From Issue Two of the Gear Patrol Magazine. Subscribe today for 15% off the GP Store.

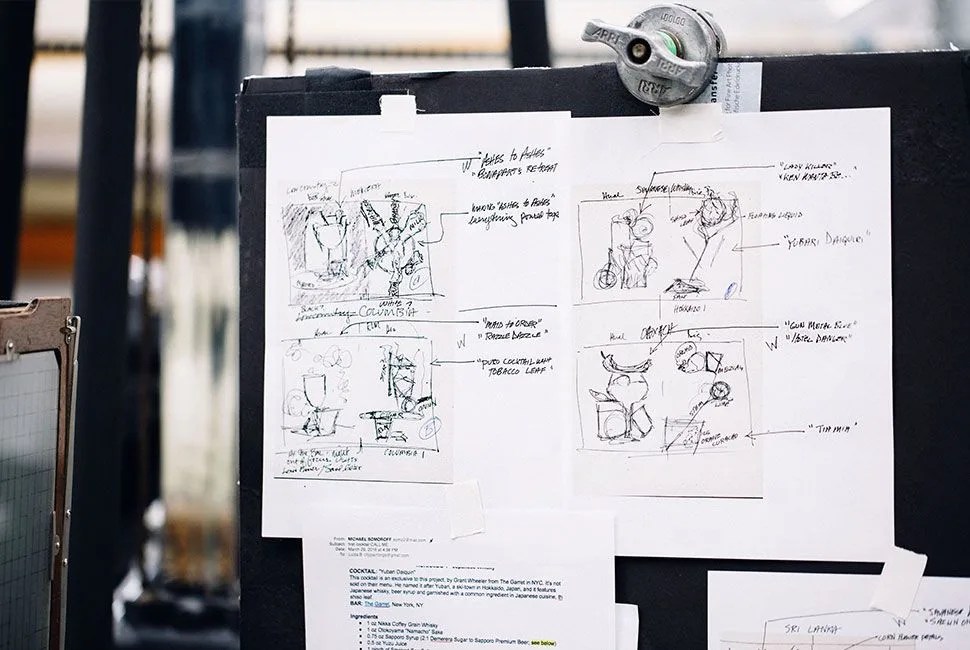

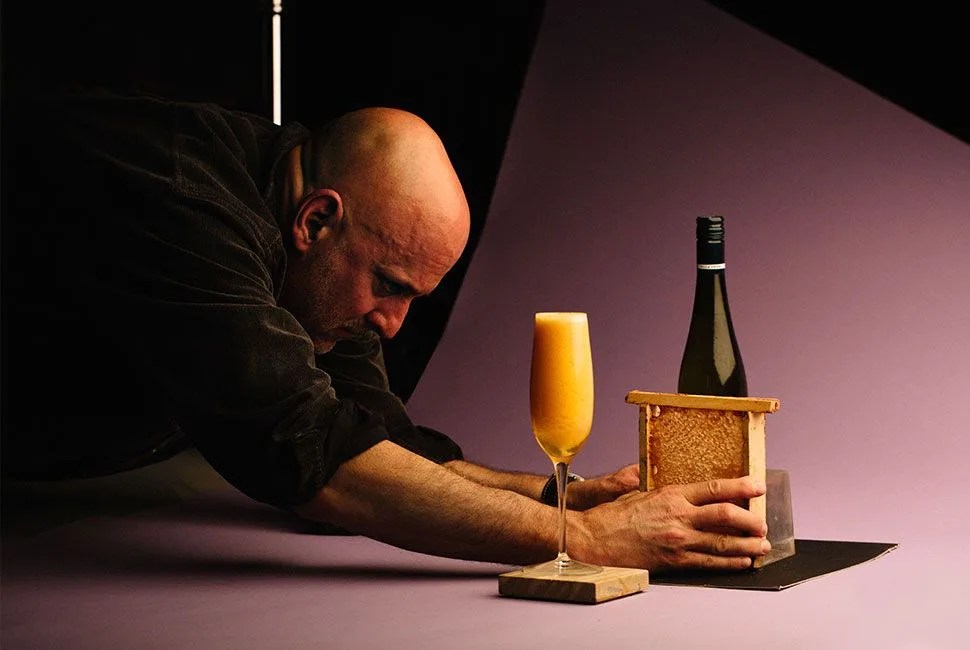

We knew we wanted to have cocktails in Issue Two of the Gear Patrol Magazine, but that presented a problem: Should GP, a publication that lives at the intersection of products and lifestyle, do cocktails the same way everyone else does, i.e., with a recipe and a nice photo? That doesn’t really live up to the “gear” in our name, we felt. So we decided to work with Michael Somoroff, who is a director, photographer, artist and total gearhead (cameras, vintage Jaguars, audio gear, the list goes on). We tasked him with bringing his technical mastery of the craft of photography to the shoot, employing tools and techniques rarely used since the 1950s and ’60s.

Somoroff also happens to be at an interesting place in his career, having just started a joint venture with Imaginary Forces, Somoroff+IF, which collectively harnesses a great deal of experience that ranges from their Hollywood title sequences to art installations he’s done for the Venice Biennale. That opened a lot of doors for us in working on this project (which, by the way, you can see online along with the recipes), which was ultimately produced using a really incredible collection of resources, including a Deardorff 8×10 camera, a Nikon D800, and computer graphics software, to say nothing of the props and lighting. We spoke with Somoroff about the project, and in this interview he offers insight into his deliberation and the technical feats that made it possible.

5 photos

Q: Your background and the craft you learned from your father was a central narrative to this story. Can you talk about that?

A: I was very privileged to grow up in my father’s studio. He came to New York together with another photographer named Louis Faurer and with Ben Rose. He was a student of Alexey Brodovitch who, at the time, was the designer director for Harper’s Bazaar. Some of the other photographers associated with that class were Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, Arnold Newman. Everybody knew each other. Louis met Robert Frank and soon after they became friends; the whole industry grew out this very special community.

In New York, they would all continue the class as a laboratory at somebody’s studio. They would meet regularly and critique each other’s work together with Brodovitch’s supervision. Practically every great name in terms of designers, photographers, visual people of the “Mad men” era, of the ’50s and ’60s, came out of that group. Frank Zachary. Henry Wolf. Milton Glaser. Lou Dorfsman. Herb Lubalin. This was really a very special moment, and I was a kid in that studio wandering through those friendships and affiliations. I worked in the studio. I became my father’s assistant and eventually a studio manager. The studio was a hub. It was an open door policy. On any given day, when lunch was served, you could bump into Milton Glaser sitting next to Howard Zieff sitting next to Melvin Sokolsky. These were giant names of the era. I had the privilege to be apart of all of that.

Q: We looked at your father’s contact sheets from Esquire as inspiration for this shoot. How did your father Ben end up shooting for that magazine?

A: One very special relationship of that time was with a great designer, art director named Henry Wolf, a student of Brodovitch, who went on to become the art director of Esquire in the ’50s before he replaced Brodovitch at Harper’s Bazaar. My father and Henry became very close friends. In those days, Esquire used to have the “Drink of the Month” section. My father used to shoot the cocktails, which he and Henry became famous for. I grew up assisting my father on those assignments later on in the ’60s. They hold a very special place in my heart. In some ways, they really were the cutting edge of still-life photography that he was doing at the time because he was inventing all kinds of things.