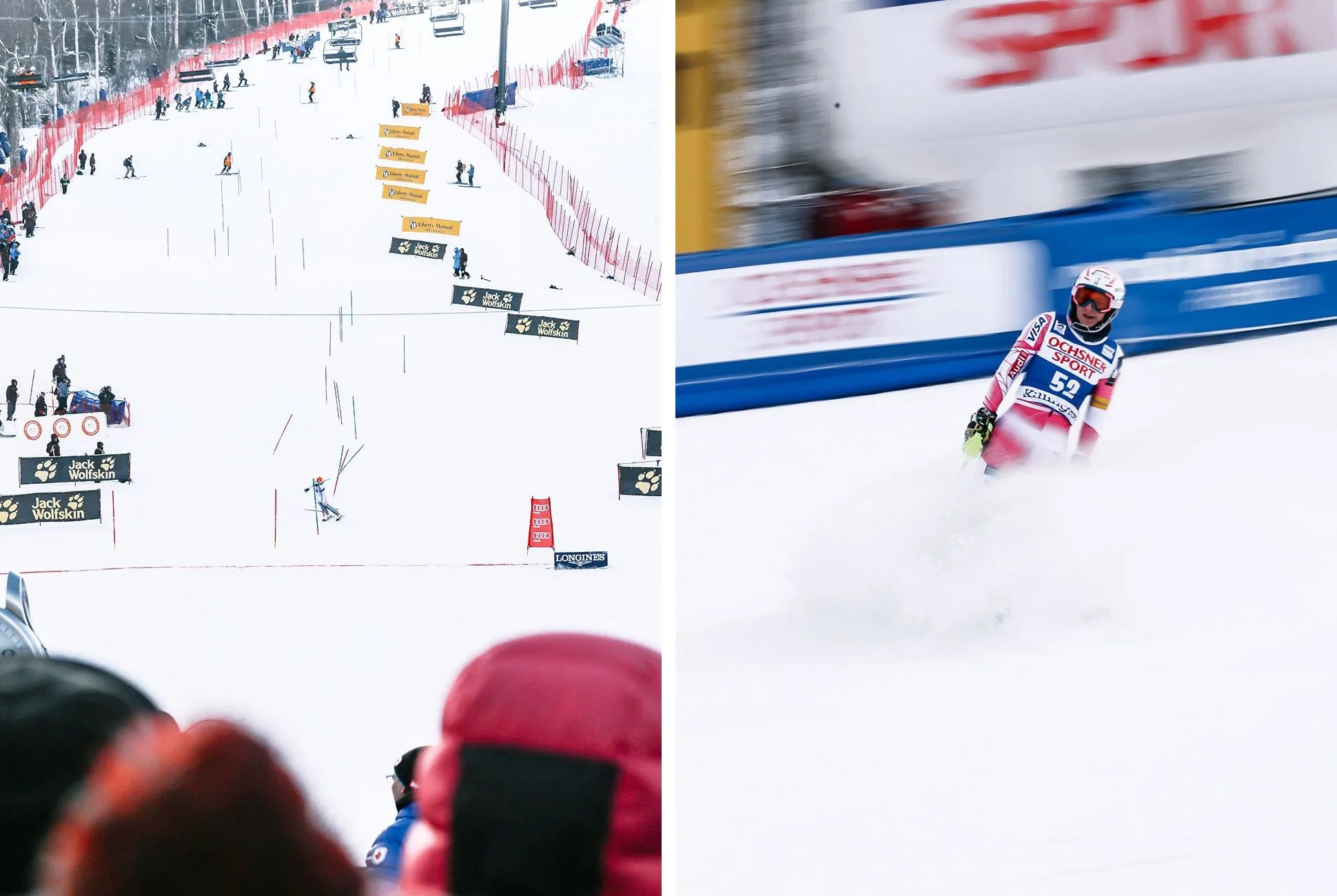

The first Saturday after Thanksgiving, thick November fog morphed and undulated over Killington Peak, the second tallest mountain in the state of Vermont and the largest ski resort on the East Coast. Even at 4,235 feet, winter was still young; only a few trails at Killington were open to skiing and snowboarding. And yet down below, the parking lots were overflowing. Dedicated fans waited in an hour-long shuttle line at nearby Pico Mountain or hiked the last few miles of road shoulder, thumbs extended, to Killington’s K1 Base Area. The crowd gathered at the bottom of the Superstar trail, in view of the final pitch of the first FIS World Cup race course to come to the Eastern United States in 25 years. When a neon figure split the fog and smashed through the first visible gate, cheers and cowbells echoed off the mountain.

The FIS — the translated French acronym stands for “International Ski Federation” — World Cup is the Grand Slam of alpine ski racing. It was dreamed up in 1966 by alpine ski team directors Bob Beattie of the United States and Honore Bonnet of France. In every year since then, athletes from over a dozen countries have competed each winter in events that carry as much prestige as the Winter Olympics. The race schedule is demanding, with races held in a different country every week vying for the best times in slalom, giant slalom, super G, and downhill. There are big bucks at stake for the fastest racers; last year, Lindsey Vonn earned an estimated $434,870 in prize money. For a resort, hosting a race is a hefty investment but comes with its own merits in the form of global name recognition.

The recent women’s races at Killington broke a historic drought. It was the first World Cup for the resort, ever. It was also the first time in 25 years any World Cup event has been held at an East Coast venue — the last races were hosted by Waterville Valley in New Hampshire. It was the second time they have come to Vermont; the last time being the GS and slalom races held at Stratton in 1978, the same year that Fleetwood Mac released the album Rumours and the video game Space Invaders was developed in Japan. After 1991, US races went west to resorts like Park City, Utah and Vail, Colorado, and stayed there. Since 2003, every World Cup event in the United States has been held at Aspen or Beaver Creek, both in Colorado.

The last time the World Cup came to Vermont, in 1978, Fleetwood Mac had just released the album Rumours and the video game Space Invaders was being developed in Japan.

The West hasn’t always dominated the American ski racing scene. The first-ever US World Cup races were held at tiny Franconia, New Hampshire. After that, Waterville Valley, New Hampshire held a total of 11 World Cup events between 1969 and 1991, making it the venue with the fifth most races to its name in the country (behind the four aforementioned western resorts). Add races at resorts in New York and Maine and it becomes even clearer that the first 25 years of the World Cup were markedly more bicoastal than the last.

The women’s Thanksgiving races are typically held at Aspen in what FIS calls a “classic,” meaning a race that is held at the same venue every year. This year Aspen decided to host the finals and, because no resort can host more than one event in a season, a gap opened, allowing Killington to step in and place a bid. Becoming a first-time host is not easy. The FIS performs an initial evaluation of the course and the resort’s facilities, then lays down a strict set of requirements and deadlines for preparation. Bidding wars can also develop between resorts seeking the right to host, but thanks to some help from the US Ski Team, Killington was the only resort gaming for the spot this year. The opportunity to host the races was a “tremendous honor and opportunity for Killington and the surrounding community,” said Mike Solimano, the resort’s president and general manager. Their successful execution “had the entire town gushing with pride,” he said.

7 photos