15 photos

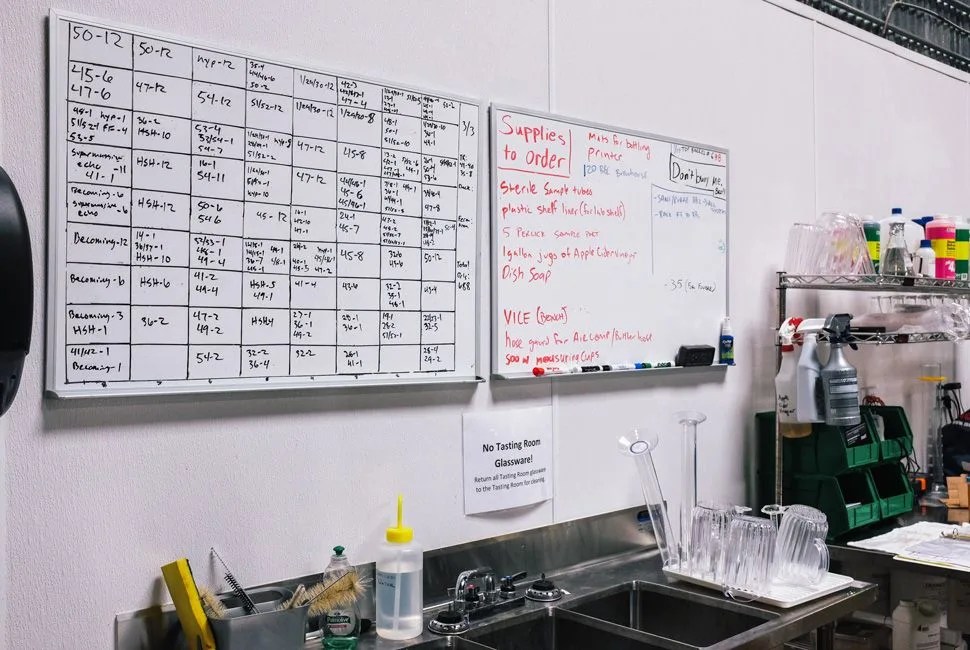

A few miles southwest of the Berkeley campus, in an area commonly referred to by locals as “The Flats”, a chain-link fence gives way to The Rare Barrel, one of the few breweries in America that love it when their beer goes sour.

“We like to joke that sour beer is the oldest style of beer in the world,” said Alex Wallash, cofounder of The Rare Barrel. “Brewers five thousand years ago didn’t know about microbiology, so their beer would automatically go sour if they didn’t drink it fast enough.”

Sour beer is an acquired taste, with a flavor profile that blurs the line between beer, wine, and cider. As Alex describes them, they’re tart like a handful of raspberries, acidic like a glass of wine and crisp like a flute of Champagne.

The style makes up such a small segment of the craft beer pie that it doesn’t even get listed when the Brewer’s Association collects information on beer styles. But as beer becomes increasingly popular, and drinkers demand more interesting and varied offerings, that’s changing. Technical seminars on sour brewing at the Craft Brewer’s Conference in Portland, Oregon have been among the most well attended, and at Boston’s Extreme Beer Festival, which has become something of an incubator for new brewing trends, lines for sours stretched across the room.

It’s also telling that despite the myriad oak barrels stacked to the ceiling of The Rare Barrel’s expansive warehouse and taproom, Alex and his cofounder, Jay Goodwin, still only have enough beer to open their tasting room three days a week. Bottle releases sell out on the same day; when they opened their online store to the Ambassadors of Sour, their opt-in fan club, they received such a flood of interest that their servers crashed. Twice.

Several popular breweries, including Sonoma-based Russian River, makers of the famed Pliny the Elder and Pliny the Younger, have sour programs, though few have gone all sour. That’s what makes The Rare Barrel so unique.