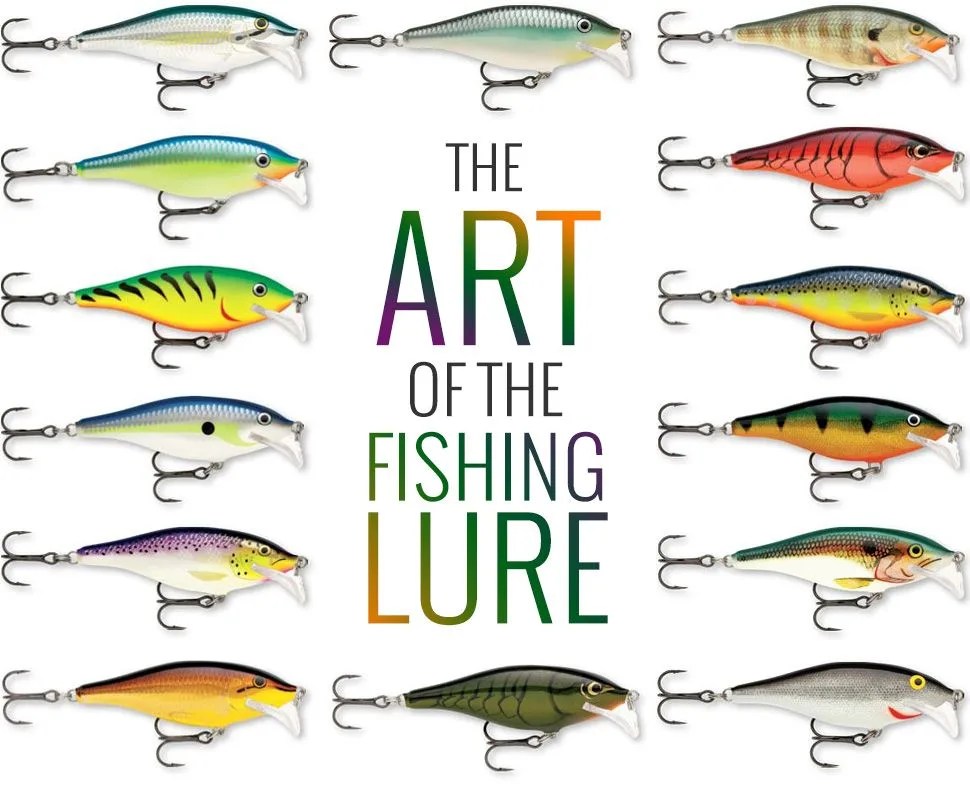

If any item holds special mysticism among fishing gear, it’s the lure. Some anglers spit on them for good luck; many have favorites (my dad and I still call one spinner, which will be kept secret to protect innocent fish, our “secret weapon”); rules abound for their use, like “light on dark days, dark on light”. Or was it vice versa? There are spoons and buzzbaits, tubes and cranks, jitterbugs and streamers (and dry flies, wet flies, and a million other flies) to choose from. It’s a lot to keep track of.

It’s understood that at their basic level, lures are deceptions meant to replace live bait, which are hard to gather and often expire prematurely, escape or are used up before the day’s work is done. But beyond that, a surprising majority of fishermen don’t really understand lures — and in this vacuum, myths abound. So we spit on them. And worship them. And generally pick them from our tackle boxes without much sense of why they’re the right choice.

And the lures (the good ones, at least) tend to work, maybe not every time, but on the whole — which, given recent findings about the intelligence of fish, is more impressive than we might have realized. In a recent study, biologist Culum Brown found that “fish perception and cognitive abilities often match or exceed other vertebrates.” Turns out they don’t

have five-second memories. More like a year, and maybe more. Brown has even written that certain fish species like the wrasse show similar tool use to primates and corvids (birds).

Fishermen have long known that fish are often smarter than they. But the rest of us probably haven’t given the lures used to catch these clever creatures their due. In fact, the best lures are really works of inventiveness, science, utility and even art.

Of any fishing lures, those used by fly fisherman seem to most readily fit this impressive description. Fly fishing has been around for many centuries, and for as long as they’ve whipped a line back and forth, fly fishermen have tied their own special lures. They’re called flies, but they’re actually representations of