8 photos

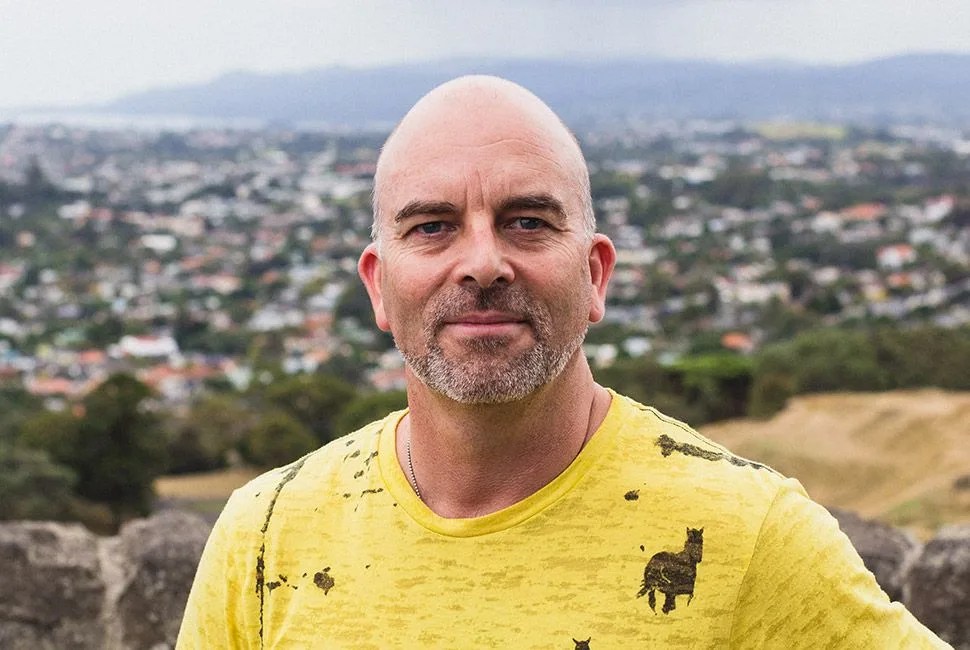

Cameron Douglas, in a yellow t-shirt screen printed with wild black horses running full gallop, slip-on shoes, tortoise-shell sport fishing glasses and a salt-and-pepper 5 o’clock shadow moving into full beard, does not look like a Master Sommelier. Somms tend to be button-up, iron-your-tie types — the title of Master Sommelier is the most prestigious title an expert on wine can attain. They don’t tend to be the type that drives a red sedan with sheepskin seat covers. But whether or not he fits the stereotype, Douglas is the man who knows NZ wine better than anyone else. If you want to talk New Zealand grapes, there’s no more authoritative opinion.

Douglas described his adolescent self as a “disgruntled high schooler” — and when he dropped out of high school, he went straight to work in the hospitality business. He did some cooking, learned about food, then figured out that to make it in hospitality you needed to specialize. This was the early ’80s. Through a connection of a connection, he met Evan Goldstein, a Master Somm, who encouraged Douglas to pursue the accreditation. He did, and after seven years of failing the examination — which, in his defense, has a 97 percent fail rate — he became the first and only New Zealand-born Master Somm.

“You hear people talking about New Zealand today — they know sauvignon blanc, bungie jumping, The Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit. What else do we do? The sailing, you know? Rugby and probably cricket?”

He also went back and got a degree in education. He now lectures at Auckland University of Technology, consults on six wine lists in New Zealand and creates the wine list for Matt Lambert’s Michelin Star restaurant, The Musket Room, in New York. He also writes for FMCG, Hospitality Business and is a monthly columnist for NZ Wine Growers.

Right now he’s steering his Audi A4 up to One Tree Hill, a vista point outside the city center of Auckland, while discussing the history of New Zealand wine. “New Zealand’s wine history is as old as 1819,” he starts. “And it really choked along for a while, and that’s probably an appropriate word because there was a lot of trial and error that went on, and what stalled a lot of it was the gold rush.”

“There was a gold rush in New Zealand?” I ask.