11 photos

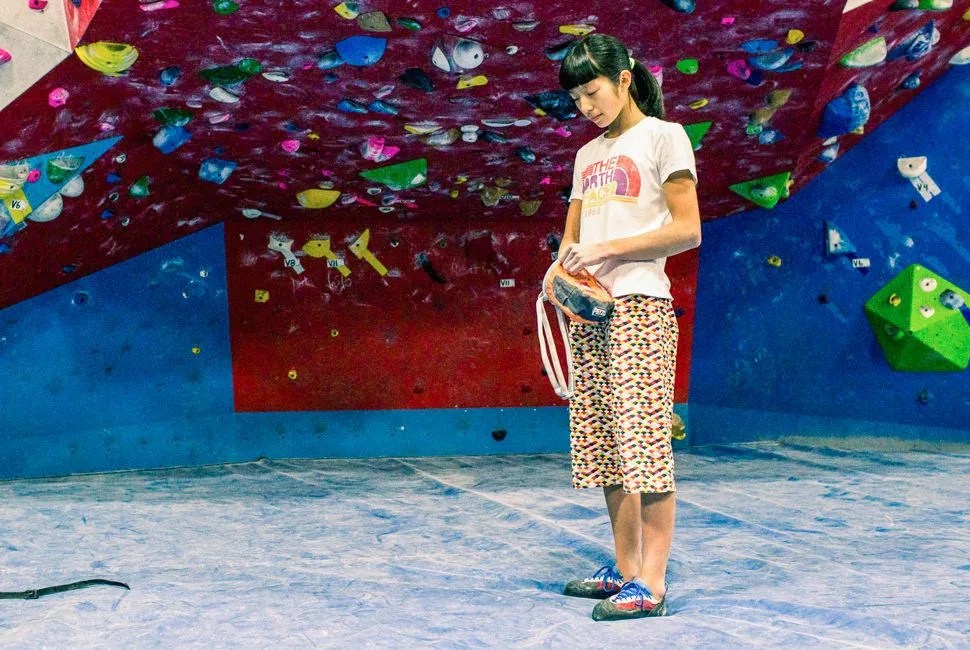

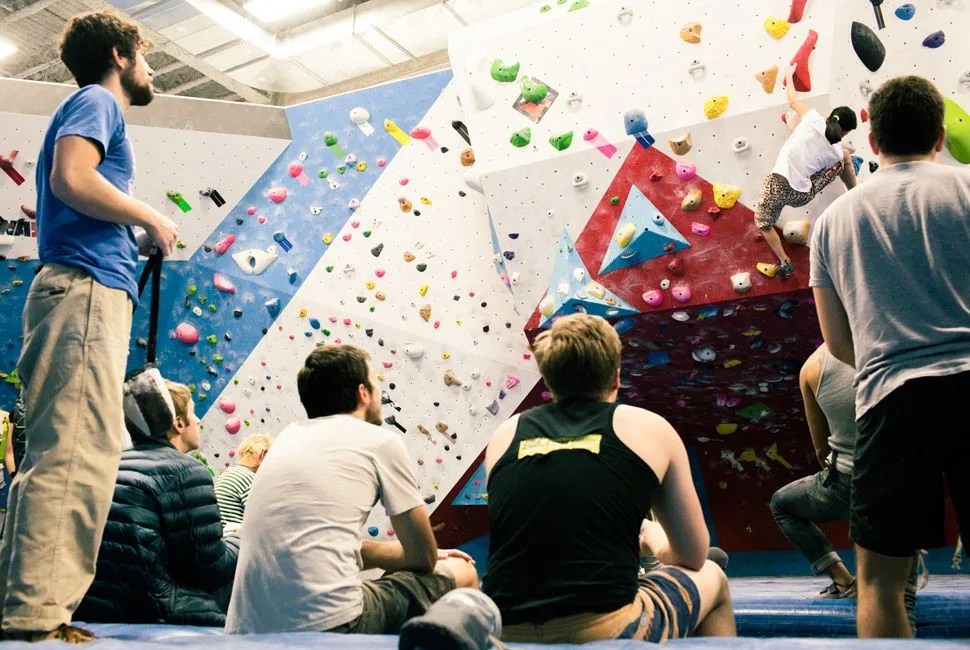

What you tend to notice first about Ashima Shiraishi is that she’s easy to miss. At five foot one, 90 pounds, she can get swallowed by a crowd. I kept losing and finding her again, my eyes scanning the soaring walls of a climbing gym in Queens, New York, where Ashima trains, and where a hundred or so chalk-dusted people were grunting in harnesses and Lycra on a recent Friday night.

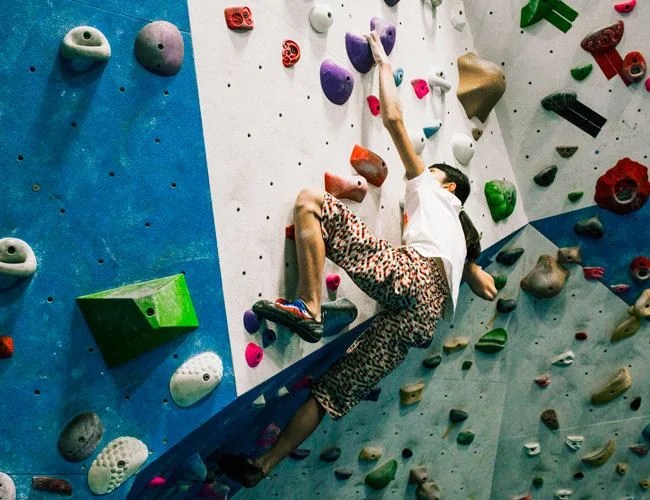

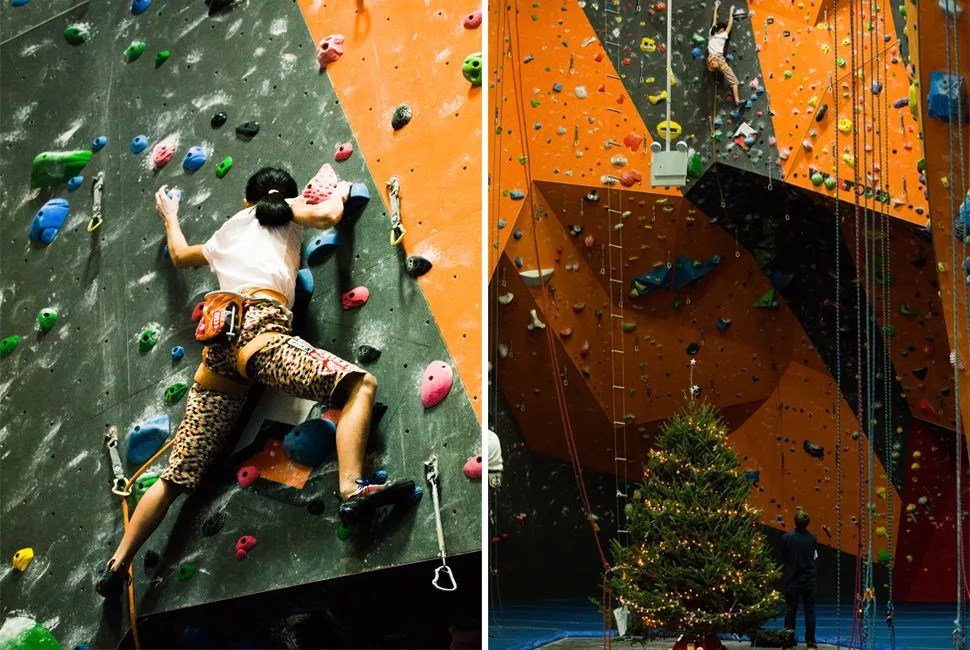

A good place to look for her was the 5.13a route, a zig-zagging 40-footer with a gnarly overhang about midway up, by far the hardest climb in the gym: you’re horizontal for a quarter of it, the ground a microsecond plunge away, and then have to pivot midair and swing yourself vertical again, up-and-over the lip, before finishing an ambling line to the top. It’s the kind of route that few climbers can do, as it requires intricate footwork and balance and insane finger-strength on unimaginably thin holds, and probably more so than that, an almost irrational degree of faith. Some rock climbers try their entire lives to “send” a 5.13a. Ashima, who at age 14 is one of the best climbers alive, first conquered it when she was seven.

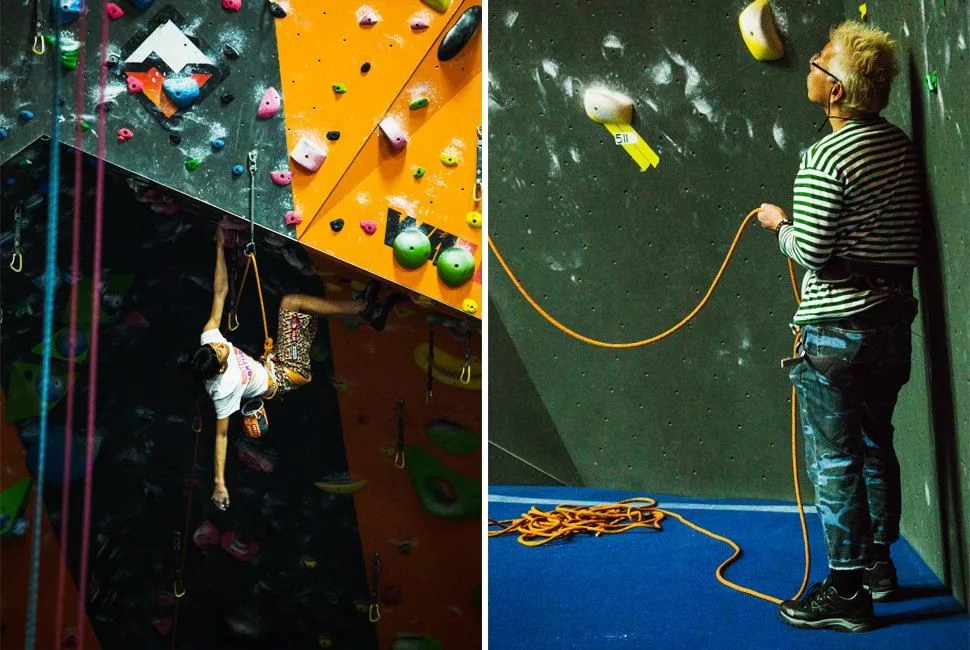

Nobody else was touching the route when I found her there, staring up at the pylon-orange walls. Friday was a “soft” training day for Ashima — she had a competition on Saturday (the ABS Youth Regional Championship, which she won) — and was here mostly to stay loose. With her dad, Poppo, belaying, Ashima squirreled right up the 5.13a. I timed her on my phone: it took 3 minutes. The climb didn’t appear to tax her in a respiratory sense — I don’t think she even opened her mouth except to chomp a rope while clipping-in — and she wasn’t up there long enough to break a sweat. A crowd gathered; camera phones came out. When I asked a woman among the photo-takers if she’d ever attempted the route, she looked at me sideways, a hand covering her mouth. “Of course not,” she snorted.

Something else you notice right away about Ashima Shiraishi is her wingspan. A person’s “ape index” is their arm length relative to their height. Olympic swimmers and pro basketball players tend to have high ape indexes, i.e., arms longer than they are tall. Michael Phelps has an ape index of 1.06; Rajon Rondo’s is 1.11. Ashima’s ape index is similarly advantageous. When one of her arms swung free on the climb, it had a Mr. Fantastic kind of elasticity to it — not freakish but borderline, somewhere between a ballerina and a longshoreman.

After rappelling down from the 5.13a, she climbed it again from another angle — two minutes, 51 seconds — before making her way to the bouldering walls, where some brawny guys in tank tops were struggling on a v11 roof problem a few feet above the ground. They kept falling, thwacking the mattresses and huffing off. Ashima waited her turn, then made quick work of the v11, sailing diagonally under it and then tacking into the air. For a moment, it seemed that gravity was another phenomenon altogether when applied to her. Cresting the top, she leaned back and looked toward the ceiling, as if wondering how much farther she could climb.

At just 14, Ashima has spent more than half of her life climbing, much of that at the sport’s highest level, and she seems to already be running out of challenges.