In an 800-square-foot studio in Brooklyn, just off of Driggs Ave, before it runs past a massive Russian Cathedral and into McCarren Park, Daniel Lewis, founder of Brooklyn Tailors, designs suits for what GQ called the “creative class”. When New York Magazine covered him, they called his clientele “men who find J.Crew a bit too fratty and APC a smidge too French.” But Lewis puts it more broadly: he makes suits for men “with nowhere else to go.”

Daniel — Danny to his wife Brenna, who manages the business — looks much like his clothing. He’s slight and lean, maybe a little shorter than average, but hard to miss. When clients come into his studio for the first time, he meets them at a glass table, his legs crossed and his hands held with a delicate tenseness, listening intently to how they want their suit designed. He listens with the same purpose he puts into his clothing. No movement wasted. Nothing to excess. His jaw is squared and his hair is styled into jets of black, sprayed causally back and matching the dark grays of his shirt and the cut of his suit and pants. He looks good.

Before Daniel started Brooklyn Tailors, he was a menswear designer. He was also his own customer. Someone who wanted to find the perfect suit, with the right style, a slim cut, made of good quality and at an affordable price, but he had nowhere to go. So he made one himself. A photographer and musician, Daniel expanded his creative output to suits, shadowing tailors and then, almost a decade ago, started taking customers out of his small Brooklyn apartment. Word of mouth spread, and one day in 2011 the duo realized they had outgrown their apartment office.

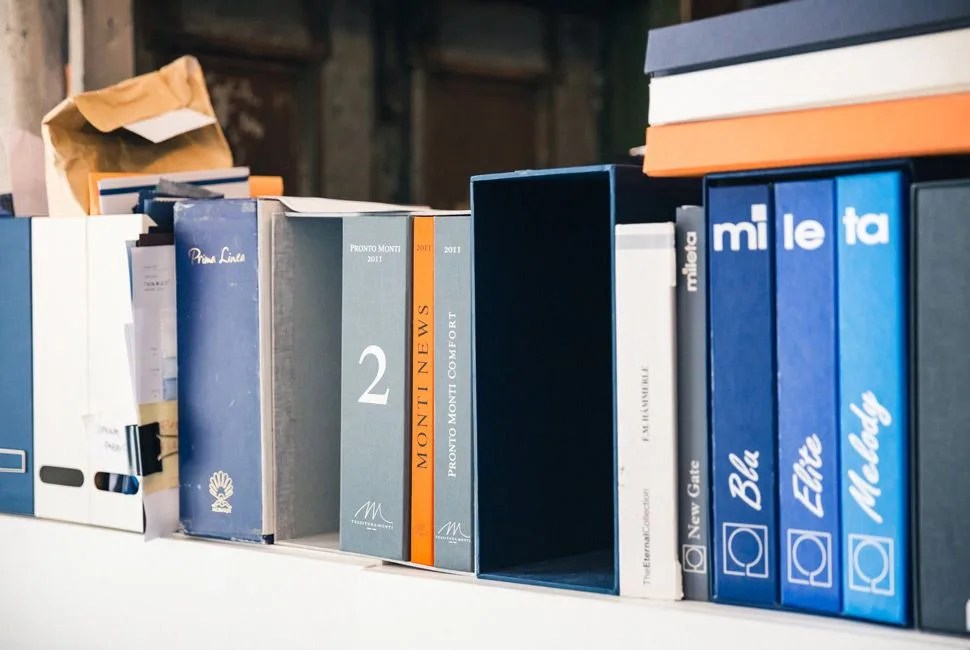

They renovated their current 300-square-foot store in Williamsburg (currently just a little ways away from the larger studio) themselves with trips to Home Depot. Both still held down their full-time jobs. “We would get on the subway, go home, and then take fittings from 7 to 10 every night, eat dinner, go to bed, wake up and do it all over again,” said Brenna, dressed in a black dress and matching black shoes. “We worked seven days a week for four years straight.” Only a few months later, in August of 2011, Daniel quit his job to focus full time on the business, while Brenna soon followed, quitting in May, 2012. The following year, in 2013, they expanded once more into the Brooklyn studio space where I met them, which itself is a stopgap space until they open a larger store and studio in 2016. Collaborations with Gap and GQ‘s 2014 Best New Menswear Designer award fueled an already rising business. Boxes with orders from Barney’s, Journal Standard and Penelope’s are already crowding the expanded space.

Lewis’s designs aren’t flashy; they are recognizable for their shapes. The height of the lapel, the proportions of the pocket, the way the shoulder structure just sort off rolls off into the arm, instead of squaring.

“I was really into Dylan, the Stones, the Beatles. And more contemporary, it was Nick Cave and Ryan Adams, The Strokes, Tom Waits, and all in different ways, all those guys wear tailored clothing really well,” said Daniel, explaining what inspired his style, which ran counter to the broad shapes of Brooks Brothers back when a slim fit wasn’t as popular as it is today. He says there was a time when office jobs required a suit and a tie, so the suit was a uniform. Now, with techies in hoodies and coffee shops full of freelancers who never enter an office setting, the suit is back as a choice, not an obligation.