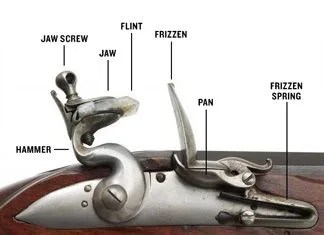

Marin le Bourgeoys created the flintlock mechanism between 1610 and 1615 while serving as the Valet de chambre (a job title close to a lackey but with a higher potential for upward mobility) for King Henry IV. Pulling the trigger of Bourgeoys’s creation released the hammer, which held a sharpened piece of flint that struck a piece of steel called a frizzen, flicking it back and creating a shower of sparks that lit a small pan of powder,

Copyright Oleg Volk

Copyright Oleg Volkwhich subsequently traveled through a tiny hole in the barrel and lit a larger charge of gunpowder, the explosion of which shot the lead ball through the barrel and toward its target. Here was the original Rube Goldberg machine — but as it was slightly less unwieldy and inconsistent in firing than its predecessors (doglock, matchlock, wheellock mechanisms), and therefore more deadly, it was soon in use on the weapons of the 17th and 18th centuries, first in muskets and then rifles. In America, the most famous forms of these were known as Kentucky or Pennsylvania long rifles and were used to accurately kill small game, and later British soldiers and officers during the American Revolutionary War. By the mid-19th century a caplock system made the flintlock obsolete, though they persisted among the lesser-equipped; during the first year of the American Civil War, Tennessee had over 2,000 flintlock rifles in service.

Today, the M249 squad automatic weapon can fire 1,000 rounds per minute and the M40 sniper rifle can hit targets half a mile away; even a standard hunting rifle shooting .30-06 cartridges can hit targets up to 500 yards away. And yet le Bourgeoys’s weapon lives on. It’s not because the flintlock rifle competes with modern weapons. Hunters and enthusiasts who continue to use flintlock rifles admire them as intricate machines and works of art; they use them to access the special, lengthier hunting seasons that most states offer, during which the woods are much less crowded than during normal rifle season and game is under less pressure from hunters; they appreciate the challenge of killing an animal with such a weapon, just like American and European hunters did hundreds of years before.

That challenge is not hyperbole. To use a flintlock rifle effectively, one must become a master at two processes that are at first clumsy and arduous: loading and firing. It’s not ripping open powder cartridges with your teeth and slamming home a ramrod like you’re in The Patriot. To become a skilled flintlock hunter, you must spend time both on the range learning not to flinch as explosions go off near your nose and honing the combination of ammunition and powder.