“In 2011, we didn’t own a sewing machine,” Todd Shelton admits. “And that was a problem.” His brand, Todd Shelton, sold clothing. The operation was 10 years old.

Now 14 years old, Todd Shelton’s company owns 55 sewing machines, a fusing machine and a handful of other speciality machines that help make their line of T-shirts, button-downs and jeans. It’s a clothing company that makes their own clothes in their own factory with their own employees.

If Todd Shelton were a brewery, all this would be obvious. We don’t drink craft beer that’s made somewhere in a giant factory and then marketed and distributed by a brewery. Beer makers make their own beer, at their own breweries, and it’s a simple, mostly vertically integrated company concept. But craft clothing is not craft beer. Most all startup clothing companies make a design, contract with a factory and then get their goods made domestically or abroad. Shelton did that, too, for 10 years. But to him it never made sense.

One Sewer, One Garment

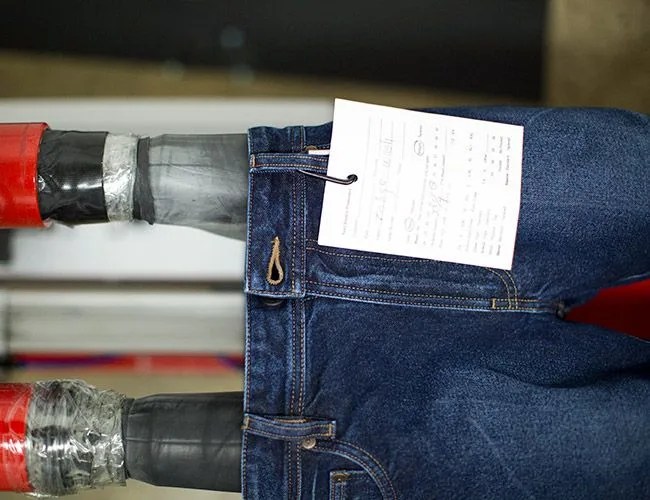

Ana De Ortiz and Isabella Fernandez make jeans; Carmen Romero and Lorena Ramos make shirts — from start to finish. Shelton has a reason for this. He believes in the dignity of the maker (“one operator on one machine isn’t a cool job”), and he’s fastidious about fit (“the fit is the value in this product”). So, for each piece of apparel that Todd Shelton makes, there’s one person who oversees its production entirely.

This also, naturally, slows things down — there’s a reason that the factory assembly line caught on. But for what Shelton loses in speed, he gains in quality and employee empowerment. Shelton points out things like how clean the stitching is in a garment, and how the belt loops don’t have unfinished ends, which can lead to fraying. He also believes that the pride that comes in creating an individual piece of clothing, as one’s own complete creation, is worthwhile for company happiness. It’s a small shift of creation over repetition.