Ready for a walk on the wild side? A new whisky from Islay heavyweight Ardbeg has the usual intense peat and smoke notes, along with something else: weird and intriguing flavors created by wild yeast — by accident. Luckily, Ardbeg Fermutation, available to the distillery’s Committee members and whatever lucky Americans can track down a bottle, matured into something people will want to drink.

Though its creation wasn’t deliberate, Fermutation actually is a manifestation of something Bill Lumsden, head of distilling and whisky creation, had been noodling on for years, inspired by his taste in beer — or, rather, distaste for a particular beer. He hates Belgian lambics, yet could never stop trying them. “It was almost like a masochistic pleasure,” he says. Revisiting lambics repeatedly made him want to try replicating their fermentation process — which exposes wort to wild yeasts and microorganisms via open air tanks called coolships — for whisky.

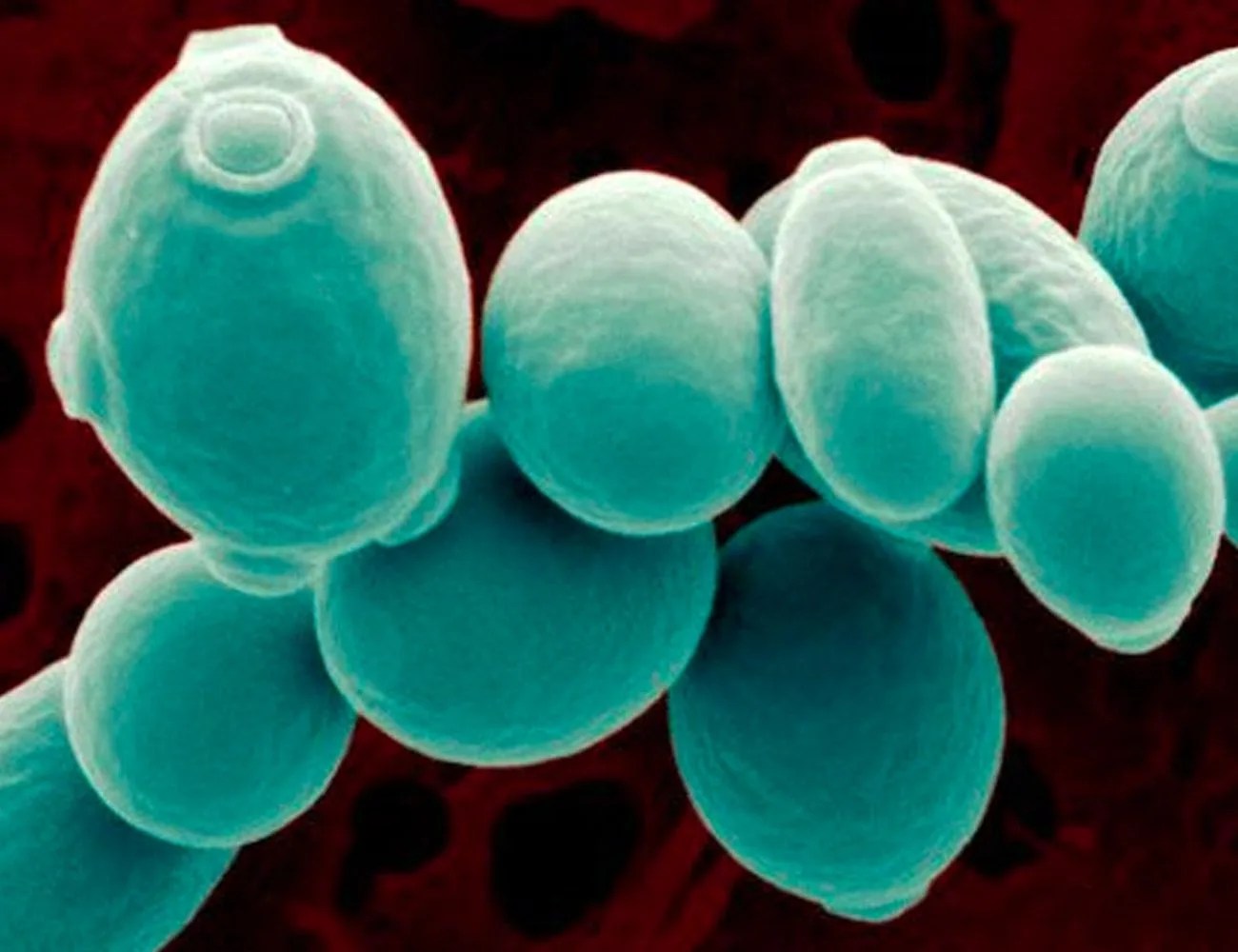

The idea was outlandish. In Scotland, a typical whisky fermentation takes two to four days; otherwise, Lumsden explains, “it goes mad and goes sour.” Plus, Scottish distilleries overwhelmingly use one type of generic distiller’s yeast, a strain designed for maximum efficiency. “[Yeast is] treated as a commodity in the scotch industry, which I find hugely disappointing,” says Lumsden. Flavor creation, in scotch, tends to focus on the stills and casks — not yeast.

Contrast that with American whiskey makers, who boast of their yeast strains as integral to the character of the bourbon and rye. Distilleries like Four Roses, which famously uses five different yeasts, and Jim Beam, which showcases a fridge full of its proprietary yeast on distillery tours, have visibly emphasized the importance of their chosen fermentation agent. The founders of Wilderness Trail, Shane Heist and Pat Baker, run another business called Ferm Solutions, offering literally thousands of different types of yeast to clients.

But in Scotland, no such yeast diversity exists, and the idea of exposing a wort to uncontrollable wild yeasts is unthinkable. Yet that’s exactly what Lumsden did, when Ardbeg happened to suffer a major equipment failure that required it to either destroy what was in the fermentation tanks — or let it rip for nearly three weeks.