safety Elevator,” is taken from America the Ingenious: How a Nation of Dreamers, Immigrants, and Tinkerers Changed the World, and tells the short story of Elisha Graves Otis’s life, and his many inventions, including the one that ultimately led him to awe audiences at the world’s fair with his up-and-down machine.

— Tucker Bowe

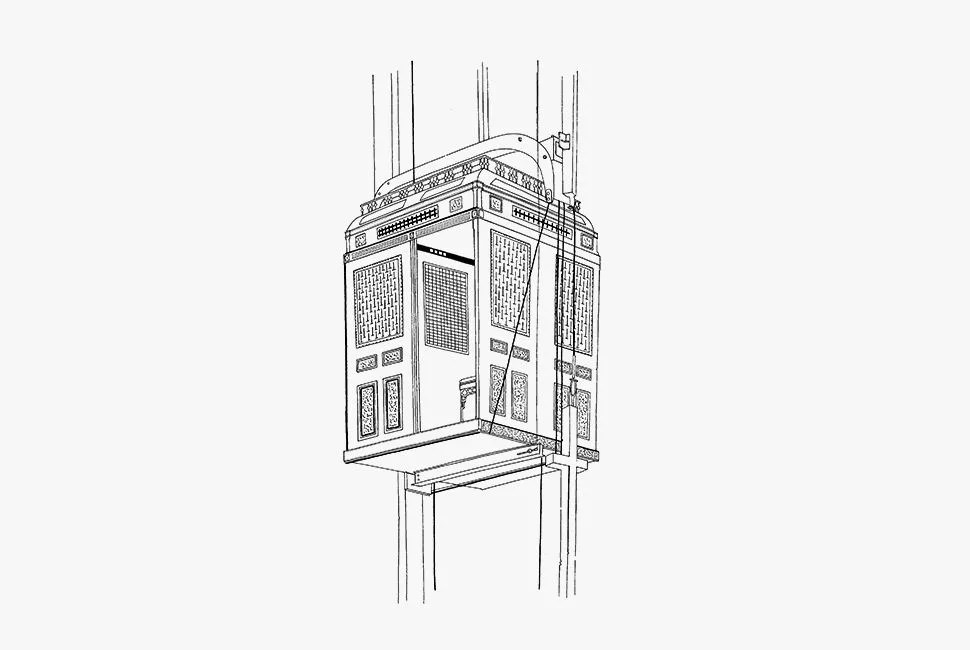

Editor’s Note: The following excerpt is from America the Ingenious by Kevin Baker (Artisan Books). Copyright ©2016. Illustrations by Chris Dent. The book is due out this October.

Sometimes it’s the little things, the things we barely notice, that make much greater accomplishments possible. Combined, as it would be in the next generation, with those two other miraculous American inventions — the electric light and steel-frame construction — the safety elevator would make the skyscraper, and thus the modern city, possible. All thanks to one man’s enduring faith.

He was, in many ways, the American Job, though many a frustrated inventor might have claimed the title. Like Job, Elisha Graves Otis was a pious, industrious man, respected by his friends and neighbors in rural Vermont; they would make him justice of the peace and elect him to the state legislature four times. He had left high school before graduating, as most Americans did in 1830, but, as his son would write, he “had no taste for a farmer’s life.” He drove a wagon instead, then started a gristmill, married a local young woman and had two sons with her, and built them all a house.

Then God started to test him, or so it must have seemed. The gristmill failed. Elisha turned it into a sawmill, but that failed, too. His wife died, leaving him with boys ages seven and two. Working in the bitter cold to make ends meet, Otis caught pneumonia and nearly perished as well. He married again and moved to Albany, New York, where he went to work in a bedstead company and invented a machine for turning out bed rails (sides) that enabled the company to increase its production from twelve beds a day to fifty. Rewarded with a $500 bonus, Otis started his own bedstead company, using a water-powered turbine he invented himself. Then the city of Albany diverted his water source, and his factory died. He tried to manufacture wooden carts, but that enterprise failed, too.

Freight elevators had existed since ancient times. Louis XV had even had a “flying chair” installed at Versailles, and steam-powered hoists, invented in England in the 1830s, were a common sight in America.

He invented a rotating, automatic bread oven; a steam plow; a new brake to let engineers stop locomotives faster. If one thing didn’t work out, Elisha Otis remained mystifyingly confident something else would.