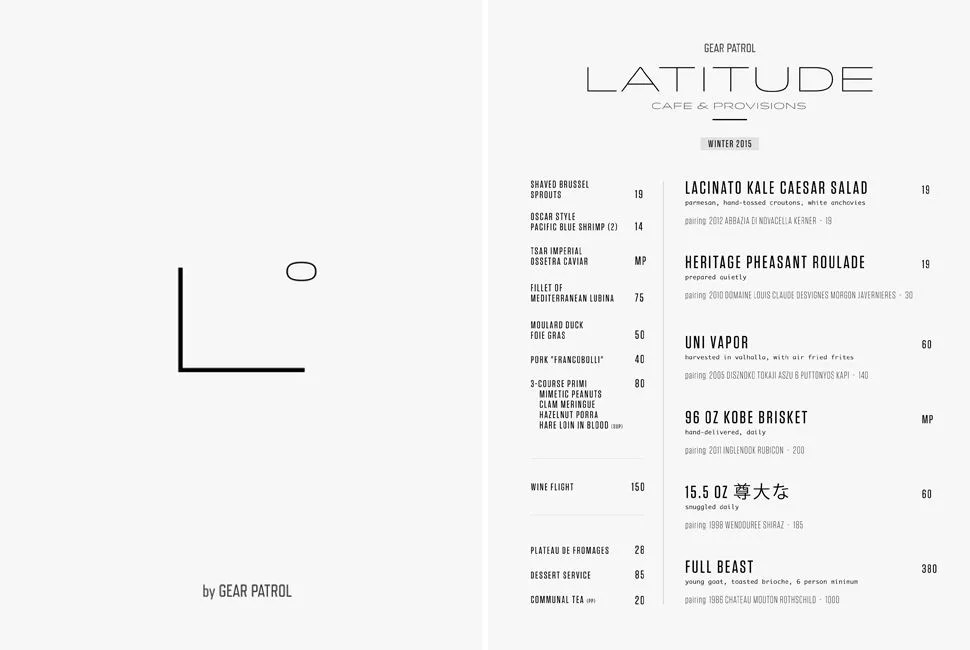

This is a manifesto for simple menus: let your food be inspired and your verbosity chopped. We savor a menu with concise, precise words. We value transparency over fluff. We want menus that tell us what we’re getting without overwhelming, confusing, or deceiving. We want food to be described, not embellished. Let the dish do the talking — keep your menu-mouth shut.

MORE FOOD: Scotland’s Hunter-Gatherer | To the Field for a Pheasant Dinner | 21 Days of Paleo

The past few years, I’ve lived in the two best food cities in the US — New York and San Francisco — and before that I ate my way through three serious contenders: Chicago, Seattle and Los Angeles. I’m a equal-opportunity diner, and I’ve been handed menus at both the $$$ and the $ digs. I’ve lamented overt source-boasting by the high-end spots. I’ve debated how to best describe a dish with chef friends. I’ve suffered description diarrhea at the low-end spots — that never-ending endorsement of a restaurant’s own food. And I’ve had enough. The menu’s become a soap box, preaching the chef’s (or corporation’s) gospel, and it’s time to tone down the evangelism.

The menu’s become a soap box, preaching the chef’s (or corporation’s) gospel. It’s time to tone down the evangelism.

Granted, this can be tricky. High-end restaurateurs are using the menu to provide eaters with information on the source and preparation of expensive food. Where the food comes from (Mary’s Organic chicken), what it was fed (grass-fed beef), and how it’s prepared (slow-roasted tomatoes) makes a difference. On the other side, low-priced eateries have to convince diners that certain foods meet certain standards — and in the world of American processed foods, this matters more than we think. Real Mashed Potatoes are a world apart from Instant Potatoes, no matter how opaque “real” is. Still, let’s call a spade a spade — there’s verbal-menu-vomit all over the place. And it’s time to clean up our act.

Where the Menu Stands, Linguistically

Dan Jurafsky, a Stanford linguist and computer scientist, is a nerd/foodie double threat. He took his complex language programming and studied 6,500 menus and 650,000 menu items, then compiled his findings on menu jargon in the first chapter of his book, The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu. Jurafsky draws three main conclusions: more expensive restaurants leave the diner fewer individual choices (that prix fix), longer words in food descriptions lead to higher prices (your buckwheat orecchiette is costing you), and “linguistic fillers” correlate to lower-priced food (all that “fresh, crisp” lettuce drops the $’s).

All the gaufrette (wafers) and cipollini (onion) on a menu will increase the price 18 cents per additional letter per word.