You’ve spotted it on the train, on the street during fashion week, in the window of a very niche store and in a Japanese fashion magazine or two: a shoe with a moccasin-style toe and a little green tag. Chunky is certainly an apt descriptor, but clunky suits the very senior-looking shoe far better. The brand, Paraboot, has been operating in France since 1908.

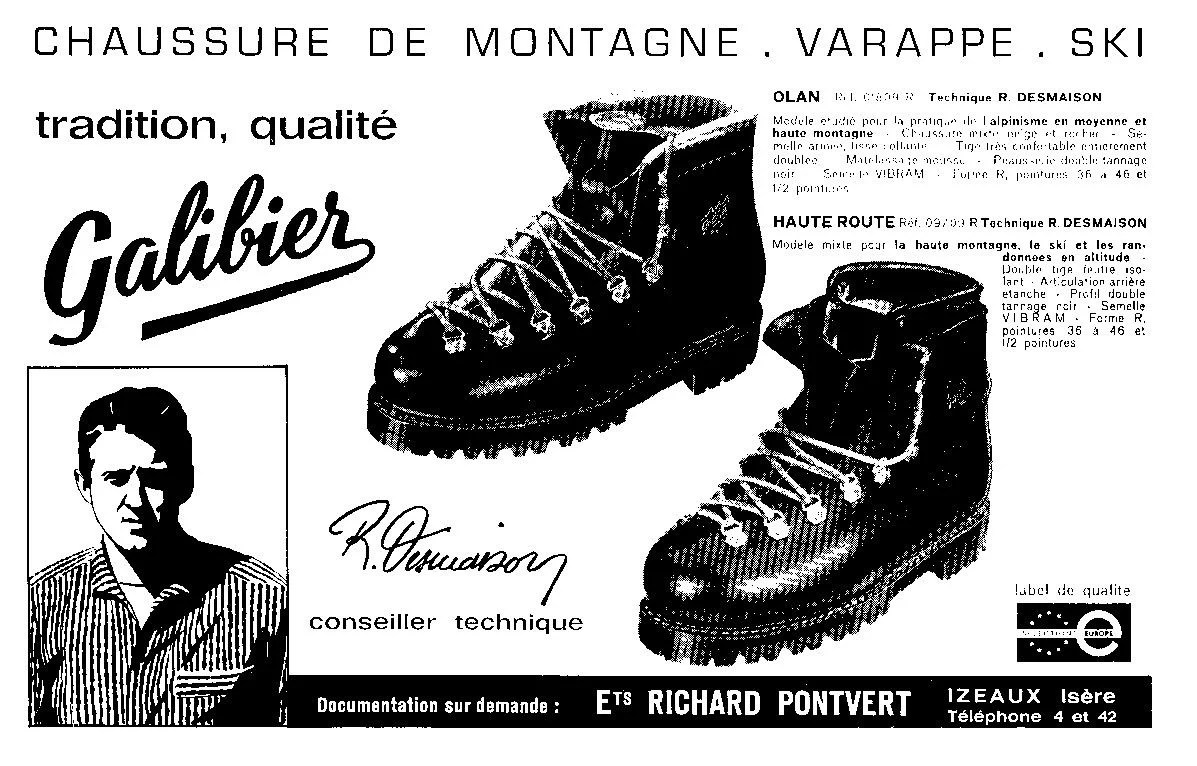

Before hiring his first employees, Rémy-Alexis Richard grew up in the small village of Izeaux at the foot of the French Alps during the late 1800s. He worked at factories that produced shoes for contractors in Paris. Richard eventually became a contractor himself and sold his designs for production in the very same factories. He would soon marry a wealthy woman named Juliette Pontvert and the two pursued the business together under the name Richard-Pontvert.

WWI would pull him away from his shoe business for a few years — he built and repaired shoes for the French army. After the war ended, he bought a factory back in the same town of Izeaux as a means to better control the manufacturing process.

In 1926, Richard traveled to the United States where he encountered vulcanized rubber boots. He brought the innovation back to his Alpine factories and combined this process with his method for applying notched soles to mountain boots, which at the time were affixed to wooden soles. Notched soles provided more traction on the terrain and, when applied to rubber, resulted in even greater grip. Today, the company still produces its soles in-house, a distinct feature of Paraboot’s business. In fact, when Richard registered the name Paraboot in 1927, he named it after the Brazilian port of Para, where the brand still gets its latex rubber for its soles.

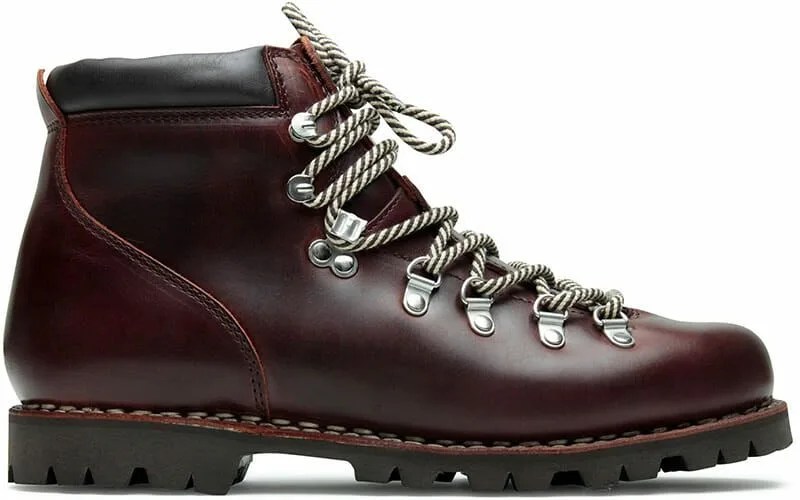

In 1945, as factories were closing or pivoting to cheaper production methods involving plastic, glue and lightweight materials, Paraboot decided to stay the course and continue making shoes using Norwegian and Goodyear welt construction. It was at this time Paraboot developed its iconic Michael shoe, a Tyrolean-style shoe originating from the Alpine region of Tyrol built for traversing the mountainous terrain. This hefty shoe is likely the style you’ve seen on the feet of industry insiders and tastemakers.

Courtesy

Courtesy