6 photos

You’ve seen the commercials by Gatorade, Nike and every other sports brand: An incredibly fit professional athlete connected to a bulky, high-tech breathing apparatus runs on a treadmill as multicolored sweat drops off his face. If you’re an “athlete,” like me, you’ve thought about what those tests could potentially tell you — and what those results could mean for your game.

The truth is, by and large they’re not meant for us. Athlete testing is designed to test athletes. Like, professional athletes. Not a beer-league-soccer, weekend-runner, semi-regular-cyclist, pretend athlete like me. As such, those facilities are mostly confined to medical labs at leading universities across the country as well as select few pro athlete training centers.

That leaves the average consumer few options, one of which is the NY Sports Science Lab on Staten Island. The brand-new facility — which is a part of the NY Chiropractic & Physical Therapy offices run by Dr. John Piazza and his wife, Susan Piazza — is one of two operations in the country making some of the best athlete-testing equipment in the world available to consumers.

As you go through each of the tests, you can’t help but feel like Roger Federer, or Odell Beckham Jr., or Meb Keflezighi. That is until you see the results, and realize that you’re only mortal.

The facility is small, but its personalities are big. Dr. Piazza, who’s the tall, suave type you’d expect to have a passion for classic muscle cars (which he does), owns the entire facility along with his wife Susan, who is a master in tae kwon do.

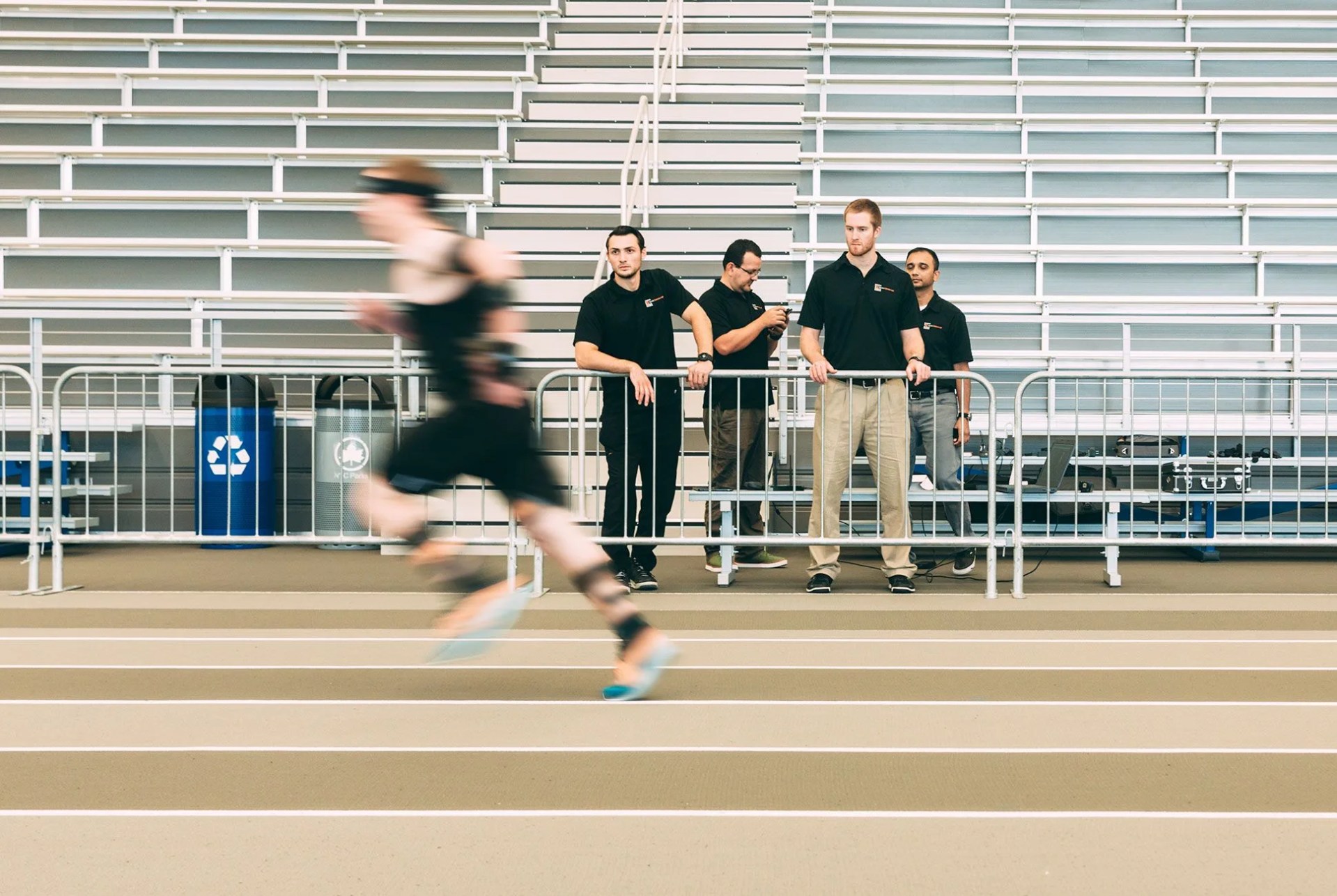

But they are only the tip of the iceberg. The team includes sports physiotherapists like Rushi Shahiwala, certified biomechanics specialists like Juan Delgado and Michael Greene, and Matthew Reicher, an athletic trainer who has spent time with a number of professional sports teams, including the Brooklyn Nets and the New York Red Bulls. As a group, NYSSL has tested Olympians that competed in the Rio games like silver-medal boxer Shakur Stevenson and bronze-medal fencer Dagmara Wozniak.