It’s said that at any given moment, half of the world’s population is wearing blue jeans. The estimation probably isn’t far off. The garment, originally known as a work pant, is now everywhere, and they suit everyone. “This one garment can be both universal and individual at the same time,” fashion historian Emma McClendon says in PBS’s documentary, Riveted: The History of Jeans. “There’s nothing like that in the history of clothing.”

But the history of blue jeans has been edited to better suit its biggest producers, Levi’s and Wrangler, a documentary by PBS, reveals. While dry good supplier Levi Strauss and tailor Jacob Davis are credited with mainstreaming denim pants with reinforced stress points and pockets, there are people both before and after them that deserve credit for creating jeans as we know them.

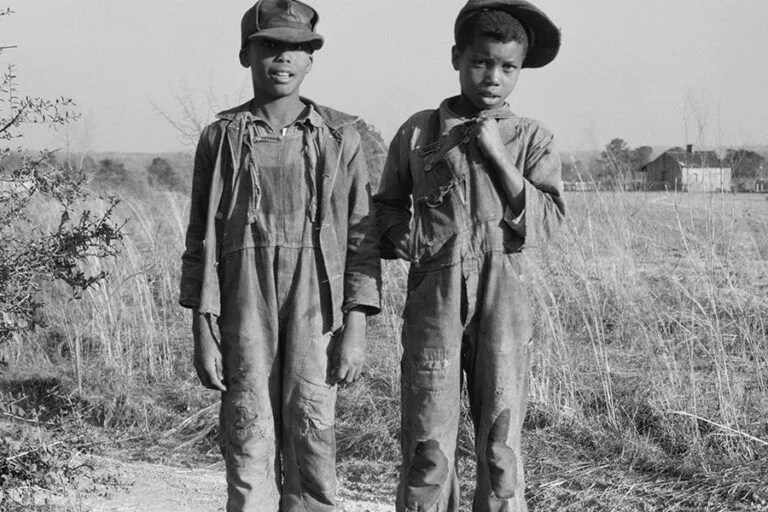

Sure, cowboys and those working in America’s Wild West served as incredible advertisers for these newly American bottoms, but “denim was changing and so was America,” McClendon continues. “That image of someone clad in denim at the turn of the 20th century is inevitably, you know, romanticized. And the reality is that people of all different ages, races, and genders were wearing denim during this time.”

PBS

PBSNot only was imagery of those who wore jeans whitewashed, but the history of production was, too: from who taught American hows to cultivate and use indigo to who exactly even invented coarse, blue cotton pants in the first place. Indigo can be traced back to Dungri, India, (carried on colloquially through dungarees), where workers as far back as the 17th century wore tough blue pants dyed with indigo; Genoans (where the word jeans derives from) in Italy made waxed work pants; and in Nimes, France, indigo-dyed cloth was called “de Nimes” (the root of the word denim).

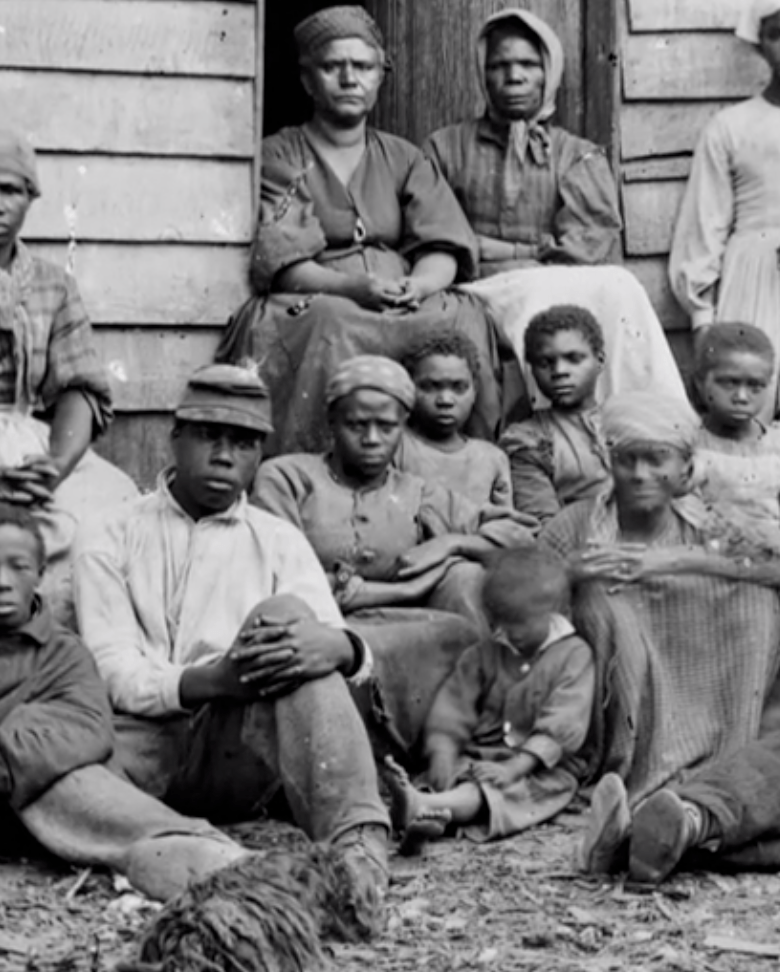

The knowledge to grow indigo came from enslaved people.

In Africa, indigo was used as well, and when many West Africans were taken captive and relocated against their will to America, they brought the trade with them, passing the knowledge to white, slave-owning families across the south. And, like this country has with many other popular products, the knowledge of these captive peoples’ contributions was written over. The US’ history curriculum celebrates the daughter of a colonial governor, Eliza Lucas, for cultivating indigo and kickstarting its production as a cash crop in South Carolina.