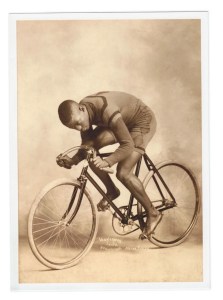

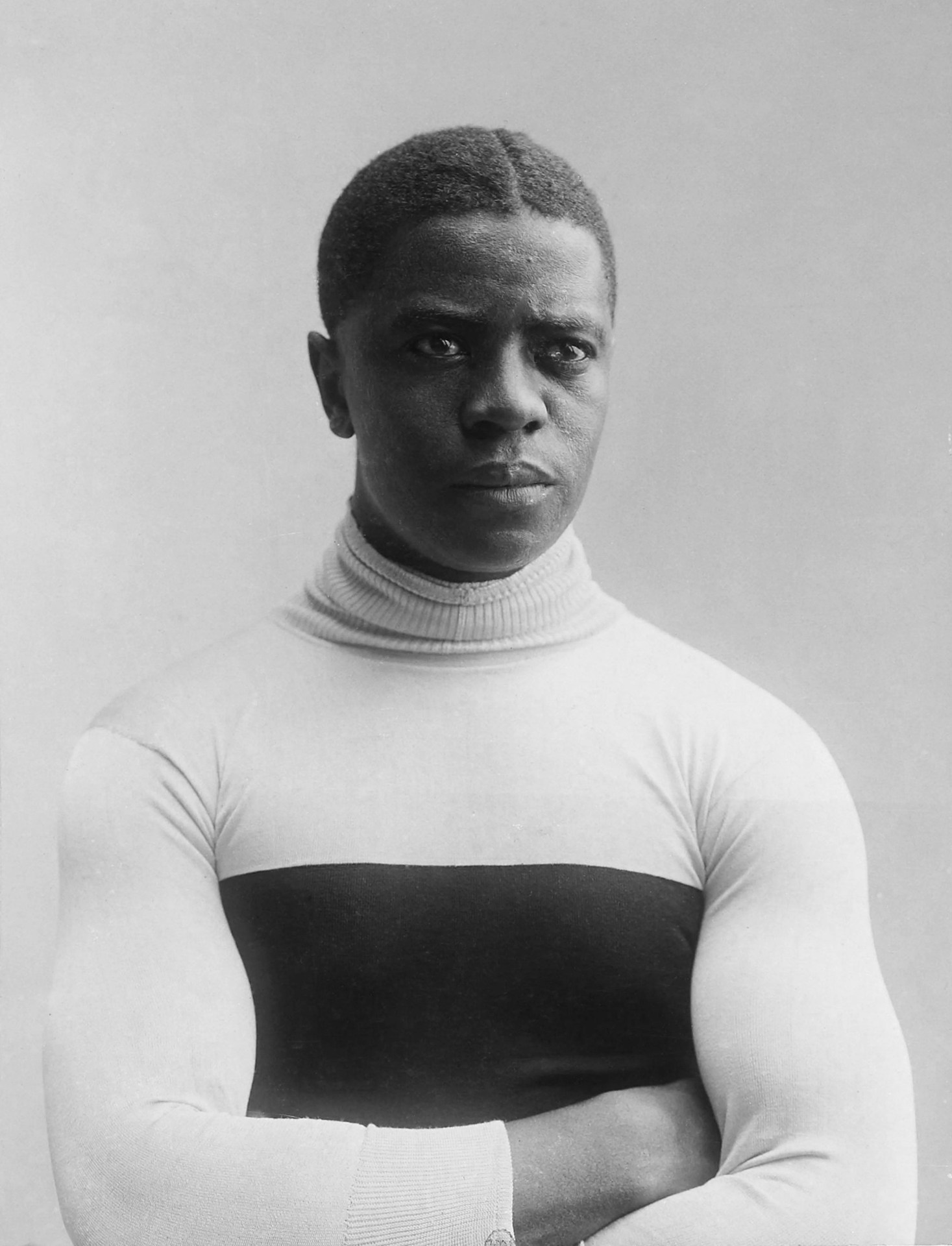

“In a word I was a pioneer, and therefore had to blaze my own trail.”

So said Marshall Walter “Major” Taylor, cycling’s first African-American world champion, whose incredible story still isn’t as well known as it should be.

Born just 13 years after the end of the Civil War, Taylor got his nickname as a youth for wearing a military uniform while performing bike tricks outside a local shop in his hometown of Indianapolis.

A few years later he was winning his first pro race at Madison Square Garden, then traveling the globe, beating the best that Europe, Australia and New Zealand could throw at him and setting seven world records, one of which lasted 28 years.

Rising against adversity

His growing fame and fortune made him one of the sport’s early superstars — and one of the first Black sports celebrities of any kind.

This despite not competing on Sundays due to his devout Baptist beliefs — and in the face of ugly, brutal racism.