Maybe you, like any red-blooded American man, still harbor some rock star dreams. Or maybe your friends have grown tired of your impassioned, point-by-point tirades about how Game of Thrones books are better than the TV show, and you’re thinking of confining those rants to a podcast format. Perhaps you’re trying to get some more audio/video content up and running at the website you work at (hear, hear!).

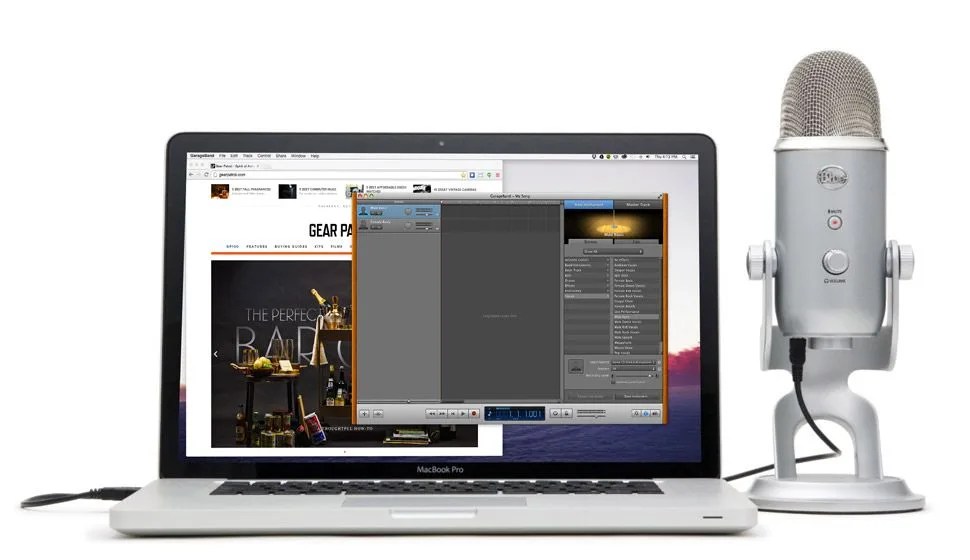

Home recording, for many reasons, is an enticing hobby — but a potentially expensive one. There’s no need to convert your basement into a recording studio if you just want to talk into a microphone or record some jams; between soundproofing ($3,000-$5,000), an analog microphone (at least a couple hundred for a high-end one), a mixing board (near $1,000 for a good one), amplification devices (again, at least a couple hundred), a home studio can easily exceed your average automotive down payment. It’s best to start small. To that end, a USB mic is a fine choice for beginners, despite the naysaying of aging audiophiles and recording technicians. (You know the type: bad ponytails, Zildjian tee shirts.) A USB microphone is a simple recording device that plugs right into any USB port 2.0 or higher — no intimidating EQ decks, no jumbles of cords. Sure, you should understand the difference between hypercardioid and omnidirectional polar patterns (it’s simpler than it sounds). But you don’t need to know everything a pro knows, nor do you need everything a pro has; a USB hub and the right USB microphone will go a long way.

How a Microphone Works

In the simplest terms possible, microphones pick up changes in air pressure — sound, in other words — and convert them into electrical signals, which feed into either a recording device or an amplifier. There are three common microphones on the consumer market that carry out this process.

In a typical dynamic microphone, a disc-shaped metal diaphragm catches vibrations in the air. This is the part of the microphone you holler into at karaoke; the diaphragm vibrates in such a way that replicates the air pressure variations caused by your rebel yell. The diaphragm is connected to a conductive wire, which is coiled around a magnet, creating an electromagnetic current. The wires uncoil towards the end of the magnet and run to the recorder or amplifier; what they pick up is the alterations in the electromagnetic current, which is caused by the vibrations that the coil receives from the diaphragm. The other two microphones covered in this guide — the most commonly produced mics on the market — are variations on this basic mechanism.

In a ribbon microphone, the diaphragm is a thin strip of corrugated conductive material (usually aluminum) rather than a disc. This diaphragm is highly sensitive to vibrations, making it highly susceptible to detailed recordings and potential damage in uncontrolled situations. (The mic was invented in the 1920s; it’s the iconic square-shaped mic seen in depictions of old radio broadcasts. The sensitivity of these microphones was, in part, what led to the development of “crooner”-style singing, as well as the typical muted sound you hear in 1920s recordings of brass instruments; you had to be careful not to blow out a mic back then.)

Like the traditional dynamic mic, single wires are attached to either end of the diaphragm; however, those wires do not coiled around a magnet, but run directly to the recorder or amplifier. Instead, two magnets stand on either side of the metal ribbon, generating a magnetic field; the ribbon acts as a conductor, producing electromagnetic currents with its vibrations, which are sent through the wires.

A condenser microphone is what most people want for home use. Whereas dynamic and ribbon microphones are powered by their magnets, condensers require a power source, referred to as “phantom power”. This is because the condenser mic uses a diaphragm and a stationary metal plate, each with a single wire attached, as opposed to a single diaphragm with two wires that produces a continuous circuit. The stationary plate stands behind the diaphragm, which functions as it always does, and the wires from the two metal pieces run parallel into your recorder or amplifier (usually the former with condensers); the catch is that the stationary plate is hooked up to your power source, creating a magnetic field in between it and the diaphragm. The variations in that field, caused by your voice, are what transmit through the wires and land in your computer.