At the Brooklyn Kitchen in Williamsburg, past the registers, past the display of cast iron, past the $850 Big Green Egg and a display case full of local meats and premium cheeses, is half of a 300-pound pig stretched out on a cold metal table. Light streams in from a skylight in the high ceiling as butcher Scott Johnson cuts him into smaller and smaller — and then recognizable — cuts of meat. “People associate this with giant blades, but it’s mostly done with the tip of a very sharp knife,” he says as he pushes the spinal cord out with an index finger.

The Brooklyn Kitchen opened in 2006 when Taylor Erkkinen and Harry Rosenblum wanted to sell the kind of well-made cookware they searched for but couldn’t find in their own neighborhood. Their vision then expanded to meat, cheese, canning, grilling and, after an expansion added more space, classes. The most involved of these classes is full-animal utilization, a term which first entered the foodie zeitgeist after Fergus Henderson elevated the millenia-old practice to make it modern, and trendy. And now, over a decade later, it checks all the right boxes to make it popular, even within the confines of an urban setting; Brooklynites can get food that’s local, that they can cook themselves and that forgoes animal waste.

The gist of full-animal utilization is that, as the name implies, more or less every part of the animal is used. If it’s good-looking meat and fat, it’s used for commercial cuts. If it’s a bit uglier, it gets ground in to sausage. Bone is used for broth. The tail, for dog treats. The only parts of the pig not used are the spinal cord and glands, which “make the pig stock cloudy,” Johnson says as he tosses the white cord into a mostly empty waste bin.

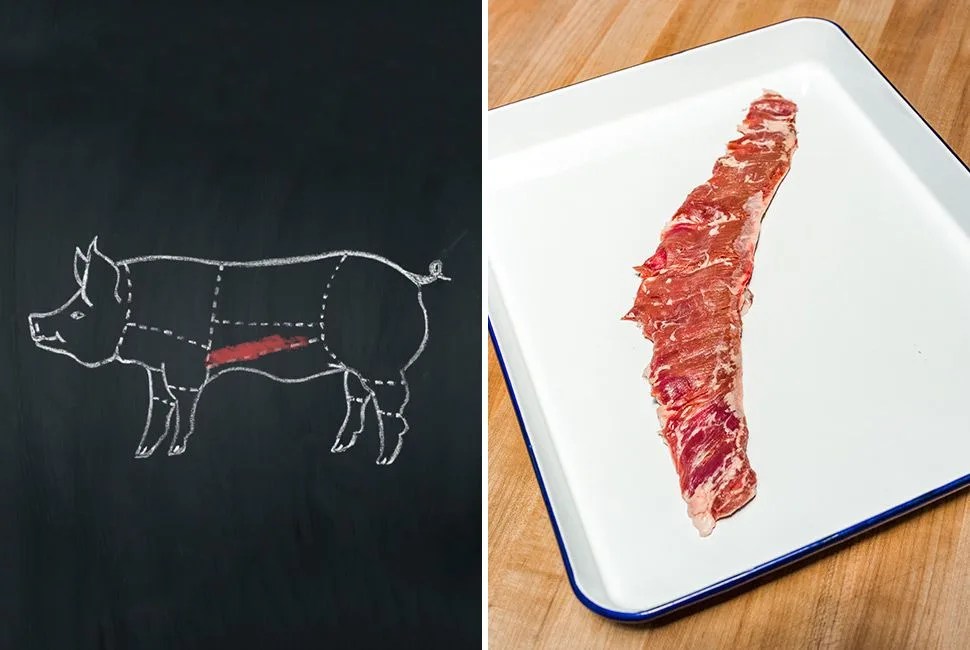

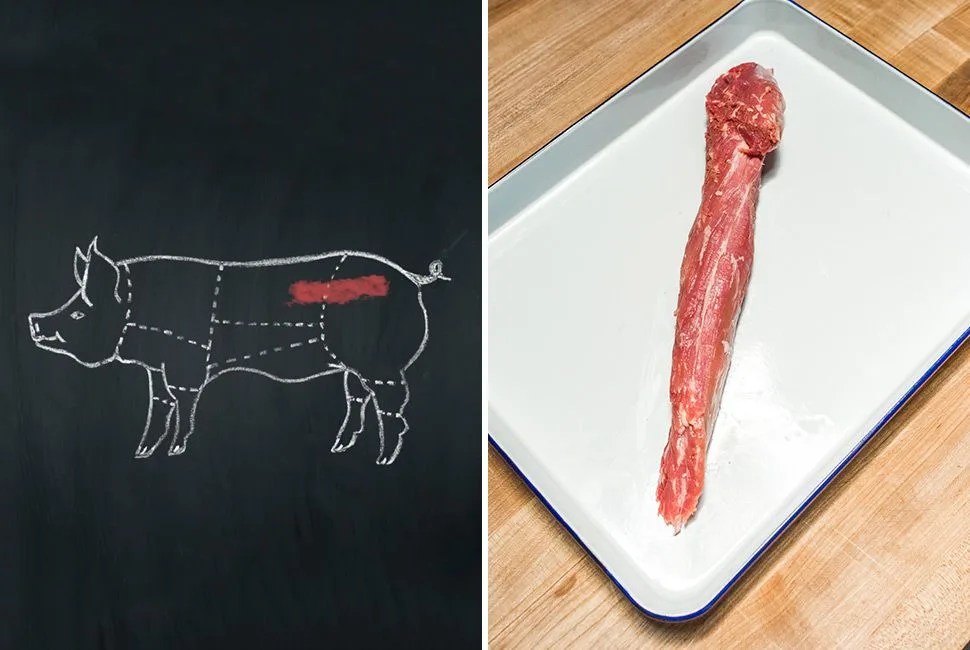

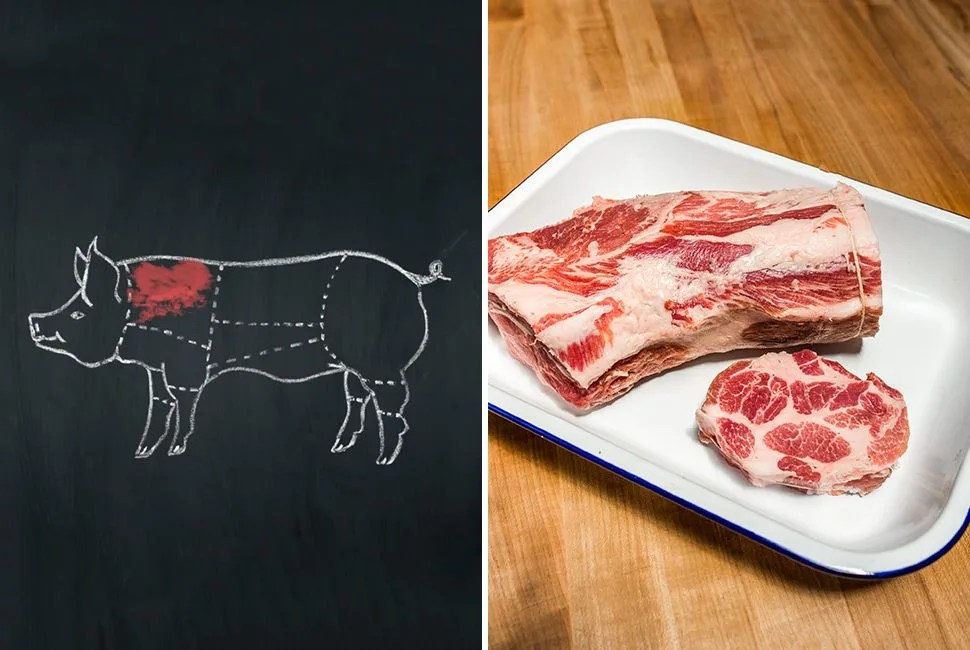

The classes at the Brooklyn Kitchen range from crafting cocktails to learning knife skills to bread making, but today all eyes are on the pig. Since late February, the kitchen has been initiating locals on a kind of backwards engineering of protein. You’ve seen it all before in a restaurant, but given the whole pig, where exactly does the bacon or the country ham come from? Below, find a crash course in everything you wanted to know about pork but were afraid to ask.

Below, we’ve also highlighted some of our favorite pork recipes from across the web. Though several call for specific cuts of pork, we hope you approach them as starting points — mixing and matching different cuts to your tastes, expertise and culinary curiosity. No recipe must be followed to a tee. Collectively, cooking is, and will always be, one long experiment in the pursuit of flavor.

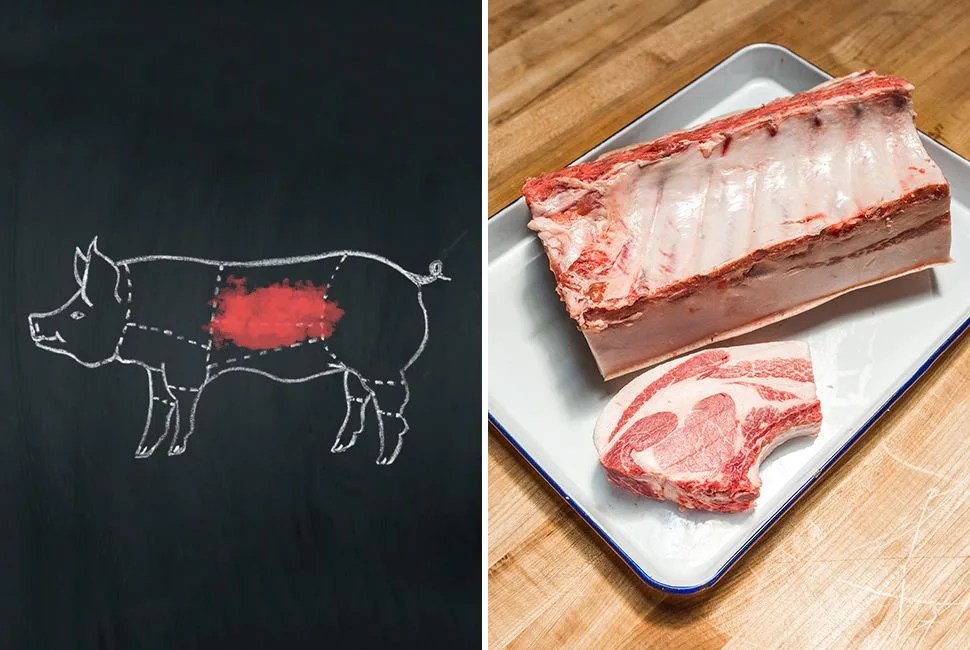

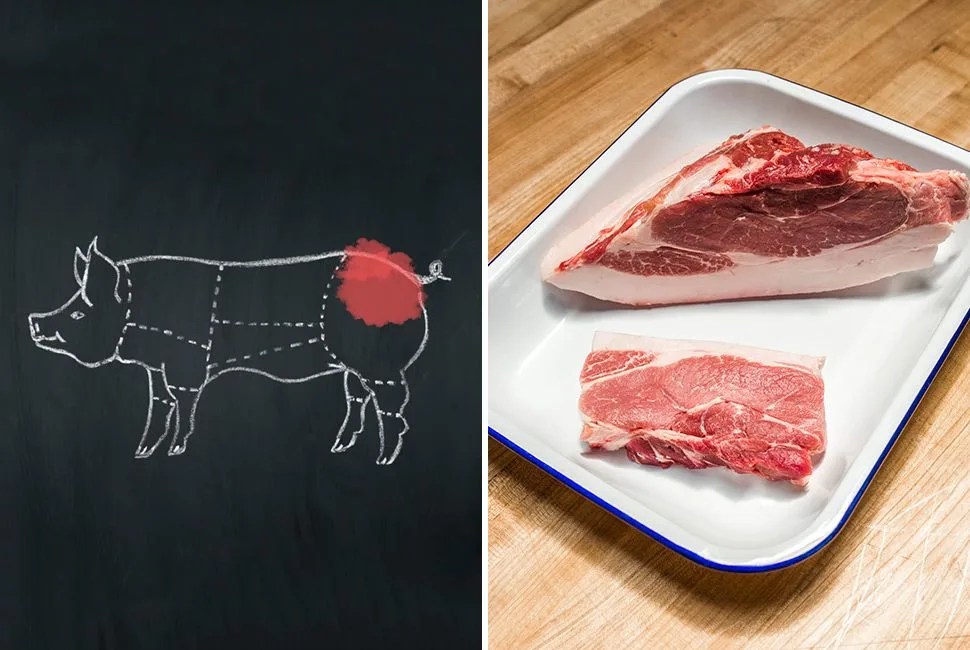

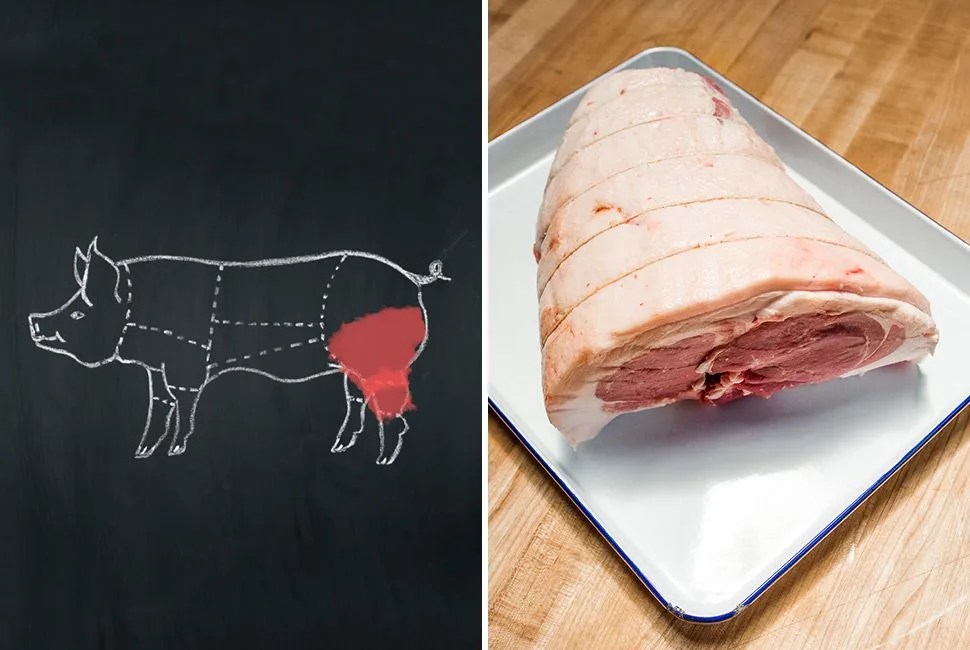

Ham

That juicy ham that sat on the table last Thanksgiving is actually the rear leg, from knee to hip. At the Brooklyn Kitchen, the “house ham” is made by carefully cutting free the skin (and fat) that wraps around the leg and, once a few smaller cuts are removed to shape the ham (which will go into sausage), the skin is rewrapped and tied taut with a slipknot. (The leg from the knee down — the hock — is then used to make broth.)

Cooking: Smoke it slow and low for the juiciest ham.

Alt. Recipe: “Savannah-Country Ham” (Saveur)