7 photos

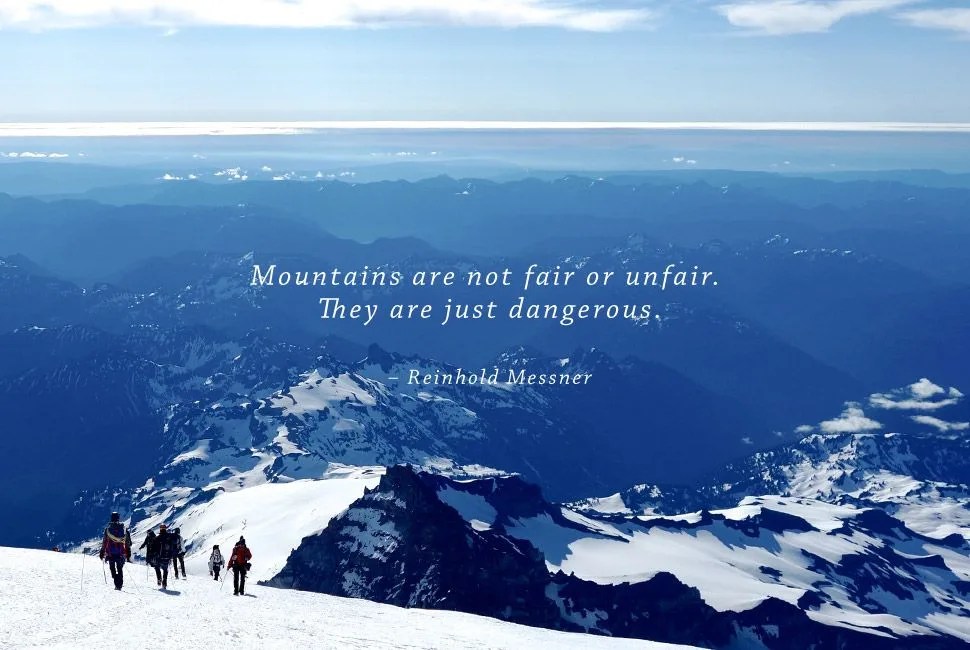

Unlike heat or cold or wind or fatigue, which had all made themselves unpleasantly known in raw physical ways, gravity was more insidious, creeping inside my bones, my brain and deep in my belly. Though I couldn’t see the 45-degree drop over my left shoulder in the predawn blackness, it was as real as a person whispering in my ear as I picked my way through the mixed rock and ice of the Disappointment Cleaver. I could hear the forced exhales of my rope mates, pressure breathing above me, crampons scraping on bare rock with a metallic clink and the wind whistling past my hood. The sounds were sharp, somehow accented by my heightened senses and perhaps by the thinner air, yet above it all was my own voice inside my head saying “don’t slip, don’t fall”. I craned my neck up until my helmet knocked against the top of my pack. A string of headlamps stretched far above me like Christmas lights. We had a very long way to go and it was impossibly steep. It was dizzying. I looked down, deciding to focus on the quarter-inch rope and each step in front of me.

MORE FROM LIMITS: Introducing, The Road to La Ruta | Photo Essay, Climbing Ancient Art Tower | Single Track Mind: The Best American Mountain Bike Trails

Mount Rainier rises 14,410 feet above the landscape two hours to the southeast of Seattle. It towers above its surroundings, dwarfing the smaller peaks of the nearby Tatoosh Range and creating its own weather systems. It is the largest and most heavily glaciated peak in the lower 48 states. From the city on clear days, it is a beacon, almost a benevolent presence. Yet Rainier is considered one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the Western Hemisphere. Should it ever erupt again, the resulting mudslides and ash would threaten not only Seattle but much of Washington state and beyond.

For climbers, Rainier presents a tantalizing challenge given its accessibility to a major urban center and the established routes that zigzag up its flanks. Its topography and numerous glaciers and crevasses make it an excellent training ground for bigger climbs in the Alps and Himalayas. Only about half those who attempt to summit it succeed each year, the other half turned away by weather, unstable conditions or fatigue. It was also the scene of one of the worst mountaineering accidents in North American climbing history when an ice fall killed 11 climbers in 1981.

After years spent diving the warm waters of the Caribbean on vacations, I was feeling the Alpine itch again. Creeping along into my forties, I felt I was growing too soft and the mountains were calling. A decade earlier, I had bagged a couple of 14ers in Colorado, but never attempted a true technical climb on a big glaciated peak. So I signed up for a summit climb with Rainier Mountaineering Inc., out of Ashford, Washington. I had read that climbing Rainier was doable for anyone with minimal mountain experience and good fitness. In retrospect, this seemed like an understatement.

To my left, the peaks of the surrounding mountains were coming alive in false warmth of the sunrise; to my right, the forbidding blue crevasse.