14 photos

“Our job is to keep free people from the cold, right?” Spencer Orr, VP of design & merchandising at Canada Goose, says, sitting in the front office of their Toronto HQ, adjacent a foyer lined with famous people wearing famous jackets. There’s Laurie Skreslet’s pink expedition jacket he wore in the first Canadian ascent of Everest, sitting opposite a photo of Kate Upton on the cover of the 2013 SI Swimsuit Edition in bikini and a white Chilliwack bomber. “Of course,” Orr adds, “cold is relative.”

MORE ELEMENTAL PROTECTION: Best Down Jackets | Best Lightweight Down | Best Rain Jackets

Canada Goose, manufacturers of hearty outerwear from The Great White North, obsess a lot over this word, “cold”, and creating its opposite, “warmth”. The battle of body heat versus nature runs deep in their blood, their land, their company history. For starters, Canada Goose manufactures every jacket on native soil, a land that’s half covered in permafrost and spends a good part of the year frozen. As for industry roots, the company, which began in 1957, introduced in 1972 a very special tool that triggered a monumental shift in the production of warm-weather wear: the down-filling machine. David Reiss, the father of CEO Dani Reiss, invented it. These days, Bain Capital’s invested in the majority stake of the company, and Canada Goose has expanded their internationally distributed line from Arctic expeditions all the way down to something to keep you dry on your next rainy-day walk. As Orr explains, “You can be cold when you’re wet.”

That’s the plain Xs and Os of Canada Goose: keep people warm despite the elements. But a better way to understand the company, from a perspective that’s closer to their heart, is to look at their pièce de résistance, the Snow Mantra. The parka has a penchant for showing up near the poles, and it’s been standard issue at McMurdo Station in Antarctica for years. It’s a down-filled beast equipped with a removable coyote fur ruff on a 3-way adjustable tunnel hood. The coat’s base settles somewhere mid-thigh. It has shoulder grab straps and reflective stripes and high-pile fleece to protect against wind. It’s known as the warmest coat on earth. It’s also arguably the toughest.

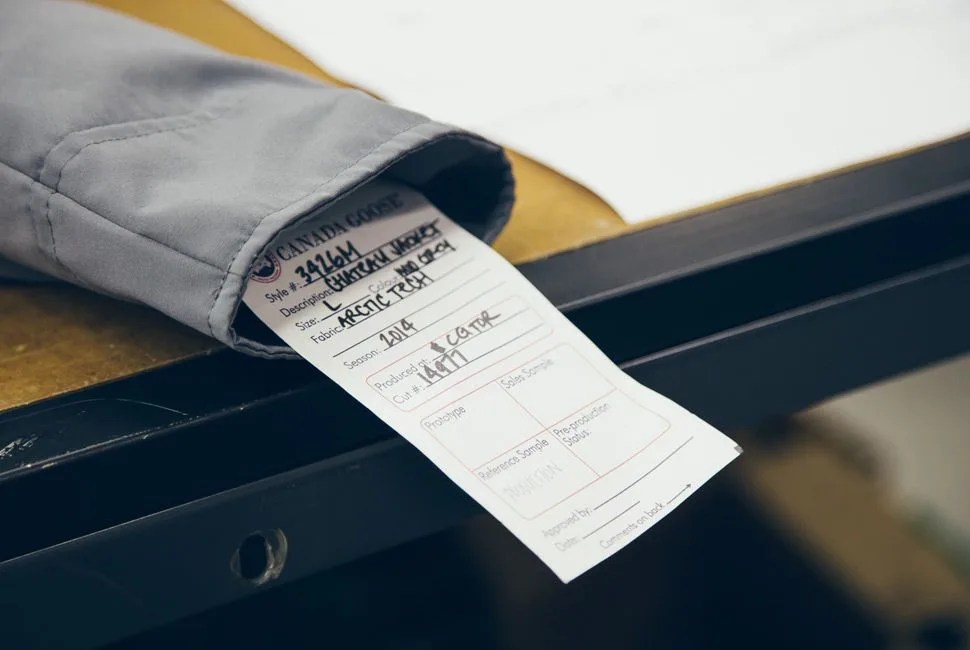

Rows of seamstresses sit with jackets under the needle. Off to the side fabric is cut, separated, organized, and tagged. The down room fills interior panels with feathers and clusters, all calibrated to the jacket’s use.

That, Orr says, is the pinnacle, and everything else trickles down from there. This is a utility apparel company, whose first clients happened to spend most their time in sub-zero temps. All Canada Goose jackets live in this industrious vein, from the award-winning Hybridge Lite (first developed for endurance runner Ray Zahab’s run through Siberia) to Upton’s Chilliwak (originally not for supermodels, but rather for northern bush pilots, who needed warmth on near-Arctic flights).