“After swimming with a school-bus-sized fish with teeth, I’m not that impressed by celebrities anymore,” says renowned photographer Michael Muller. This may seem an odd statement from a man who first made his name shooting portraits of some of Hollywood’s biggest names. If you’ve seen the movie posters for any of the X-Men or Iron Man movies, you know Muller’s work. But when you see his other photographs, you begin to understand.

Over the past decade, the California native has dedicated much of his energy and considerable talent to photographing sharks. What started out of a fascination born from a childhood fear has turned into a passion for documenting and raising awareness for the plight of these endangered creatures. To achieve his powerful and unique style, Muller had to innovate with equipment, spend thousands of dollars on expeditions, and take some considerable risks to get up close to some of the most dangerous animals on the planet.

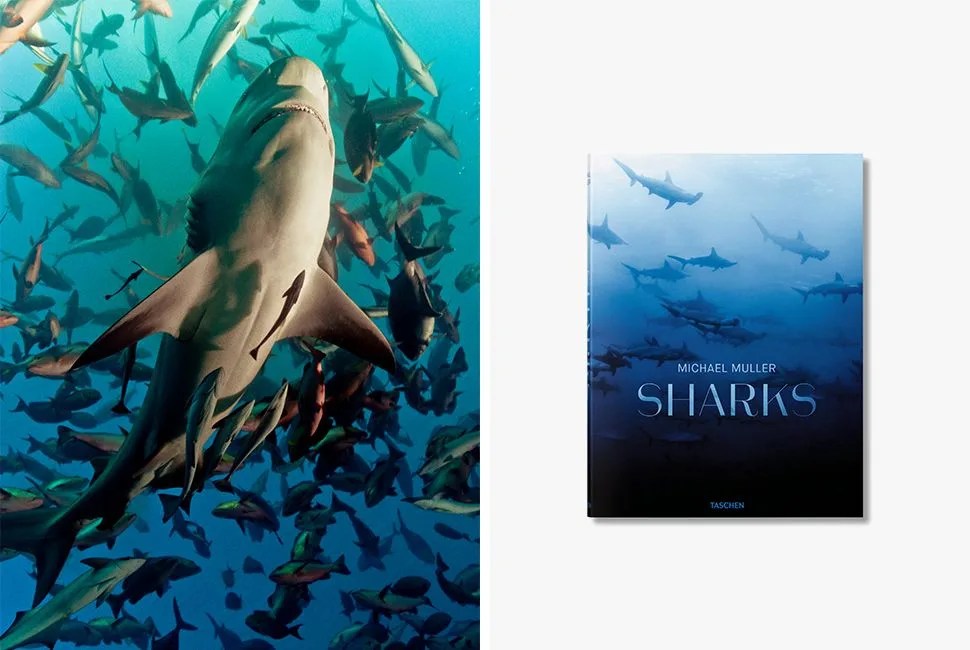

After a decade of shooting sharks of all kinds from the Galápagos Islands to South Africa to the Pacific coast of Mexico, Muller has pulled together his best work in a new book of photography simply titled Sharks, published by the German art book publisher Taschen. In it, this Hollywood photographer does what he knows best: treating these toothy subjects as celebrities, lighting up their best sides to show the world their beauty and power. We sat down with him during the launch of IWC’s limited-edition “Sharks” Aquatimer dive watch in Muller’s honor — both a fitting and an incongruous place to talk to a photographer who is as at home in Hollywood as he is in a shark cage.

4 photos

Q: How different is preparing for a movie shoot from diving with great whites? Are there similarities outside of making sure you’ve got a memory card in the camera and batteries charged?

A: When I’m dealing with a human, I can communicate. I can say, “Hey, turn here. Do this. Jump.” I can direct. With animals I don’t have that ability to direct, but I can direct them by where I put the lights, where we feed them. It’s more of a documentary process… and there’s no guarantee that sharks are going to be there. I’ve flown all the way to Africa and gotten skunked for a week with a film crew and my assistants. But I’ve gotten something from every trip.

Q: Your underwater photos are known for their dramatic lighting, from a system you developed.

A: I was in the car one day and thought, “I want to bring a great white into the studio, and edge light it and key light it.” I can’t bring the shark to the studio, so I’ve got to bring the studio to the shark. I started looking online, and these lights didn’t exist. You either have 400-watt strobes that every scuba diver uses, or big movie lights where you need a generator the size of a building.

I almost gave up and then I met this guy who makes housings for cameras and we brought in an engineer from the Jet Propulsion Lab, NASA, and developed the light, which I got literally the day before I left for the Galápagos to shoot an IWC campaign. It arrived at the house, I jumped in the pool, fired it and it worked. Off we went. Now I have a full studio going on: overhead, seven lights underwater all over the place, and they’re running from cables to batteries. Each light is 1,200 watts.