A version of this article originally appeared in the Craftsmanship issue of Gear Patrol Magazine with the headline “Death Metal.” Subscribe today

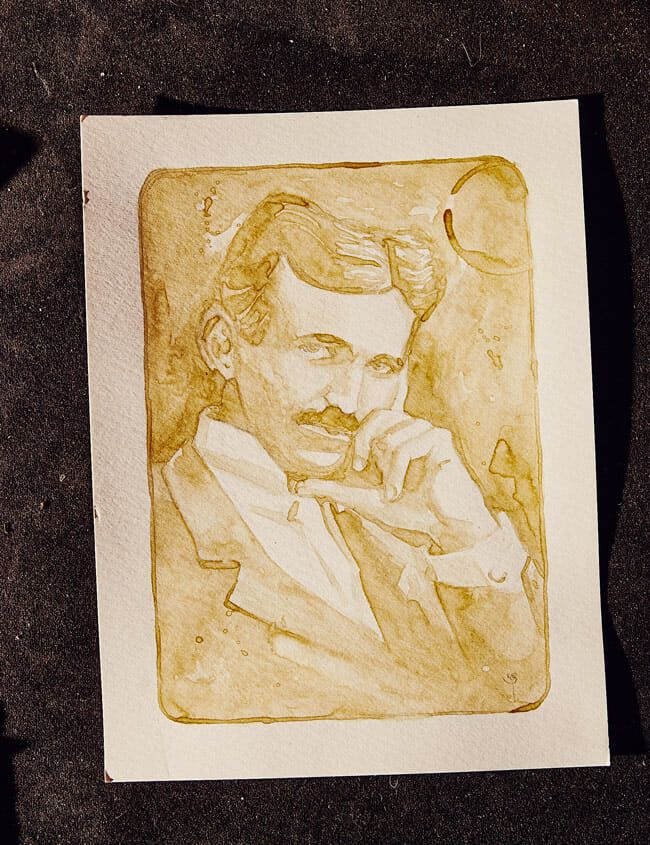

Joey Arbour is appalled. Or maybe he’s feigning it, I can’t really tell. I’ve known him for only eight hours and we’ve been drinking beer for the last five. He’s staring at me, blue eyes wide, brow furrowed. For the first time all day, there’s an uninterrupted silence. It had seemed like a reasonable enough question to ask: If you’re going to have an artist create a portrait using only beer as the paint, why choose Nicola Tesla as the subject?

Joey lowers his can of Pabst Blue Ribbon, nestled in a coozie reading “A Fist Full of Fuck Yeah,” to the arm of the second-dirtiest chair in all creation. The dirtiest is to his immediate right. Finally, he blurts an answer:

“Because he’s fucking awesome!”

About this there’s no disagreement from any of the five of Joey’s employees sitting around an enormous table stacked high with empty PBR cans and rapidly filling ashtrays. In fact, the group considers Joey’s opinion of the Serbian-American inventor to be manifestly true, along with the contention that Tesla’s rival, Thomas Edison, was kind of a dick.

Other things that the crew believe to be true: if you’re going to drink and smoke, your goal should be to do so until you sound like Tom Waits; physicists suck, David Bowie was great, Hunter Thompson was the best; and that, at more than 1,000 pages, Carl Sandburg’s only novel, Remembrance Rock, is a little tedious.