For a long time options for buying a bike were limited to what was at the local shop, which was a roll of the dice in terms of selection and service. In many ways, the manufacturer-distributor business model is antiquated and direct-to-consumer sales are the way forward. With e-commerce consumers have limitless information available at a mouse click. What does this mean for the bike buyer? You have options.

Purchasing a bike online used to be nigh impossible, but sites like Competitive Cyclist and Wrench Science are making it easy and worthwhile to get a high-quality ride off the web. However, if you’re in the market for a performance bike, it’s still expensive. Luckily e-commerce has also allowed for inclined customers to buy individual components. The wonders of a global marketplace also mean that in some instances you can buy components online from reputable European shops for less than your local bike shop can get them wholesale.

This availability opens the door for a bike purchasing option that didn’t really exist until the last 10 years: riders can now build their bike piecemeal, purchasing each individual component either new from online retailers or used from auction sites and classifieds. The result is a bike that can be built entirely outside of the bike shop system and that can be tailor-made to fit your specific wants and needs. That’s a recipe for high quality at low cost — so long as you know what you’re looking for.

With the experience of working in a bike shop under my belt and a good idea of what type of bike I wanted, I decided to try the “internet bike build” myself. With a budget of $2,000 I set out to best some of the similarly priced complete bikes for sale at the local shop.

Step 1: The Frame

The first order of business was to pick out a frame. The choice was easier than you’d think given the cost restrictions. I’ve ridden carbon fiber frames for the past six years, spending more money than I’d like on composite frames that purportedly are both lighter and more comfortable than aluminum. However, the difference between high-end aluminum or steel and mid-grade carbon (which are often around the same price) is not nearly as vast as some marketing departments would like you to believe. With limited funds, a new high-end carbon fiber frame was out of reach, and used carbon can be rather dodgy: the material can fail suddenly and dramatically, so unless you’re sure of the frame’s history it’s best to look elsewhere. The final requirement was that the frame had to have been made in roughly the last decade so there wouldn’t be any compatibility issues with modern components. That left me looking at flagship aluminum frames from 2002-2005 (the last years aluminum was used in the pro ranks). As soon as I knew it had to be aluminum, I knew it had to be a Merckx Team SC.

It wasn’t too much trouble to set up a bike stand at Gear Patrol HQ, put on some Creedence Clearwater Revival, open up a refreshing carbonated beverage and get to work.

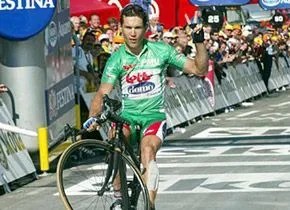

The Team SC was the coolest pro bike from the era when I really fell in love with cycling. While Lance Armstrong was busy capturing wins at the Tour de France on a Trek, guys like Johan Museeuw, Richard Virenque and Peter Van Petegem were capturing my heart with gutsy attacks and huge wins. All of these guys rode for the Lotto Farm Frites (yeah, thats a French fry company) team that later became Lotto Domo. They rode the Team SC to wins at the hellish Paris-Roubaix and on top of the insane Mont Ventoux. Lance was cool, but the Lotto Domo guys were the ones you wanted to root for; these guys had panache. Couple the Lotto mystique with the fact that the Team SC was actually a pretty excellent bike and I was obsessed. I’ve dreamed of owning a Team SC for 10 years, so I figured it was fate when I found a mint Team Lotto Domo frame for $450 on eBay (never mind if it was a little too big).