Brooklyn Brewery’s Steve Hindy and I were having lunch in Williamsburg when someone across the bar banged on the table and called out his name. “Steve!”

We both looked over, and everyone at the table had their glasses raised. “We love your beer”, one of them said. I asked Hindy if he knew them, and he shook his head no. He raised his glass in return, a big smile on his face, a touch of red coming through in his cheeks.

We were at the first bar that ever bought and served his beer, Teddy’s, just a few blocks from the brewery. We were talking about what differentiates “big beer”, the ones produced by corporate conglomerates like Anheuser-Busch InBev and MillerCoors, from today’s large craft breweries — Brooklyn Brewery, New Belgium, Sierra Nevada, Sam Adams, and Oskar Blues. He told me all about his grassroots beginnings, about how he, like all craft brewers that emerged in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s, went door to door with his beer, offering samples to bar and restaurant owners, while big beer had complete control of all the distributors. The interruption from the other table had given Hindy something else to point out — something else that set craft brewers apart.

“See”, he said, “that’s the main difference right there. [Craft brewers] are accessible, part of the neighborhood. How many Coors Light drinkers would be able to identify the CEO of MillerCoors?”

The spontaneous illustration highlighted one of the key aspects of the original craft beer movement: the concept of small brewers introducing locally made beer to their local neighborhoods. Even as today’s large craft brewers have blossomed and expanded, they have remain committed to where they grew up. But as Hindy and Co. begin to approach the age where retirement becomes a not-too-distant reality and the next generation of brewers begin to make a name for themselves, craft beer and its down-home roots are coming to a crossroads. As Kim Jordan of Colorado’s New Belgium Brewery put it, “There’s a fairly big shift happening as the founders of this movement transition out. There’s a new dynamic brewing that we haven’t seen before.”

In his book The Craft Beer Revolution: How a Band of Microbrewers Is Transforming the World’s Favorite Drink, Hindy traces the origins of the industry, attributing its initial spark to Fritz Maytag of Anchor Brewing Company (Anchor Steam) and, to Ken Grossman of Sierra Nevada, who started his brewery shortly after in the early ’80s. He puts himself, along with Jim Koch of Sam Adams (Boston), Kim Jordan of New Belgium (Fort Collins), Sam Calagione of Dogfish Head (Coastal Delaware) and Dale Katechis of Oskar Blues (Lyons), among others, in the second generation of craft brewers. These are the names that paved the way for what we know today as craft beer, an industry that has exploded in popularity over the last three decades, offering anyone with a hope and a dream (and a whole lot of capital) the ability to start a brewery.

Here in 2015, those first and second waves of brewers are beginning to hand the baton to the third and fourth. Cities across America are flooded with young brewers fighting to be a part of the industry’s future, continuing to push innovation and create their own niches. But while the first and second wave solely battled big beer in a showdown of David versus Goliath — with David being the collective craft beer community — this third generation is now met by a new set of challenges. For the first time, craft brewers face considerable competition within the craft beer community itself, resulting in specialization like the industry’s never seen it before. Not only are there more breweries than ever, but the industry is also now attracting “startup brewers”, businessmen more concerned with making good money than making good beer. Pair that with the continued and intensified pressure of big beer’s attack on craft beer, and all of a sudden the future appears more dynamic and unsettled than ever.

Dog Eat Dog

Although the original brewers might not have been aware of it individually at the time, craft beer’s battle against big beer began with four altruistic cornerstones: first, to stand up against corporate big beer companies; second, to make high-quality beer; third, to create and support neighborhood breweries; and fourth, to get people to drink local beer. The first two are an absolute given, and are well documented in any history of the craft beer movement. The latter two, which pretty much go hand in hand, are indirectly apparent today from the way those initial craft brewers conducted business and campaigned against big, nationwide breweries. In Denver, for example, when the city rallied around its local breweries, Coors was certainly not considered one of them.

Interestingly, these last two points draw the most discussion among beer professionals while discussing when the “local” movement really began. Brewers agree that they are factors that are influencing the industry today, but not everyone was sold on them as part of the original movement. Sam Calagione of Dogfish Head believes that the first generation of craft brewers was about flavor and diversity and small brewers, but not necessarily about drinking local.

“I think drinking local is more of a recent component of it”, Calagione said. “In late ’70s and early ’80s, it was less about wanting to buy local as it was about wanting to buy something that was not a light lager, something that was not brewed by an international conglomerate. [The first generation of craft brewers] wanted the option for more flavor and diversity. In time, people began drinking them because they were local, but not in the beginning.”

The main reason to talk about locality is to understand an eerie situation in the craft beer industry as it now succeeds in the quest for national distribution. Walk into two liquor stores, one in California and another in North Carolina, and you’re likely to find the same craft beer regulars — New Belgium, Sam Adams, Sierra Nevada — right next to the big beer regulars of Budweiser, Coors and Miller. In the last few years, a number of breweries, including Oskar Blues, New Belgium and Sierra Nevada, have started secondary breweries in North Carolina to make distribution on the east coast more practical. No one can blame a business for growing, but at the same time, no one can blame a craft beer drinker who finds the idea of craft beer distributing nationally a bit unnerving — or at least a bit ironic — given the industry’s lifelong battle against big national brewers.

Although the craft beer industry initially stuck together as a nationwide community, that same camaraderie is being challenged today when it comes to the reality of limited shelf space and hard-to-access distribution networks. To put it simply, craft brewers are stepping on each other’s toes like never before. In North Carolina, for example, truly local brewers now have to compete with “newly local” brewers who have moved in and started secondary breweries. Going forward, small, truly local craft breweries are going to have to compete for local distribution rights with national craft brewers and national big beer.

“Before, it was ‘Hey Bro, we’re here in the trenches together, give me your hand, I’ll help you out’”, said the owner of one Denver brewery, who asked not to be identified, of the changing landscape of competition within craft beer. “Now, it’s ‘Hey man, I’m over here doing this, so you better keep up, better get your act together.’”

This is not to paint an entirely dark sky. Regardless of where your thoughts fall on the conundrums of competition, it’s an undisputed fact that craft beer has improved the quality of the beer available both locally and nationally. And most brewers — including those at the largest breweries — insist that expansion is not a quest to step on the toes of other craft brewers. Ken Grossman of Sierra Nevada said that regardless of how much expansion his brewery goes through, he will continue to create local experiences and keep his company within the family.

“We’re a family business through and through”, Grossman said. “My son Brian co-manages our North Carolina brewery, and my daughter Sierra is hands-on in Chico and at our tasting room in Berkeley. That tight-knit spirit shows itself in our brewery culture, too. If you come to our taproom in California or our taproom in North Carolina, those are no doubt local experiences. Our beer is made right there, and the food is sourced nearby, if not from our own backyard garden.”

“There’s a fairly big shift happening as the founders of this movement transition out. There’s a new dynamic brewing that we haven’t seen before.” – Kim Jordan

Jim Koch of Sam Adams, the craft beer industry’s first billionaire, has also found ways to stay local and give back. Each week, he meets with and advises start-up craft brewers as part of Samuel Adams Brewing the American Dream. He also supports the city of Boston with the yearly creation of the Boston 26.2 Brew, served on tap only in Beantown every April during the Boston Marathon with all proceeds going to charity.

Dale Katechis of Oskar Blues had an interesting take on expansion; to him, creating two local breweries to meet demand is better than creating one gigantic “beer factory”.

“Introducing your beer to people is super fun”, Katechis said. “Getting out and changing people’s minds one beer at a time became a mission at Oskar Blues. We found ourselves traveling far and wide doing what we love and still enjoyed the hell out of it. While looking at how we were going to grow capacity to meet the demand, we looked in the mirror and said, ‘What the hell, let’s go to another small town and try to build a similar cultural thing.’ That’s how we found ourselves in North Carolina riding bikes and brewing beer. Instead of building a big beer factory we decided it would be a hell of a lot more fun to build another smaller brewery in a small town with the quality of life we wanted for all of our people.”

Still David, Still Goliath

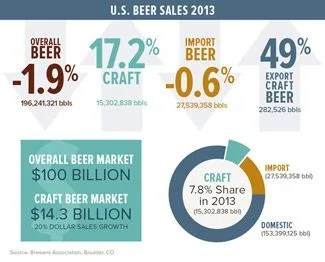

Despite how far craft beer has come, it still represents a very small percentage of the overall beer market. According to the Brewers Association, craft beer made up 2.6 percent of the overall US beer market in 1998. In 2013, craft beer was about 8 percent of the overall market. There’s good news and bad news in those figures. The growth has been tremendous, but more than 90 percent of the market is still non-craft big beer (78 percent) and imported beer (14 percent).

Big beer has always been craft beer’s main competition here on home soil. Big beer beat back the initial craft beer movement in the ’80s and ’90s by dominating the distribution network (remember, Hindy and co. had to go bar to bar trying to convince owners to put it on tap); for craft beer, loosening the stranglehold big beer had on distributors was the first big victory in increasing its market share.

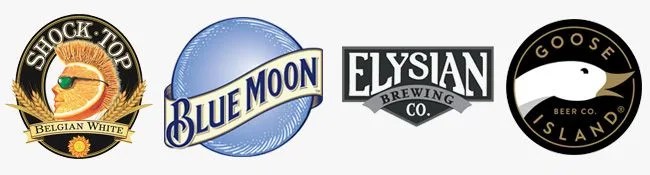

Big beer may now be on the defensive as it continues to lose business, but it certainly isn’t backing down. In fact, it has become even more creative in the ways it attempts to regain market share. In the ’90s, beer conglomerates began brewing what has become unofficially known in beer circles as “crafty beers” — that is, beers that look and feel like craft beers but are brewed by big corporations. For example, Blue Moon is brewed by MillerCoors, and Shock Top is a product of Anheuser-Busch InBev. More recently, these companies have cut to the chase and started to outright buy up craft breweries. In January, InBev bought Seattle’s Elysian Brewing Company, and in 2011, Chicago’s Goose Island. Jim Koch believes that the buyout of small craft brewers is the biggest threat to the industry and an avenue for the collapse of craft beer; Steve Hindy thinks craft beer has already come too far despite the best efforts of big beer to undermine its progress.

Opinions might be split about whether the buyouts can halt craft beer’s growth, but no one questions the fact that big beer’s stance as a buyer — one capable of making a brewer rich overnight — has planted a virus in the craft beer community. Several brewers expressed concerns that the newest generation of craft brewers, not unlike today’s technology industry, contains people who are more interested in making money than beer. They look to create “startup for-sale breweries” whose business plans are centered on quick growth, and the intention to sell is present from the very beginning.

“Some people now don’t see the industry as [the first and second generations of craft brewers] do”, said Kim Jordan of New Belgium. “They are getting in for money and are motivated to get out. That is a much different dynamic than those of us who got in for our love of beer.”

Big beer’s stance as a buyer — one capable of making a brewer rich overnight — has planted a virus in the craft beer community.

Businesses, even ones seeded from passion, still need to make money. So, is it naïve to suggest that it shouldn’t be a focus? Isn’t it possible for passion and economics to coexist? Chad Miller of Denver’s Black Shirt Brewing said that his beef is not with business who want to turn a profit – it’s about “brewers” with no real intention of being brewers. He’s seen a huge change in the way people approach him for advice over his 14-year career. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, prospective brewers would talk to him about their feelings, about how they hated their corporate jobs and how their real passion was making beer. Today, he said, people approach him wondering how they might cash in on a ballooning industry.

“[10 years ago] they would ask me how they could make beer for a living”, Miller said. “But now people come and ask me how many barrels I think they need to make to turn a profit and show investors their potential.”

His description of this new generation of “brewers” is disconcertingly reminiscent of something Steve Hindy said at lunch when I asked him to articulate the difference between big beer and craft beer. “These guys are playing with different sheet music”, he said of big beer corporations. “They’re in the business of making money, but we’re in the business of making beer.”

Thriving Specialties

The IPA is by far the best-selling beer style in today’s market, and, according to the Brewer’s Association, it continues to grow at a near 50 percent clip per year. It’s hard to find someone who doesn’t brew one, and the industry continues to push the style forward with new variations, such as double and triple IPAs that are taking hop contents to levels that were once unfathomable (to understand how drinkers’ palates have adapted, read up on the “Lupulin Threshold” theory as made famous by Russian River’s Vinnie Cilurzo). Yet while the IPA might lead the style pack for a long time to come, there are signs that both drinkers and brewers are looking past the style more than ever.

“You can’t zero in on one profile [of a craft beer drinker], and that’s what makes craft beer exciting”, Ken Grossman of Sierra Nevada said. “The demographics are changing, and while there are dedicated fans, there’s a wave of people just starting to dabble in craft beer. Common among them is an appreciation for variety and big flavor.”

“Today’s craft beer drinker is adventurous, local and loyal, but also looking for options”, Dale Katechis of Oskar Blues said. This means a widened range of beers from breweries, but it has also proven that swinging the opposite direction — toward extreme specialization breweries — can drive new creativity and build strong local fan bases. Specialization is not a new concept — The Alchemist Brewery in Vermont, for example, has brewed only one beer called the Heady Topper since 2011, and plenty of breweries have long focused specifically on Belgian- or German-style beers. But now more than ever, in a beer scene where a new brewery seems to open every other day, brewers are taking the idea of specialization to another level. Across the nation, brewers are beginning to stand out from the crowd by following their personal passions to an extreme, whether they relate to beer or not. For all the worry that new “startup for-sale breweries” serving crowd-pleasing beer are bestowing upon veteran craft brewers, this specialization movement seems to be rediscovering craft beer’s original passion.

Take, for example, Crooked Stave and Black Shirt Brewing in Denver’s River North neighborhood, which only brew sour beers and red-style beers, respectively. Or Trve Brewing in Denver’s South Broadway neighborhood, a heavy metal-themed brewery. These breweries have taken their passions to an extreme, evolving and focusing them in a way that craft beer hasn’t seen before.

“The decision to be a metal brewery was simply a decision to be myself”, said Trve’s Owner Nick Nunns. “I’ve been a metalhead my whole life and the brand is simply an extension of my own personality and the things I enjoy in life.”

“We wanted to answer to our own motivations”, Chad Miller of Black Shirt Brewing said. “We asked ourselves, ‘Are we going to be known as a Walmart with something for everyone? Or as a brewery that spends every waking moment chasing perfection?’ We’re not trying to live up to anything or follow recipes. We’re trying to do our own thing.”

This type of brewery has also proved effective amid craft beer’s increased competition. Nunn said his passion was first and foremost when it came to the decision to become a heavy metal brewery, but he does see the idea of specialization as a way to stand out, especially here in Denver and other saturated markets.

“Moving forward, I think it’s important for breweries to have a combination of both high-quality beer and a distinctive brand concept”, Nunn said. “At the very least, it’s incredibly important to have quality beer. A strong brand is only going to help you further.”

Another brewer with a bit more experience, Sam Calagione, had similar thoughts. “I believe that craft breweries have to be firing on three cylinders: Making world-class, quality beer, making it with world-class consistency, and making beer that is well differentiated”, Calagione said. “I think specialization is part of being well differentiated. You can say something like, ‘We’re only going to brew saisons using peppers from all around the world.’ And that’s your point of distinction, and if you do it really well you can be successful.”

Nunn and Miller both expressed a rightful anticipation that their respective themes would work against them in certain regards. For example, Nunn knew not everyone would dig his heavy metal approach. Miller talked about missing out on what he called the “Pilsner customer”, someone who simply wanted a standard beer. When I asked Kim Jordan of New Belgium for her thoughts on specialization, she touched on this very obstacle, saying that the strategy could end up limiting growth in the long run. But for both Miller and Nunn, the tradeoff was worth it in terms of their personal goals.

“I don’t think about success in terms of the number of kegs or the amount of shelves we’re on”, Miller said. “I think about success in terms of the smiles we see from our customers.”

Where Are We Headed?

As craft brewers continue to push and prioritize their national (and international) distribution networks, it’s not hard to imagine a world where the same craft beers are available in every state. This would signal a great success for craft brewing as an industry, but it brings up another huge issue that’s beginning to reveal itself: As once-local craft breweries grow into national craft breweries, will they become too powerful? Will they devour shelf space across state lines and push out still-local craft brewers the same way big beer used to do to a then-young craft beer industry? Walk into any store across the country, and you will find that is already happening. Could the next battle be one over shelf space that weirdly positions big beer and national craft brewers against everyone else?

“Distribution [shelf] space is very limited”, Miller said. “It’s all well and good between brewers until it comes time to distribute. That’s when elbows are noticeably sharper.”

“I believe in the integrity of the craft beer drinker.”

– Sam Calagione

But what’s at stake is truly bigger than distribution battles. As competition continues to rise within the craft beer industry, many questions remain unanswered. Will brewers remain true to the morals of the founding fathers where passion was prioritized, or will they trend towards the big beer mentality, where sales potential dominates their motivation? Will “startup for-sale breweries” continue to appear, sell out, and land craft in the lap of big beer?

“I believe in the integrity of the craft beer drinker”, Sam Calagione said. “They know that if they buy fake craft beer [that’s produced by big beer companies], then that’s all they’ll eventually have left. If someone doesn’t care who makes the beer, and they want to put their money into big conglomerates, that’s their prerogative. But if you are about your local beer community, then you should prioritize buying from local communities and local brewers.”

Today, when beer drinkers approach the beer aisle, or go out with friends, they have more options than ever from both local and national brands. Everyone agrees this is a very good thing; how we got here is no mystery. Beer drinkers demanded variety, and they backed it up with their dollar, allowing the Sierra Nevadas, Sam Adams and Oskar Blues of the world to stand tall next to big beer. Those drinkers and breweries have, in turn, paved the way for the future generations of craft brewers, giving them a blueprint of the battlefield. But what will the next generation’s blueprint look like?

Despite the daily evolution happening within craft beer that makes predicting the future landscape a tough thing to do, Calagione is correct in that one thing, something that has remained true since day one, is clear: just as consumers gave birth to craft beer initially, so too will they be the ones to decide its fate.