3 photos

There are two kinds of helmets: those with MIPS, and those without. You can spot a MIPS helmet pretty easily — just look for the little yellow logo near the helmet’s rim, or the strange yellow interior of the helmet’s shell. What is MIPS, and why is it so important? The story of MIPS (Multi-Directional Impact Protection System) began in 1995 when Hans Von Holst, a brilliant neuroscientist, teamed up with Peter Halldin, a relentlessly inquisitive engineer, and decided to change the world. Their goal: to drastically reduce, and eventually eliminate completely, brain injuries in all sports.

Twenty-two years after its story began, MIPS is well on the way to achieving its ultimate goal. Nearly every major bike and motorcycle helmet manufacturer offers at least one MIPS-integrated helmet; many offer several. And the science becomes clearer every day: helmets with MIPS reduce brain injuries more effectively than those without.

“The reason to choose a helmet with MIPS is to have additional support and protection during certain impacts,” says Johan Thiel, the CEO of MIPS. “[MIPS] is very cheap insurance for additional protection. And the most dangerous injury when you’re wearing a helmet is a brain injury.”

How does MIPS work, exactly? Thanks to some clever engineering, MIPS essentially mimics the brain’s cerebrospinal fluid, which is our bodies’ second line of defense against brain injury. (Our skull is the first.) When hit with oblique impact, two layers — the helmet’s foam outer shell and MIPS’ patented inner shell, connected to one another by omnidirectional elastic bands — rotate independent of each other, thereby absorbing and diffusing the energy of the impact much better than a standard helmet. (Still confused? Go here.)

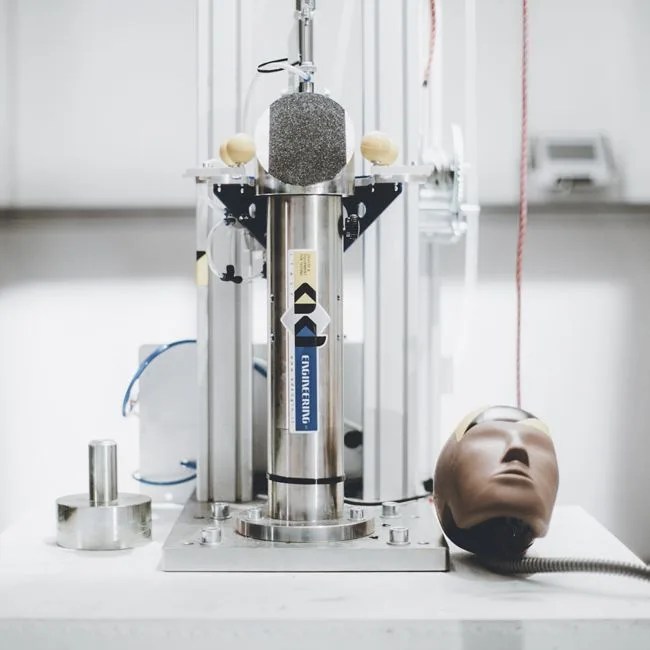

MIPS isn’t a consumer product. You can’t buy an individual MIPS shell and install it in your own helmet. Rather, MIPS is an ingredient in consumer products. It can take months, sometimes years, to properly integrate MIPS into a helmet. At its headquarters in Sweden, MIPS tests product concepts in a gleaming, echoey laboratory, where helmets are repeatedly smashed with battering rams and crash test dummy heads are launched into the ground; the data extracted from these tests is then used to produce new, safer helmets. In an effort to make helmets safer across categories and brands, MIPS even publishes many of its research papers on brain injuries and oblique impacts to the skull online.