The craft beer boom has shown few signs of slowing down. Every week — every day, really — a new brewery opens somewhere in the United States. And they are thriving, even in far-flung locations like Anchorage, Alaska or Montague, Massachusetts.

But the landscape continues to evolve. Some of the country’s most well-known craft breweries, including Lagunitas, Anchor Steam, Founders, Ballast Point and Goose Island, have been swallowed up by big conglomerates. All the while, the market becomes increasingly saturated with young breweries that champion the virtues of small, local and fresh.

With that growth — 635 new micro breweries in the United States in 2014, and another 433 in 2015 alone — speed bumps are destined to arise. According to a recent report, craft beer sales have fallen below a double-digit increase for the first time since 2005. Recently, a chink in the armor occurred when Stone Brewing, one of America’s biggest, most iconic craft breweries, laid off around 5 percent of its workforce. About 60 workers lost their jobs, some of whom had been at the company for more than 10 years. With that news, we called craft breweries across the United States to get a pulse on where craft beer is, and where it’s going. Here’s what they had to say.

Editor’s Note: The following responses have been edited for clarity and length.

Jen Kimmich, Co-Founder, The Alchemist

With Heady Topper — the double IPA that previously led RateBeer’s Top 50, a list ranking the best beers in the world — The Alchemist has become one of the most storied and beloved breweries in the country. It recently opened a brand-new, state-of-the-art facility in Stowe, Vermont, to increase production of Focal Banger, an American IPA, and other seasonal releases.

Q: In a press release, Stone cited the “onset of greater pressures from Big Beer as a result of their acquisition strategies, and the further proliferation of small, hyper-local breweries” as cause for restructuring. Were you surprised?

A: We do see friends that have bigger breweries and we see the beer pile up and the stress they go through. It’s hard when you try to compete regionally. Whether it is draft lines or shelf space, there is only so much the market can take. There are more breweries than Stone that are going to be pulling back.

Q: What lessons have you learned since opening the brewpub in 2001? That was at the beginning of this huge beer boom. What has changed since then?

A: If you focus on your local community first everything else will work out. That has really proven to be true for us. We were never placing ads in beer geek magazines — that was never our thing. You can’t put everything into beer tourism. It’s too much to risk.

Q: Do you think beer will become more localized? What about these larger, bigger craft brewers?

A: People will support you if you’re local, and they know you, and you support your community in various ways. I think you need to have good beer, but it doesn’t need to be earth shattering. Once you make the decision to distribute your beer and be regional or national or even international, then the whole game changes. Then you’re really competing for shelf space and you’re competing for draft space and the stakes are a lot higher.

Q: Is there a future for new breweries with those kinds of aspirations?

A: I don’t think there is much room for big breweries like that. Those are the breweries that are going to suffer. I think the trend we’re seeing is really smart, an observation of, “Boy, there are so many breweries that it’s hard to get contracts with distributors, and it’s hard to get enough hops to make all this beer.” There are all these barriers, so I think [brewers] are just naturally realizing what is feasible and what is not as a startup.

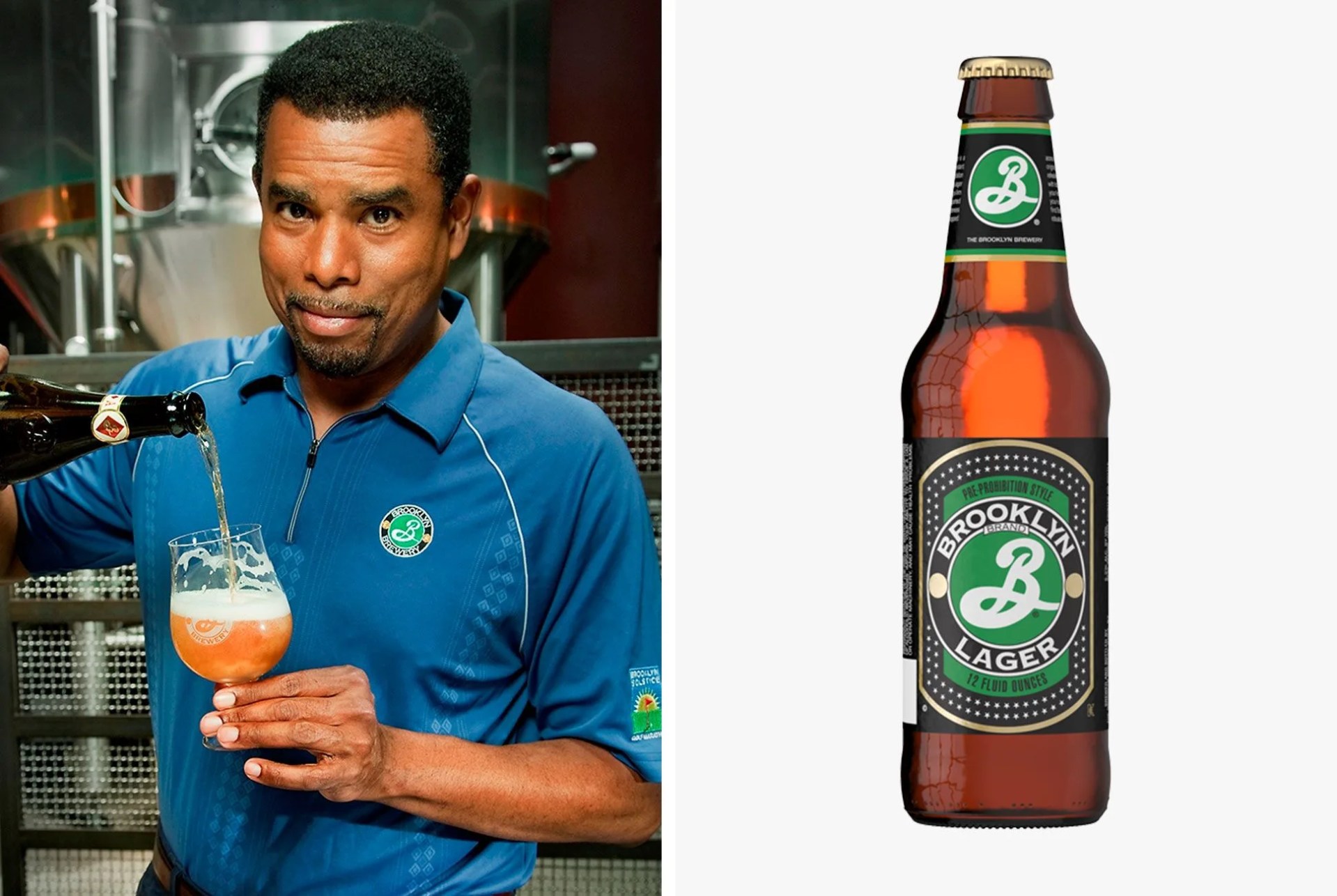

Garrett Oliver, Brewmaster, Brooklyn Brewery

Brewmaster Garrett Oliver — a celebrated author and “Honorary Beer Academy Sommelier” — has seen it all in the nearly 30 years he’s been brewing at Brooklyn Brewery, so he’s not surprised that the craft beer bubble has potentially begun to slow its staggering pace.

Q: Has the craft beer bubble finally burst?

A: I think it can’t be too surprising that any segment of business that has grown at the ludicrous clip that craft brewing has over the last 20 years would eventually start to experience a slowdown of that growth. I think that it bears paying attention to that it is only a slowdown of from explosive growth to fast growth. If any of us could possibly find an investment that grew 7 or 8 percent every year we’d be golden, and that is what is going on still in craft beer.

Q: What about the surge in small, local microbreweries across the States? That’s your competition.

A: There is no doubt that the existence of a huge number of local players definitely provides headwinds for some of the larger breweries. But Brooklyn Brewery is definitely an entirely unique creature among craft brewers. About 50 percent of our sales are actually overseas. We are a very international company and we always have been, or at least since the beginning of the company, back in 1988, ’89. Despite our size we are only in about 27 states. Eventually, I am sure we will fill out the rest of the country, but we’re not in a huge hurry.

Q: Why expand to Europe instead of other parts of the country like, say, the West Coast?

A: There are no East Coast breweries showing interest in building on the West Coast. A lot of people don’t realize this, but part of the reason people are building their breweries out east is because they were tired of trying to ship beer over the Rocky Mountains. When you have to basically send some heavy-ass beer through a mountain pass by truck or train, that is a lot of energy and a lot money. Never mind the miles in between. Sending something by the ocean is much, much cheaper than sending it by road or mail.

Q: How does a brewery like yours stay relevant in the ever-changing landscape of craft beer?

A: Brooklyn Brewery has been a pioneering brewery, and a brewery that has created entire movements for decades. We invented things like collaborations, for example, and beers based on cocktails — all sorts of areas that later became trends.

Today, we have one of the biggest barrel programs in the country; we have over 2,000 barrels in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. At the same time, we spend a lot of time and effort paying close attention to quality to make sure that when people do go out and get our beers, even a familiar beer like Brooklyn Lager, that they taste exactly the way they want and expect them to.

Q: What do you see happening to craft beer in the future?

A: I look at craft beer in a broader context than beer. To me craft beer is just part of the arc of recovery of American food, and it goes hand in hand with bread and cheese and chocolate and coffee and cocktails and wine-making and people learning to make real stuff again. I think that is what is going on, and I think that there is no real end to any of that in sight.

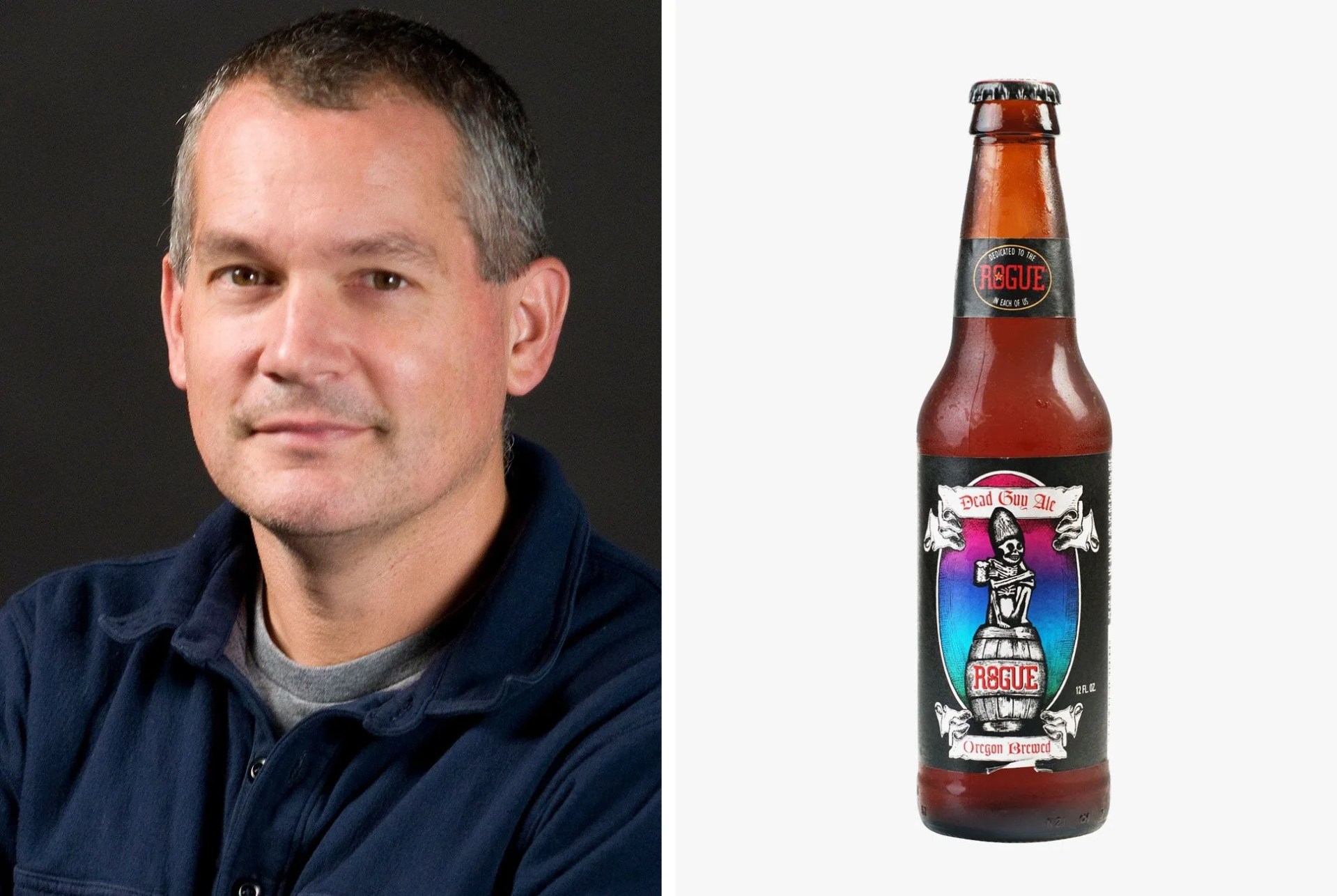

Brett Joyce, President, Rogue Ales

Jack Joyce helped launch Rogue Ales in 1988 in Ashland, Oregon. Today, his son Brett Joyce is in charge of one of the most influential breweries in the country, specializing in unpasteurized ales made with all-natural ingredients, including a proprietary yeast known as Pacman.

Q: What has changed in craft beer since you started working at Rogue?

A: It’s changed a lot in five years. The raw number of breweries out there is remarkable. Think ten years ago, it was more ma and pa; it wasn’t the big business that it is it today. The overall quality of the competition is awesome. The quality of the beer, the quality of packaging, the quality of the branding and the quality of the owners and staff of the breweries. For us, it forces us to raise our game. You have to be a lot better now, up and down your organization to be successful and compete.

Q: You’re one of the legacy craft brewers now. What do you think of your position in the market?

A: Legacy is a nice way of calling somebody old. I don’t take the wrong way. We understand that and we think about it this way: You can’t do anything about your age, but we want to be the cool uncle. We don’t want to be the legacy brewer that wears mom jeans and white New Balance.

Q: What do you think about the trend to buy local that has evolved recently?

A: I’ve been talking about that same farmer’s market trend for a number of years now. The reality is if you’re outside your home state or market, you’re not going to be local. You can only be local in one place, maybe one state if you’re lucky. Beyond that, you have to understand your position and work hard to figure out how to compete, and how to justify taking a product to a market that might have 20, 50, 100 breweries that are going to be more local. That is always the challenge, and it’s not going away.

Jason Perkins, Brewmaster, Allagash Brewing Company

Perhaps no domestic brewery has done more than Allagash Brewing Company in Portland, Maine, to promote the majesty and grace of Belgium’s beer traditions stateside. For brewmaster Jason Perkins, quality and consistency will be what separates good breweries from great ones.

Q: What have you seen change in the craft beer scene in Maine?

A: Portland was fairly early on the craft beer scene in the US. Not the earliest by any means, but D.L. Geary started in 1983, so that was fairly early in the microbrew scene, as they called it back then. When I started [at Allagash] in 1999, there were, I don’t remember how many breweries in the state. Ten, maybe fifteen if you included the brew pubs. There was definitely a scene at the time, but not a lot of diversity. A lot of the breweries in the state brewed English-style beers.

Even though there was some market for craft beer, it was a struggle for us to sell the beers we were making. No one was doing what we were doing at the time. We started with Allagash White, and that was really all we sold for a little bit. It kind of felt like an uphill battle.

Q: Has your focus changed? Or are beer drinkers just more open to new things?

A: We’ve had a pretty specific focus since the beginning with Belgian-style beers. That’s a pretty wide range of styles of course, but a big part of that tradition of brewing is experimentation and beers that fall out of styling guidelines. Luckily the consumer has been really excited in beers that stretch the limit of style. It’s allowed us to keep doing the stuff we were already doing and expand it even more. That’s been with more and more wild fermentation, more and more barrel usage. We keep innovating and stretching the limits of style.

Q: What is the way forward for breweries like Allagash in a crowded market?

A: We’ve had success with keeping our head down and staying focused on what we do. Luckily we have one singular owner who is very much behind quality and innovation. We invest tremendously in our quality program at the brewery. I feel like by not opening new markets and by not chasing down new styles, we’ve been able to stay focused on what we know and what we feel like we’re good at.

Rob Burns, Co-Founder, Night Shift Brewing

The youngest brewery on this list, Night Shift Brewing in Everett, Massachusetts, is focused on staying local, despite the rapid growth it’s experienced since being founded in 2012.

Q: What has the growth been like for Night Shift?

A: We’ve definitely grown way faster and bigger than we ever imagined. I think in our first year of business we sold about 200 barrels of beer; this year we will do right around 10,000. We have been more than doubling year over year in terms of production. Our [original] business plan stopped at 10,000 barrels and we thought we’d get there somewhere around year ten. So we’re kind of making it up as we go, to some extent.

Q: What kind of changes to the business plan have you had to make?

A: Having a taproom was never in the original business plan. That’s become a huge part of our business that we didn’t expect. We recently expanded the taproom to add in another almost 4,000 square feet of space. Launching a distribution company was definitely another thing that wasn’t originally in the playbook, but has kind of come to fruition.

Q: What was the reason behind self-distribution?

A: The original reasons were twofold. We were so small that we couldn’t afford to give away any margin to a distributor, so we wanted to sell it at the highest price point possible; and then it was that we didn’t trust any distributors in the area due to the franchise laws in the state, which basically means once you sign with somebody, you’re stuck for life.

Q: Where do you feel you fit into the brewery world?

A: I think we’re one of the bigger breweries out there now in the state. Nationally we’re right around the top 10 percent in terms of volume, which is kind of crazy, but I don’t think we ever want to be like Stone, where we have a national distribution footprint, where we’re in every single store or every bar. We’re definitely looking to get a little bit bigger, but not necessarily to the same extent as these other guys.

Q: So why stay local?

A: I think beer is a perishable product. It tastes best when it is fresh, and you can only control that within a certain radius. I think that has been one of our advantages, getting fresh beer to the market, which is something that somebody like Stone can’t compete with. By the time their product gets to the store shelf it’s already older than any beer of ours that is on the shelf.

Q: Where do you see craft beer going?

A: I think we’ll see fewer national brands. Fewer Stones, fewer New Belgiums, fewer Sierra Nevadas, and more strong local, regional players. I think having access to a taproom is really key to keeping customers interested and having a connection to the brewery. Our kind of goal is to be a strong player in New England. In terms of size and volume, we’re not sure.

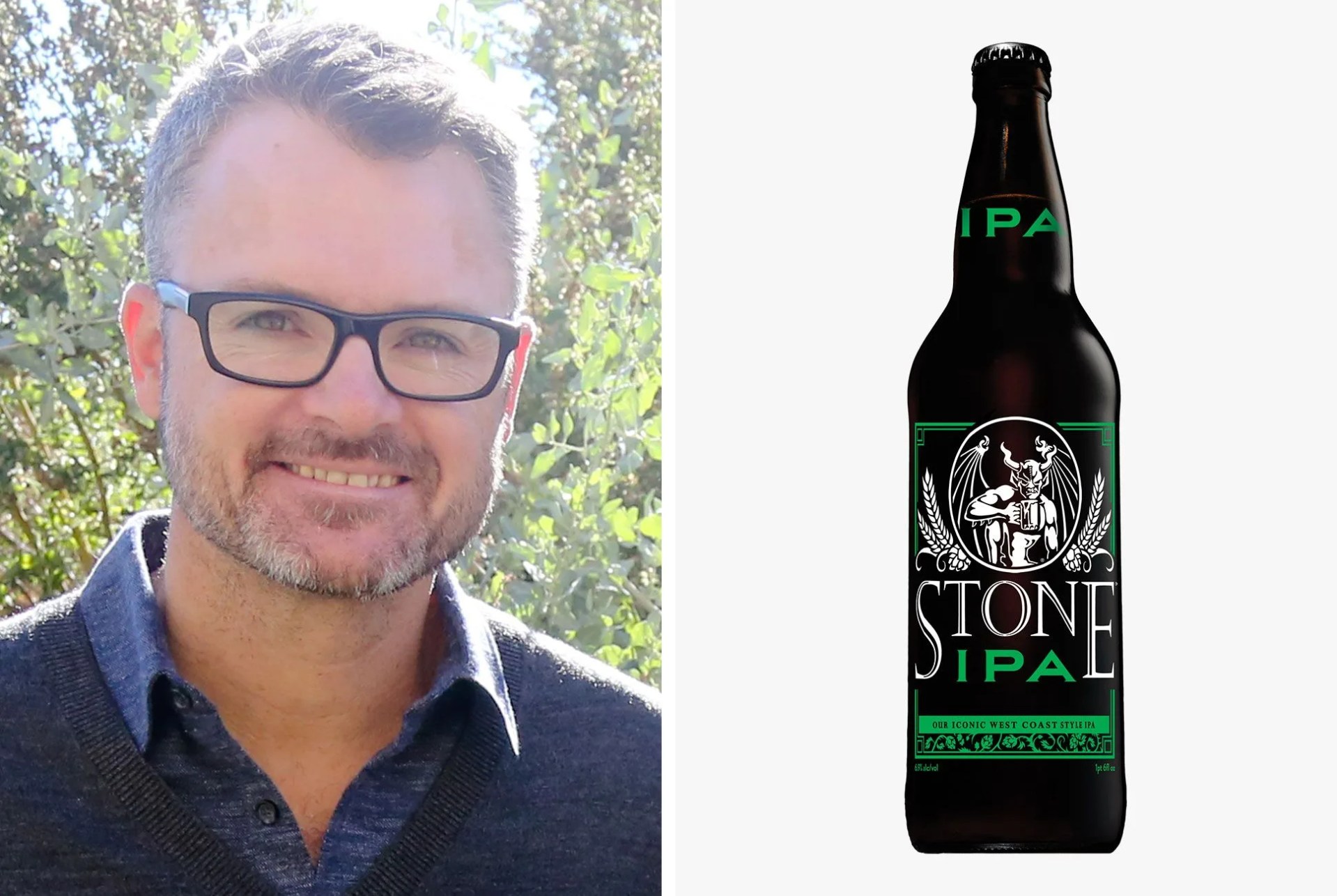

Dominic Engels, CEO, Stone Brewing

Founded in 1996 in San Marcos, California, Stone Brewing has grown to be the largest brewery in Southern California. It’s also employees more than 1,200 workers, despite recent layoffs, making it one of the largest craft breweries in the world, with secondary locations in Richmond, Virginia, and Berlin, Germany.

Q: Many of the larger craft breweries have been bought up by bigger macro-breweries, while Stone has held steadfast in the belief that it is craft and doesn’t want to move on. Is that something it still believes in?

A: Absolutely, unequivocally, yes. That’s something that is absolutely something we won’t ever trade off. We are defining the future of craft here at Stone and by virtue of us not relenting on that fact of being anything but independent.

Q: So what’s next for Stone?

A: We’re igniting a next phase — Stone 2.0 if you will — where we want to prioritize our employees above all others. Then we’re going to put the beer second, and the experience third.

The next step for us is growing into some recent investments that we’ve completed. That means bringing [the Berlin brewery] to fruition. It also means, having completed an East Coast brewery, making that a hub for our East Coast craft fans to have fresh beer and participate in Stone.

Q: In light of the layoffs, what does that mean — putting your employees first?

A: We’re the largest employer in the craft beer segment with 1,200 employees, and we did have to recently restructure about 5 percent of our workforce. To me, I look at that as a course correction with all due respect to those folks, because many of them had been long-tenured employees we still consider part of team Stone. We had to make sure our growth trajectory and our cost trajectory were in line.