From Issue One of the Gear Patrol Magazine. Free shipping for new subscribers.

At 9:23 on a warm winter morning, Rodolfo Guzmán pulls into Boragó, the celebrated restaurant he opened nine years ago in the leafy Vitacura neighborhood of Santiago de Chile. He’s late. “You know, the traffic in this city…” he says, stepping out of his gray Subaru, the thought trailing off into embarrassment. Despite a frazzled air, the 37-year-old Guzmán is naturally handsome: taller than most Chileans, with fair skin and freckles that dot both sides of his unshaven face.

He explains that he’s in the middle of moving houses. “It’s fucking terrible,” he says. “Maybe I don’t look like a mess, but I feel like one, you know.” He leads me up an outdoor staircase, removing a faded baseball cap to reveal his head of bushy brown hair. We pass through the heavy door and I get my first look at Boragó’s test kitchen, which Guzmán has agreed over email to show me “inside and out.”

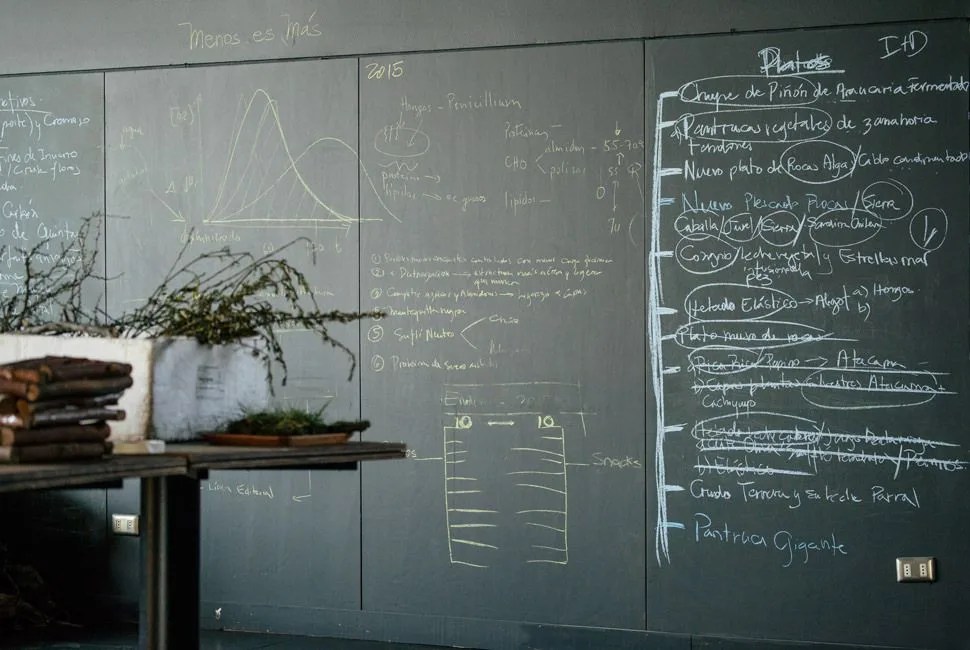

The walls here, painted black, are covered with chalk. They chart the night’s 18-course tasting menu, along with a step-by-step preparation of Guzmán’s latest creation: a carrot infused with live cultures that “melts in your mouth like Camembert and is the craziest fucking texture” he’s ever tasted. The words menos es más — “less is more” — are scribbled at the top of a large wave diagram near the ceiling. Guzmán escapes downstairs for coffee, leaving me alone to wander. By the window, a bookshelf is lined with culinary titans — Redzepi, Andoni, Adrià. Below them are boxes of ingredients labeled with names I don’t understand: “Conchas Picorocos,” “Rica Rica.” From the far end of the room, it all looks like the makings of one big science fair project. Guzmán returns to find me nose deep in a bowl of wet moss.

4 photos

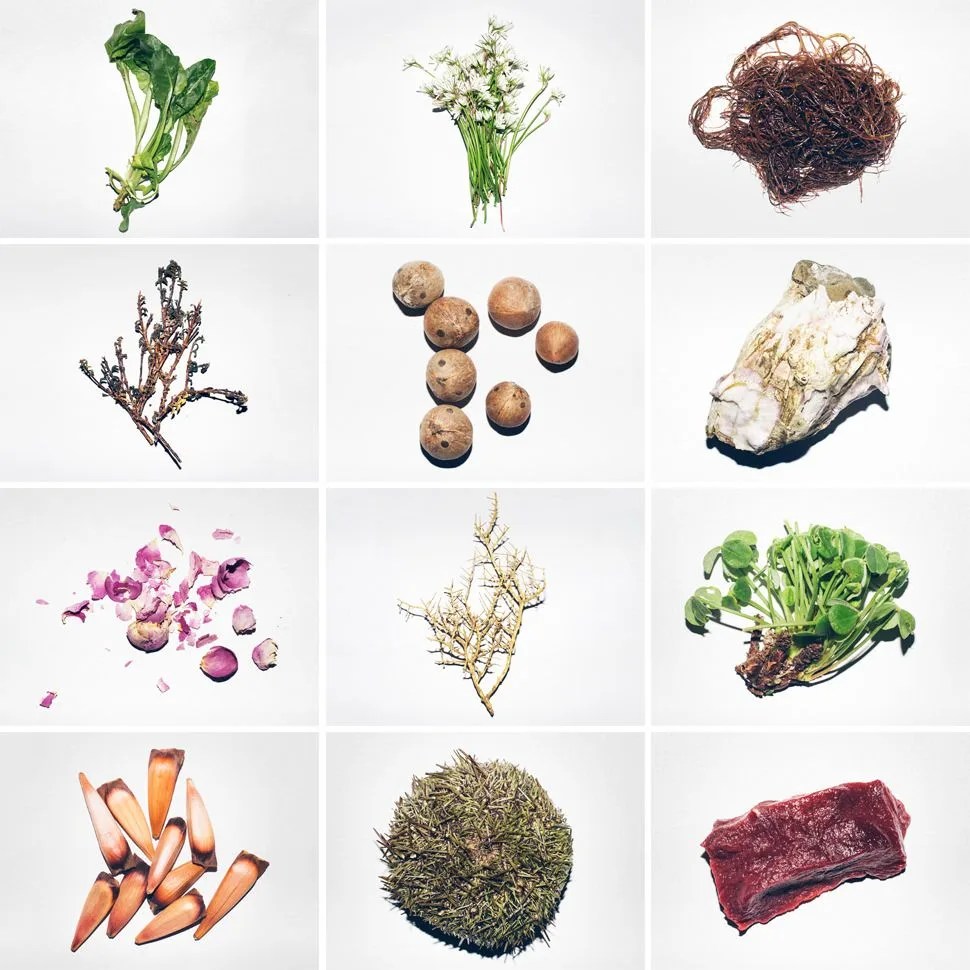

At the helm of Boragó — which is currently number two on the San Pellegrino list of Latin America’s 50 Best Restaurants (ahead of stalwarts Astrid y Gastón in Lima and D.O.M. in São Paulo) — Guzmán has become somewhat of a gastronomic celebrity, a title he shuns with predisposed humility. “I’m just a cook,” he says, albeit one who’s doing something very different in the eyes of the Chilean public. He describes Boragó as “a continuation of the Mapuches,” the country’s indigenous people whose culture dates back to 600 BC. The key to channeling a native identity, and the reason behind Guzmán’s newfound notoriety, is his steady conviction in the discovery of Chile’s vast endemic pantry. “We have ingredients that are very unique in the world,” he says. “We’ve found things in the mountains that only last for two or three weeks a year before they’re gone — the same in the forest or on the coast.” Boragó’s mission is to put them on a plate.

In addition to the kitchen, Boragó’s team has grown into a network of some 200 foragers and biologists across the country who help identify and source a growing index of Chile’s native produce.

Guzmán and I begin our tour of the restaurant, paradoxically, with an hour drive to Isla Negra to forage on the beach — a ritual he and his team must perform several times a week. In addition to the kitchen, Boragó’s team has grown into a network of some 200 foragers and biologists across the country who help identify and source a growing index of Chile’s native produce. (Guzmán needs the manpower: last year, the restaurant served almost 700 different preparations, operating on a grand micro-season calendar.) They also collaborate with a biodynamic farm in the nearby town of El Monte, where Guzmán has introduced several of his field discoveries, including sea strawberries that are peeled and a breed of native chicken that lays blue eggs. In 2016, Guzmán plans to publish his findings in a multi-volume series of books and apps called Conectáz, which will categorize the country’s most obscure ingredients along with preferred methods of harvesting and cooking them.

At Isla Negra, Guzmán pulls off to the side of a dirt road checkered with wooden houses. I step out of the car and hear the ocean breaking on the nearby rocks. Guzmán extracts a styrofoam tub from the trunk and takes off down a wet slope toward the sea. “Careful!” he shouts behind his shoulder. We come across pale vegetables with bubbly outgrowth. They’re sea drops, he says. He plucks a handful and tosses them back. I do the same. They pop. “There’s no flavor, no aroma,” says Guzmán. His wide eyes dance with excitement. “It’s just seawater encapsulated into a vegetable. It’s fucking crazy!” As thrilled as he is, however, he’s not interested in taking any back to Santiago.

A little farther on, he spots a patch of white flowers and runs over, his jeans sinking below his hips. Sea stars. I pluck one and eat it. There’s a hint of spring onion before a wave of honey. “They’re amazing!” says Guzmán, who says he’s been waiting all year for them to show up. He plucks them by the base of their stems, making bouquets and stacking them in the tub. There’s a possibility of rain next week, which could wipe them out for another year. “Hopefully they’ll come out again,” he says, “but we learn to adapt ourselves to what we have.” I ask what he plans to do with the flowers and his face lights up with a grin. “It’s a surprise,” he says.

That night, I sit down for my first and only meal at Boragó. Its 18 courses last for two hours, six minutes and 35 seconds. Every table is full, the minimalist decor matched by a soft, yellow lighting. There is no music, no tablecloths, no waiters — only the cooks, including Guzmán, who take turns explaining every dish. These range from quick bite-size “snacks” to larger dishes that encourage pause: one course, a purée of plants hardened into a clay-like rock, slowly softens and breaks apart in a puddle of seaweed broth.

“I’m very in love with my country,” he adds. “We try really hard here for people to get the whole picture.”

My least favorite preparation comes early on: the skin of a piure, which one of the cooks explains is a filter feeding tunicate. It looks like a ball of wet Play-Doh, filled with a bitter orange purée, meant to mellow the piure’s natural and very potent flavor of iodine. It doesn’t. I swallow it without chewing and am glad there is not a second. Fortunately, the next dish arrives quickly — a combination of crab and coarse sea spinaches, Guzmán’s homage to the central coast of Chile.

The hallmark of the night comes just before dessert. Guzmán approaches my table with a familiar grin. “This is when it gets fun,” he says. He presents a plate of conger eel, cooked in honey and coated with sunflower seed juice. On top are the sea stars from the morning, sprinkled like snow.

Taken as a whole, there is little debate that the meal is delicious. But a low-level state of anxiety underscores one’s introduction to Boragó — not wholly unlike taking the first steps into a foreign city. Only here, the emotional amalgam of excitement, uncertainty and surprise unfolds over an 18-course sequence of bold, unfamiliar flavors. When I ask Guzmán how he expects the average eater to respond, he struggles to find an answer. “It’s about perception,” he says. “We all come from different cultures, different contexts. Everyone feels it differently.” For most, Guzmán’s goal is simply to expose a world that he calls his home. “I’m very in love with my country,” he adds. “We try really hard here for people to get the whole picture.”

9 photos

The next afternoon, I ring the bell to the test kitchen for my final visit. A short man with a mustache and slicked-back hair answers the door. I recognize him from the night before as Koto Sierra, Boragó’s sous chef. He’s noticeably younger than Guzmán, with gauges in his ears. He shakes my hand and I notice his arm is tattooed with produce — red onions, the outlines of mushrooms.

Guzmán is by the stove, dressed in his chef ’s whites with a brown apron tied around his waist. A sharp hissing escapes from a pressure cooker. He tells me they’re working a new dish to debut next week, one made with the deer-like guanaco, sourced from his guy in Patagonia.

The noise gets louder and I see that Sierra is letting out the pressure. Its ceasing leaves only the hushed silence of the room. Guzmán keeps it quiet on purpose. “This is where we study,” he says, pointing to the cookbooks on the shelf. “The test kitchen is a place of learning. Not just for us two, but the whole kitchen — the stagiaires, the line cooks.”

“The test kitchen is a place of learning. Not just for us two, but the whole kitchen — the stagiaires, the line cooks.”

Sierra tells Guzmán that he’s ready to plate the guanaco and removes a piece of meat from the pressure cooker. The broth inside has reduced to a thick, gravy-like consistency. There are remnants of carrots and onions swimming about. It smells like a hearty stew, the kind of familiar peasant fare recognized in every culture around the world.

Guzmán opens a plastic container with a black syrup made from Patagonian maqui berries and proceeds to coat the meat. He’s trying to treat the dish like a dessert; he’s had this idea since January, but has been waiting for the cherry blossoms that color Chile’s central valley every spring. Both men use tweezers to carefully place the flowers, which are sourced from nearby almond and plum trees around Santiago. A final dollop of almond puree (meant to mimic the taste of Chilean kefir, yogurt de pajarito) is added on top.

Then the the two men tear it apart — first with wooden spoons and then their fingers. Each bite changes the proportions of the components. More meat. More syrup. Guzmán uses a squeeze bottle to add the almond puree between his thumb and index finger, licking it off with his eyes closed. They mumble with a hurried intensity: “The guanaco has to be richer.” “Smoked? What do you think?” “There’s too much sugar.” “We need more acidity, more almonds, more bitterness.” “More flowers, more flowers!” Guzmán takes a handful of cherry blossoms and splashes them down on the guanaco. The whole scene unfolds in under a minute. By the end, there’s just an empty plate with streaks of syrup and a couple stray petals.

Sierra retreats first, leaving Guzmán by himself to ponder. The dish is not perfect. And during its short two-week run on the menu — which will last only as long as the cherry blossoms — it never will be. Guzmán knows this. But he also doesn’t care. There’s something here, his wide eyes suggest. And it’s worth sharing.

FROM THE MAGAZINE

This story first appeared in Issue One of the Gear Patrol Magazine, 280 pages of stories, reports, interviews and original photography from seven distinct locations around the world. Subscribe now and receive free shipping on the biannual magazine. Offer expires soon.