Road bike shifting has come a long way in the roughly 75 years it’s been around. The number of gears has ballooned from 2 to 11, shifters have moved from the frame to the brake levers and traditional cable actuation is poised to give way to electronic shifting. There’s little doubt that the revolutionary new tech, which replaces traditional steel cables with small electric servos, will eventually become commonplace. Two decades ago that couldn’t have seemed further from the truth.

MORE GP CYCLING: The Best Road Bikes for Any Rider | Interview with Cannondale’s Henning Schroeder | The Best American Mountain Bike Trails

Early Attempts at Electronic Shifting

In the 1990s, when most people were happy wearing bucket hats or slapping bracelets, Mavic, the famed French wheel maker, was busy trying to get electronic rear shifting to work. The company started in 1992 with the Zap, a product with a suitably ’90s name that was an interesting proof of concept but broke quickly and ran out of battery even quicker. Undeterred by failure, the hommes at Mavic tried to raise the bar again with Mektronic in 1999. The new system used radio frequencies to wirelessly shift the electronic rear derailleur; the idea sounded excellent on paper but didn’t stack up to real-world use. Since the derailleur had to house a battery, radio and the servo, it was impractically heavy.

More importantly, it didn’t work. Early adopters figured this out as soon as they rode too close to power lines or their local radio station and their bike started shifting with a mind of its own. Mektronic proved conclusively that Mavic, bless their hearts, could not make a worthwhile electronic group. It also proved that electric drivetrains are really hard to get right. So hard that one of the biggest names in cycling had effectively created a list of what not to do. Future electronic groups would have to be reliable, durable and — for god’s sake — not wireless.

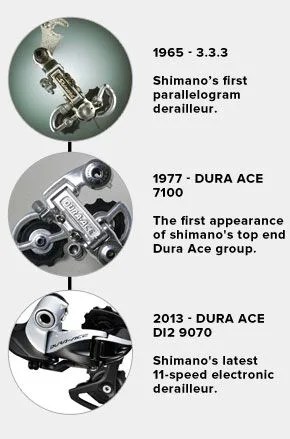

Shimano: An Evolution