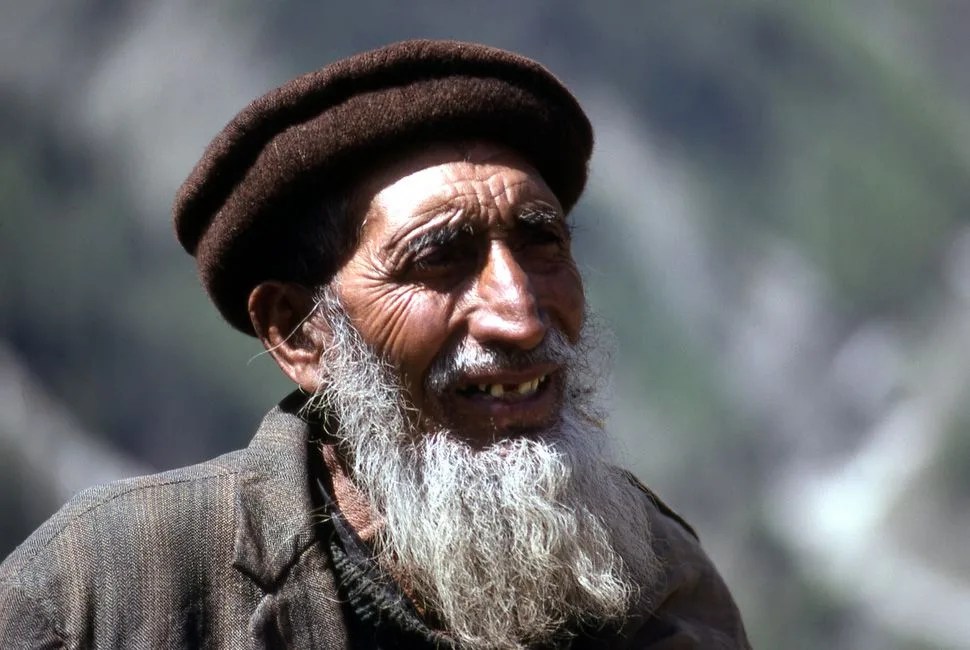

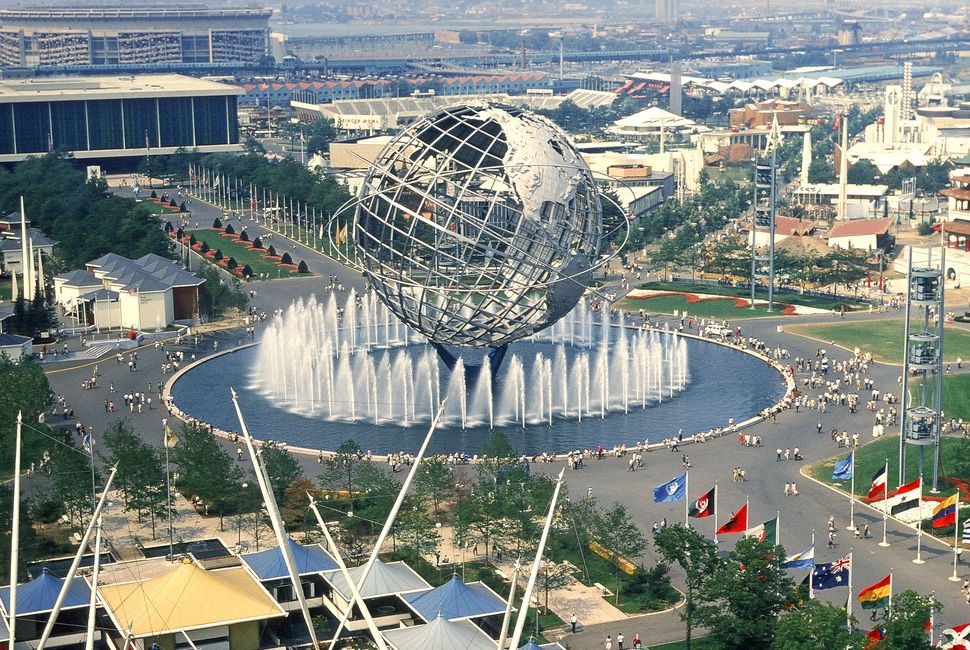

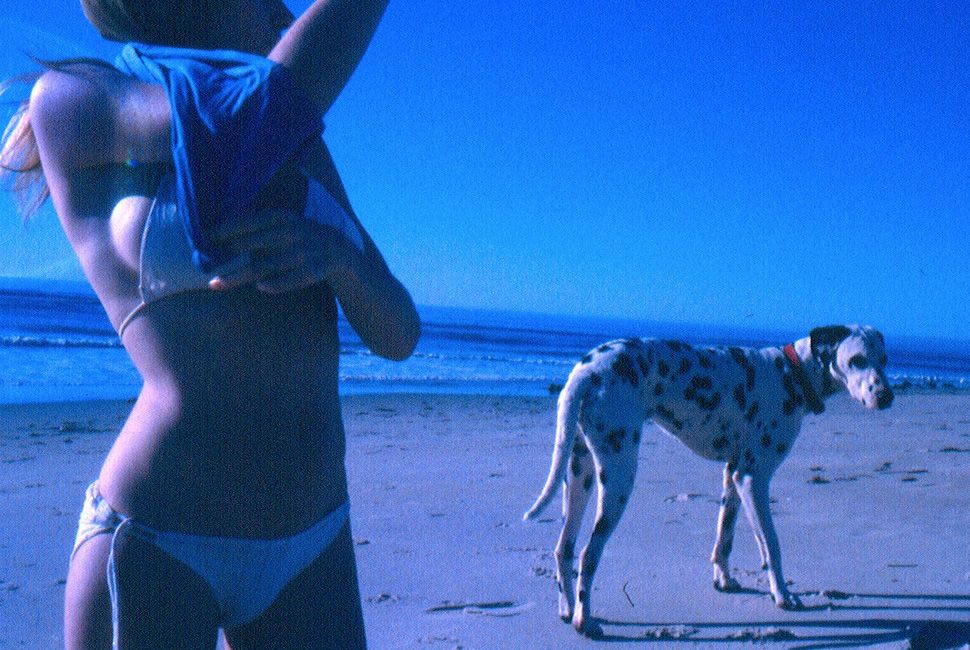

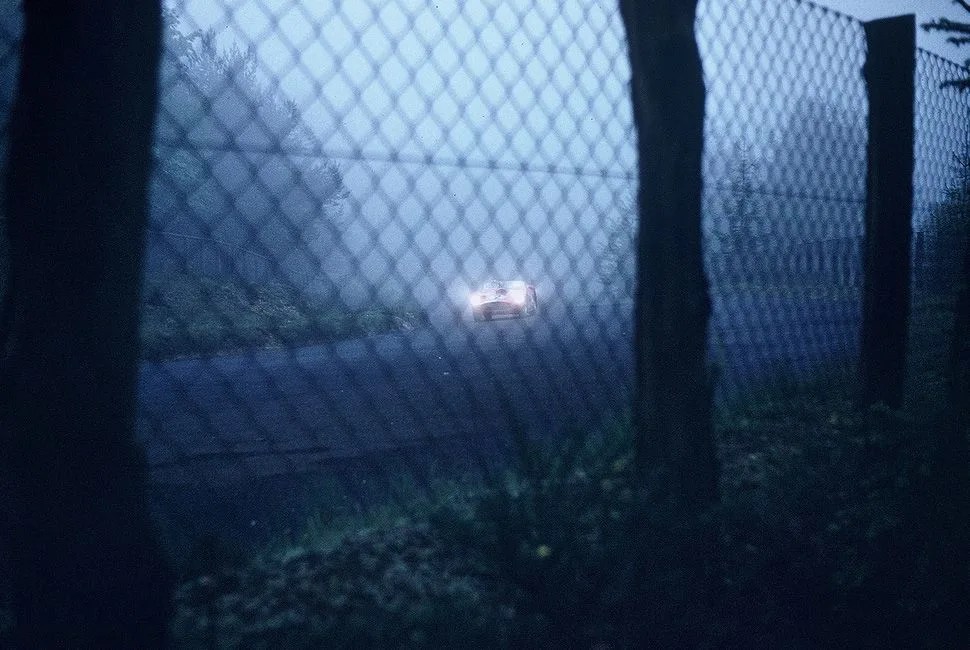

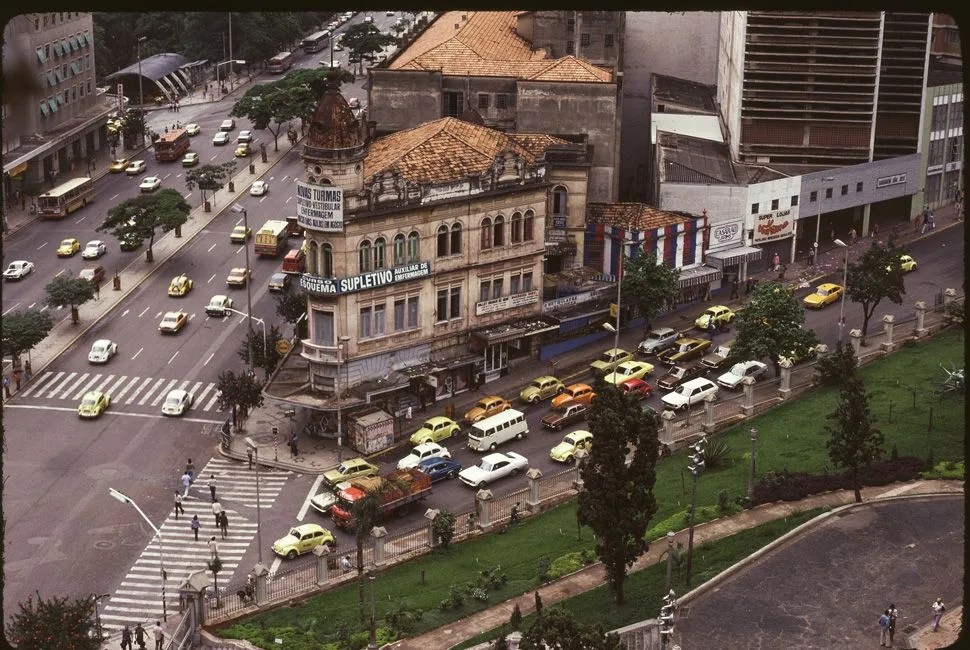

In June 2009, the Eastman Kodak Company publicly announced that it would no longer manufacture Kodachrome 64, its oldest and most iconic color film stock. It was a significant blow to the global photographic community, one whose effects were largely symbolic. The film had achieved a cult status among photographers — both amateur and professional — since its introduction in 1935, and had captured some of history’s most storied color photographs: William Eggleston’s “The Red Ceiling”, Steve McCurray’s NatGeo cover photograph of an Afghan girl.

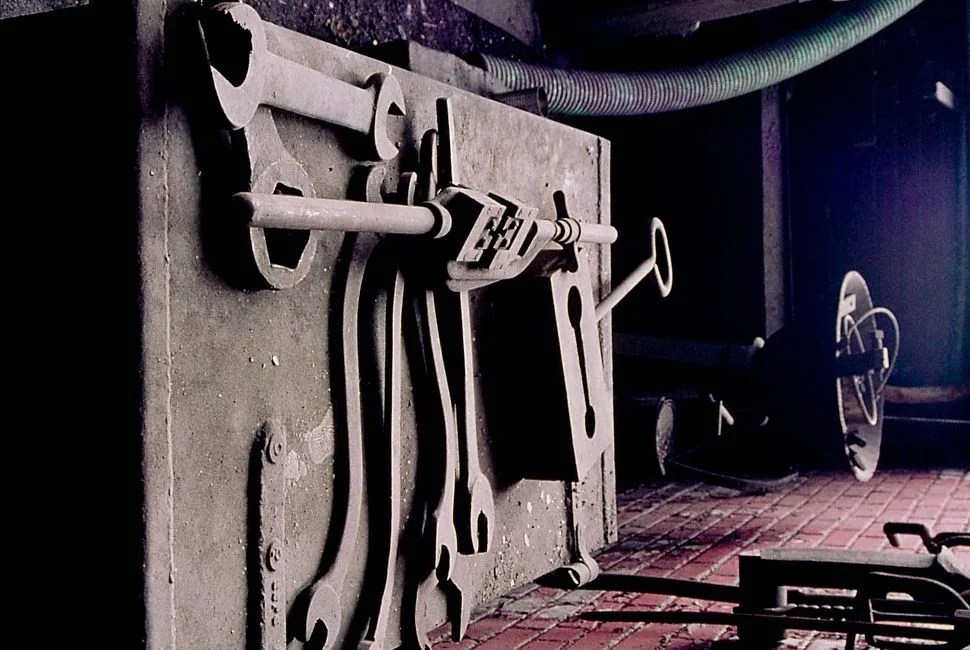

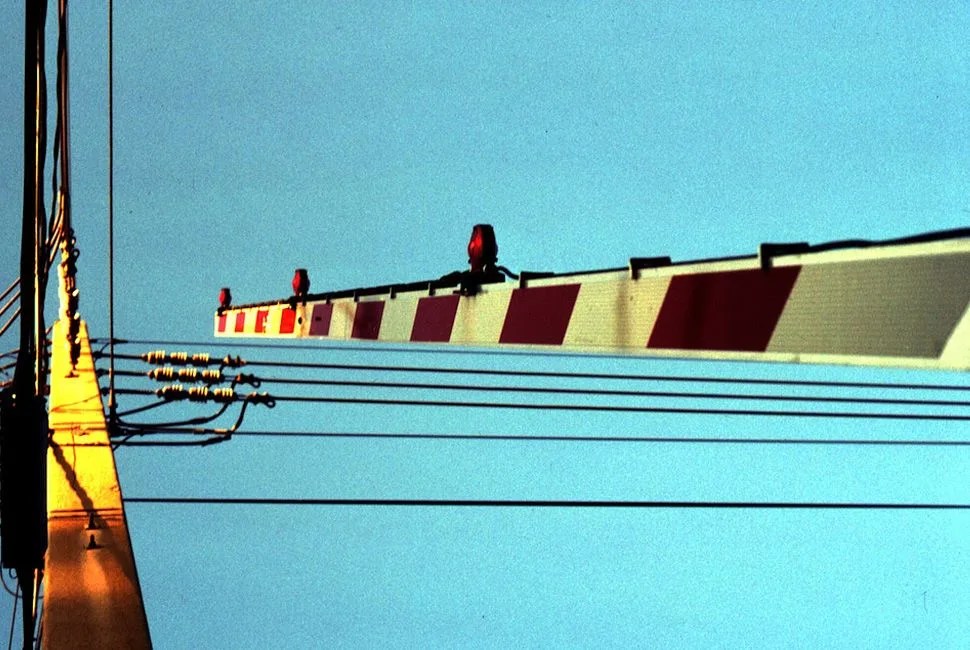

The professional sphere argued that Kodachrome gave photographs unrivaled depth, contrast and color saturation, all while retaining a refined elegance that seemed wholly natural to the subject. For the amateur photographer, the merits of the film stock were harder to put a finger on; it just made pictures look better. Paul Simon famously engrained the film’s near-mythic qualities into the mind of the general public when he released his hit song “Kodachrome”, in which he sings, “They give us those nice bright colors/ They give us the greens of summers/ Makes you think all the world’s a sunny day.”

The reality of 2009, however, was that Kodachrome sales had already for several decades been in steady decline. (Kodak had already discontinued 120, K25 and K200 films starting in the 1990s.) Digital photography was the new standard, and the cost and labor required to manufacture, process and develop Kodachrome wasn’t warranted by its current sales. In the summer of 2010, with the necessary chemicals needed to develop Kodachrome wholly exhausted, Dwayne’s Photo, a film processing lab in Parsons, Kansas, developed the last roll of Kodachrome, which, in a nod to the film’s back story, had been commissioned to photojournalist Steve McCurray on assignment for National Geographic.

Today, rolls of expired Kodachrome are still around, available to photographers on the secondhand market. They’re also affordable. The catch: Though expired film can still be shot, no lab can perform K-14 processing, Kodachrome’s developing process, without the necessary chemicals. Proficient labs will still accept rolls for cross-processing, meaning that the film will be developed into black and white images. These photos, at best, are a simple vestige of a long-gone film stock. They do not represent the spirit of Kodachrome; they do, however, stay true to the ethos of analog photography, encouraging experimentation, chance and discovery. This is the current state of Kodachrome.

Below is a compilation of photographs taken by both professional and amateur photographers using Kodachrome, obtained from either the Library of Congress or through Creative Commons Licenses. They represent the breadth of the film’s past glory, achieved over its 75 year lifespan.

Editor’s note: Click through a photos caption to learn more about the image.