7 photos

Despite the ongoing drought that plagues the American West, farms in California and Arizona continue to produce more than 99 percent of the lettuce consumed in the United States. After it is grown, lettuce is harvested and shipped to a central processing facility, where it is cut, washed and treated with a chlorine-containing preservative. It is then sealed in plastic bags, the words “ready to eat” adorned on the wrapper. From there, the lettuce begins its journey across the country, often thousands of miles away, in massive refrigerated trucks or rail cars called “reefers,” leaving huge carbon foot prints in its wake. Chances are, by the time it is consumed, the lettuce is on the tail end of its two- to three-week shelf life.

Unsavory realities like this, which give shape to the greater perception of large-scale industrial farming — a.k.a. Big Agriculture — have begun to sway the purchasing decisions of consumers around the globe. For the past decade, and for a myriad of reasons, buzzwords like “local” and “sustainability” have dominated the global conversation surrounding not just what we eat, but how we’ve come to eat it.

In 2007, the New Oxford American Dictionary named locavore its word of the year, citing “the popularization of a trend in using locally grown ingredients, taking advantage of seasonally available foodstuffs that can be bought and prepared without the need for extra preservatives.”

Around the world, in places like the Middle East, reasons to invest in creative solutions to the local food deficit are often matters of political stability, rather than mitigations of environmental impact. In the Persian Gulf, for example, where an average of 70 percent of the food is imported, the fear is that countries like Saudi Arabia and Kuwait will no longer be able to afford to import food if gas prices continue to fall.

Closer to home, the motivations to eat locally are more personal, dependent on many Americans’ desire for produce that is fresh and has a low environmental impact as well. In New York City, the local food market is growing at a rate of about 24 percent annually (compared to organic, whose growth is less than half that).

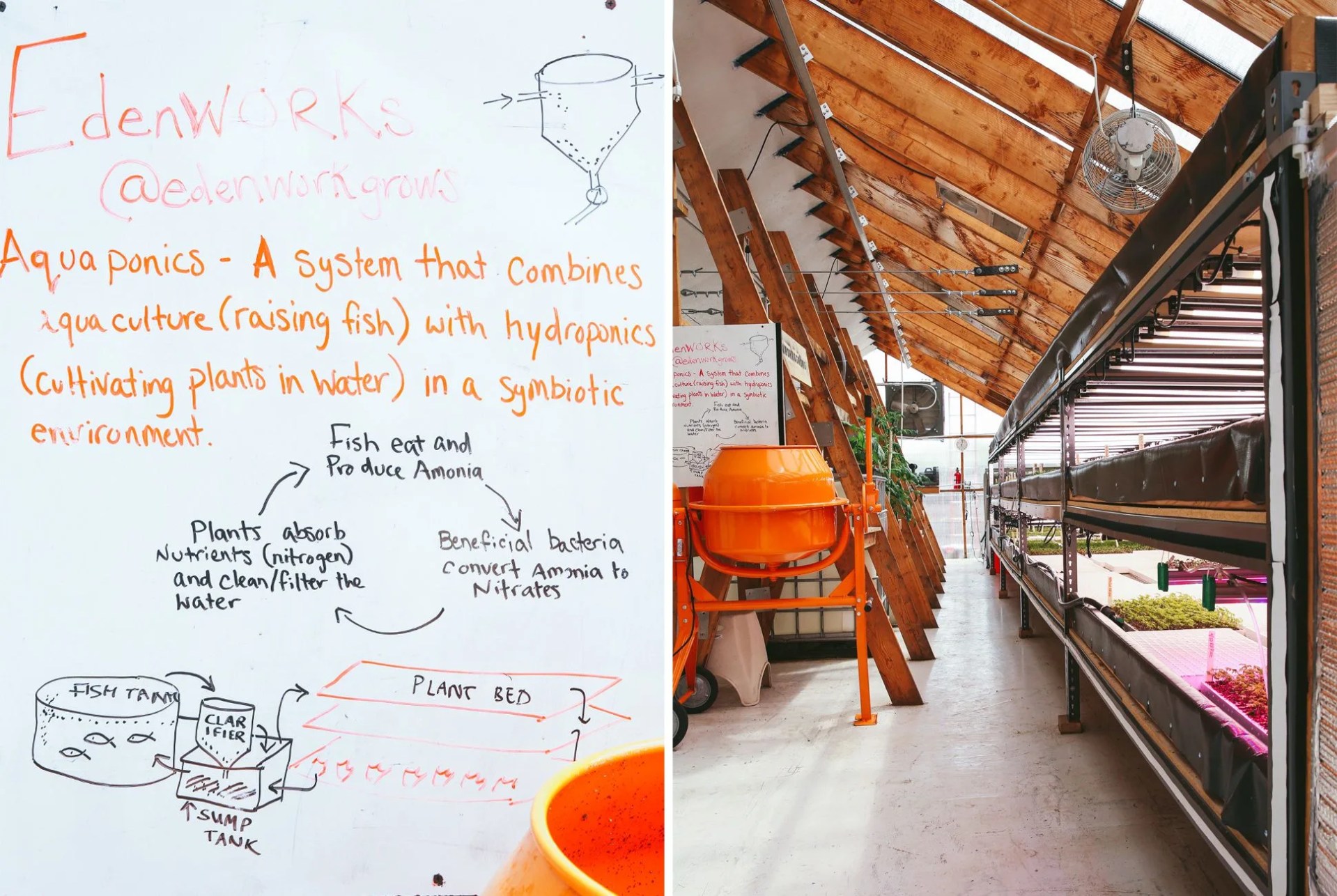

The problem, says Jason Green, founder of the Brooklyn-based urban farming startup Edenworks, is that there’s simply not enough local supply to meet demand. “It’s not like there are twenty-four percent more farms every year,” he says. “How do you sustain that demand?”